Clipboard

RACE WATCH

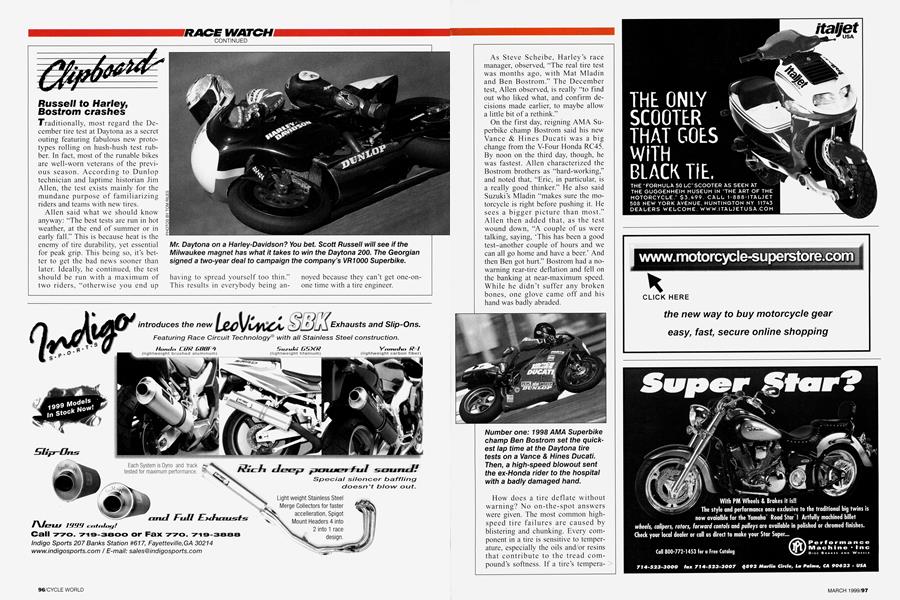

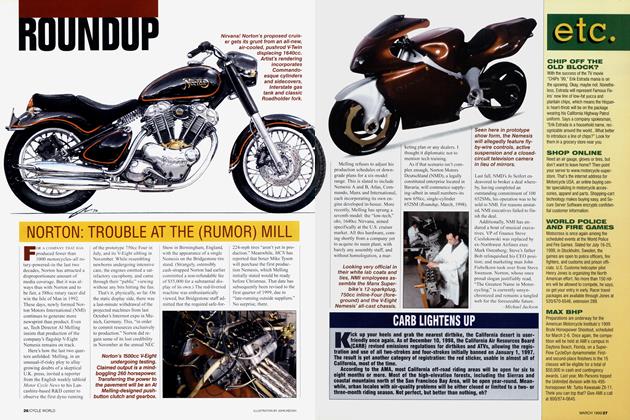

Russell to Harley, Bostrom crashes

Traditionally, most regard the December tire test at Daytona as a secret outing featuring fabulous new prototypes rolling on hush-hush test rubber. In fact, most of the runable bikes are well-worn veterans of the previous season. According to Dunlop technician and laptime historian Jim Allen, the test exists mainly for the mundane purpose of familiarizing riders and teams with new tires.

Allen said what we should know anyway: "The best tests are run in hot weather, at the end of summer or in early fall." This is because heat is the enemy of tire durability, yet essential for peak grip. This being so, it's better to get the bad news sooner than later. Ideally, he continued, the test should be run with a maximum of two riders, "otherwise you end up

having to spread yourself too thin." This results in everybody being an-

noyed because they can't get one-on one time with a tire engineer.

As Steve Scheibe, Harley's race manager, observed, "The real tire test was months ago, with Mat Mladin and Ben Bostrom." The December test, Allen observed, is really "to find out who liked what, and confirm de cisions made earlier, to maybe allow a little bit of a rethink."

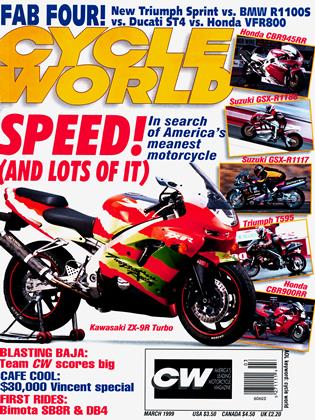

On the first day, reigning AMA Su perbike champ Bostrom said his new Vance & Hines Ducati was a big change from the V-Four Honda RC45. By noon on the third day, though, he was fastest. Allen characterized the Bostrom brothers as "hard-working," and noted that, "Eric, in particular, is a really good thinker." He also said Suzuki's Mladin "makes sure the mo torcycle is right before pushing it. He sees a bigger picture than most." Allen then added that, as the test wound down, "A couple of us were talking, saying, `This has been a good test-another couple of hours and we can all go home and have a beer.' And then Ben got hurt." Bostrom had a no warning rear-tire deflation and fell on the banking at near-maximum speed. While he didn't suffer any broken bones, one glove came off and his hand was badly abraded.

How does a tire deflate without warning? No on-the-spot answers were given. The most common high speed tire failures are caused by blistering and chunking. Every com ponent in a tire is sensitive to temper ature, especially the oils and/or resins that contribute to the tread com pound's softness. If a tire's temperature volatilizes one of these components, the region in question can expand into foam, and material may be thrown from the tire.

This chunking is the centrifugal detachment of large pieces of tread rubber from the tire. It's caused by heat failure of the adhesive bond between the tread rubber and the fiber-reinforced carcass. Often, this process is accompanied by abnormal and increasing vibration, warning the rider to slow down to avoid a failure.

All experienced race personnel have seen blistered or chunked tires, but sudden deflation is highly unusual because of the great durability of modern tire carcasses. In overpressure tests, conducted at many times the normal inflation pressure, failure results when the rim flange breaks or when the tire beads climb over the flange. A few cases also exist in which tubeless tires have gone flat at speed from violent shaking as a result of weave instability.

Five-time Daytona 200 winner

Scott Russell signed with HarleyDavidson on the afternoon of the first day. He knows how to make machines and tires go 200 miles-a special art. Harley has the job of making its VR1000 capable of running strings of laps near Pascal Picotte's fabulous last-year qualifying time of 1:49.265. If the machine cannot run competitive times, Russell's Daytona magic is powerless.

Why didn't 1993 World Superbike champ Russell make the grade on the Suzuki in Grand Prix and, more recently, with Yamaha in World Superbike? As we've seen again and again, some men just find Europe and a foreign team too much to think about, and they lose their way. Mike Hale, who did everything perfectly here in the U.S., yet struggled with Ducati and Suzuki in World Superbike, is another example. A change to new or familiar surroundings can sometimes "reset" a rider's career. We can hope that being stateside, surrounded by English-speakers who know what "Dayyum" means, will do the trick for Russell.

Could it be true that "you can't win with a Twin" at Daytona? It's obvious from years of results that you can win anywhere else with one, so sustained high-rpm reliability has to be the issue. I suspect the problem, if any, is not so much two cylinders as it is that Ducatis have been developed for Eu ropean events with their constantly varying rpm. The Japanese compa nies, by contrast, have for years put great effort into attaining specific Daytona reliability. The necessary testing may embed a lot of parts in dyno room ceilings and walls, but when a Twin is developed in the same way, it will be able to win Daytona.

Scheibe revealed that Harley will make an increased financial commit ment to the VR for two years. To my question about what's new, he replied only that they are evaluating several new things that aren't yet properly integrated. He denied the obvious accusation, that Russell was hired to win Daytona. Rather, the team wants access to the Georgian's expectations of how a machine should handle. Until proven otherwise, then, we shall disregard suggestions by skeptics that Harley is to be Russell's "retirement home." Let's hope that somewhere, rows of freshly installed dyno cells are reverberating with repeated, multi-hour, full-throttle tests.

At one point, a VR1000 and Eric Bostrom's Honda CBR600F4 Supersport bike were running close together around the banking. "There wasn't much in it," was an onlooker's observation of the Harley. Everyone would like to see The Motor Company do well or, as one team manager carefully put it, "to win one race."

New on the Harley is a Showa fork, which Scheibe said both Picotte and Russell found to be, "a slide-out, slide-in improvement, with no adjustment." Another is that data pack and engine controls are now both supplied by Marelli. The engine is mechanically safe to 13,000 rpm. Now, they just have to make power and hook it up the way it worked for Picotte on that one super lap.

Is Kawasaki being left behind by changes in racing? For years, many believed that race winners don't win titles; titles are won with steady seconds and thirds. Doug Chandler's combination of safe, predictable handling setups and craftsman-like riding has indeed won titles. But now, young hotshots on bikes set up to hook up rather than smoothly spin-steer are winning more often.

With the advances in suspension and tires, horsepower has returned to semi-respectability. Chandler didn't appear at this test, with contract issues cited as cause of his absence. He'll return on the Superbike, but will not contest 600 Supersport. Would he like a fourth title? Will something new be required to achieve it? Aaron Yates, who left Suzuki for Kawasaki, used the test mainly to familiarize himself with the Muzzy ZX-7R.

Was the test a race preview? Probably not, because not all riders adapt to new machines as quickly as Ben Bostrom, not all the new machines were present (no Yamaha YZF-R7, for example), and the newer the equipment (Harley's Showa stuff and other changes), the less likely it was to be at its best. All in a day's work.

-Kevin Cameron

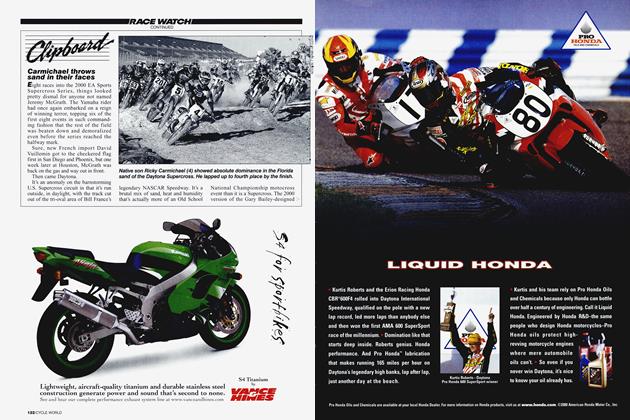

Motocross musical chairs

Virtually all the rumor mongering and muckraking surrounding motocross' "silly season" swirled around Yamaha. What initiated the frenzied seatswitching was Jeremy McGrath's planned "Supercross-only" racing contract. After winning five indoor titles, the beloved king of stadium racing elected to hammer out an unprecedented contract that will see him race only Supercross in 1999 (along with four hand-picked outdoor Nationals).

The resulting contract sent team managers and riders scrambling for support. Realizing that it would need a strong teammate to ride as a tailgunner for McGrath in the klieg-lit Supercross ball yards, not to mention make a run at the AMA 250cc National Championship, Chaparral hired longtime Honda pilot Steve Lamson.

Meanwhile, due to an alleged personality conflict within the Yamaha race team, Kevin Windham decided to leave for Honda. With his rushed departure, Windham was caught in the middle of a legal firestorm-much

of it revolving around the 1999 YZ print campaign in which he is featured. This had higher-ups at both manufacturers circling the legal war wagons. As of mid-December, the situation had yet to be sorted out. It does appear, however, that Windham will be a Red Rider in '99.

Yamaha's headaches didn't end there. After winning the 1998 AMA 250cc National Championship aboard the thundering YZ400F, Doug Henry informed company officials that he was considering retirement. Wildly popular with fans for his never-saydie attitude (not to mention his brave fight back from a litany of careerthreatening crashes), the war-weary Henry was keen to spend more time with his wife and children. Besides,

there was another racing goal that intrigued him.

"I'm going to do some snowmobile racing this winter," said Henry. "It's something I've always wanted to do.

For the past couple of years, I've just been riding so much that during the middle of this season, I knew I need ed to look at something else. I've been a snowmobile fan for a long time and have wanted to race them, and decided I wasn't ready to do a full season (of Supercross) in 1999. So what I am going to do is race Snocross this winter."

Henry added that he plans to com pete in the Daytona Supercross in early March before making a possible assault on the outdoor 1999 AMA 250cc National Championship Series.

iiTic~ i~;'~T Yamaha was left without a racer to ride and promote its YZ400F. With only John Dowd signed to a factory contract for the 1999 season, Yamaha invited Jimmy Button and Mike Brown to an ad-hoc, man-against man tryout for the coveted four-stroke ride. When the fight was over and the dust had settled, Button signed a fac tory contract to ride the growling beast in both AMA stadium and out door campaigns. -Eric Johnson

World Superbike looks to lower costs

World Superbike is attracting ever re attention because it is a hardfought and dramatic series in which any one of several fine riders is capa ble of winning. NASCAR fans make much of the race-what-you-sell as pect of WSB, but to most spectators, motorcycles in fairings look alike re gardless of their propulsion.

Growing from informal and rather club-like beginnings, WSB has gar nered factory interest by degrees until in 1997, Honda reportedly spent more on WSB than it did on Grand Prix rac ing-perhaps as much as $17 million.

Ducati, in its workmanlike, persis tent way, has established itself as the master, overcoming Kawasaki and forcing Honda to dig deep for its 1997 championship with John Kocin ski. Just as Honda PR types were heaving a multi-media sigh of relief over its title ("Now things are back to normal!"), back came Ducati and sharp-visaged Carl Fogarty to nar rowly retake the crown. Surprise!

It is at this high-spending juncture that we hear of new WSB technical rules, under discussion to take effect in 2001. Billed as a bump for priva teers, it may in fact be a budgetary re prieve for the factory teams.

WSB began as an experimental FIM class, broadly based upon the AMA's experience with productionbased racing here in the U.S. Major castings, such as crankcase and cylinder head, begin life as production articles. The parts could be modified, but any change to the basic castings as starting points requires a new homologation.

Within that framework, manufacturers have created exotic four-stroke machinery of a type quite out of reach for private teams. Indeed, the history of WSB has been one of steadily decreasing privateer participation, as the game has increased in technical sophistication and expense.

In WSB, the "man-in-a-van-with-aplan" no longer exists; the privateer banner is carried only nationally, by distributor-backed teams. Romantics have viewed this as a major drawback to the class, while realists have accepted that strong factory participation is essential for a major racing series. Such infusion of factory resources assures top riders and top equipment.

The contemplated new rules appear at first to address this decline of the privateer. In simplified form, the new rules would limit WSB equipment to the homologated machine, plus a homologated racing kit. This kit could be updated once in the first year of a model's homologation, and twice a year thereafter, with the kit's price limited to $40,000.

No modifications would be permitted to any of these kit parts, and exemplar parts would be carried by the series tech-inspection crew for comparison. Those desiring to do their own development could do so, but only starting with the stock, non-kit parts on the homologated motorcycle.

One way to look at the technical proposals is that without the customary fast pace of development, WSB would become just a higher-level Supersport, played with $40,000 kits instead of with stock motorcycles.

To understand it better, I spoke to Steve Whitelock, who is the WSB tech inspector and a veteran of many years' participation in international racing. "I am having a nightmare thinking how to police this," he said of the kit-parts plan. How can it be guaranteed that the intake ports in a competitor's engine are indeed of the exact same shape as those in the exemplar part?

In the early, more informal days of WSB, there was considerable mutual restraint in technical development. Everyone knew what everyone else was doing, and if one team objected to another's rules interpretation, the affair could often be solved "in consultation." But inevitably, the increased influence of the series upon sales unleashed the customary R&D spending, so WSB has become more GP-like. Honda's attempts to vindicate its slowly developing RC45 became ever more vigorous and Ducati replied as best it could. The result has been some decline of informality.

When asked who supports the rules changes, Whitelock replied, "The Japanese support them wholeheartedly, and Ducati sees an opportunity for their new Ducati Performance organization to sell racing kit parts in quantity, worldwide. The parts can be sold separately, as well as in kits." The Japanese and Italian manufacturers met this fall, but the final decisions will come at the FIM's Spring conference in Geneva.

Now the murk clears: These new restrictions will have the effect of drastically reducing the role of big-money R&D in WSB. That appeals to manufacturers who have spent too much money that is harder to get in a time of financial uncertainty. The series is wonderful advertising, but would continue to be so even if WSB's present "space-race" R&D spending was replaced by rules-regulated development. Privateers might indeed benefit, but their well-being is not the driving force behind these changes.

What are we to make of these rules changes? I see them as a part of the trend-visible in all forms of motor racing-toward making the sport more game-like by increasingly defining everything that may and may not be done.

Racing equipment is becoming a multiple-choice test or a kind of Lego toy set. For those of us who relish unlimited technical developments, this is deplorable. But teams go home when racing becomes too expensive-as the British teams did in 1954, the Italians did in 1958 and the Japanese did in 1968. Everyone wants to avoid that and keep the present, useful-and-exciting show going.

Besides, the real meat of motorcycleracing development is not shrieking, roaring engines. It is the silent subtlety of the chassis, that complex instrument that no one really plays well. May the best instrumentalists win.

-Kevin Cameron

U.S. goes down (under) in 73rd ISDE

Off-road racing teaches one to adapt, to be ready for any conditions, but rarely have racers had to face the variations thrown at them in the 73rd International Six Days Enduro. Not only did competitors venture to Australia for only the second time in history, but they learned a number of lessons.

For one, the weather in Traralgon (about 100 miles east of Melbourne) is about as predictable as it is in the Midwest: If you don't like it, wait a bit. It started warm and dry, leading all to believe that this would be one of the siltiest Six Days in recent memory. To adapt, many tried old desert tricks, like oiling the vent foam in their goggles and fitting a second air filter over the primary one. That all went out the window on Day Three. An all-night rainstorm-in an area coming out of its second-consecutive dry winter-turned the course into the type of mudfest that enduro riders giggle about, especially those who hail from the East Coast.

Unfortunately, the unexpected deluge acted like a flash flood in some areas. One river crossing was shallow enough for a few dozen riders to cross safely, but after that it got too deep. That left more than 300 others stranded on the near bank, questioning how to continue. The organizers conceded, in an unprecedented act, by canceling the day, nullifying one test because not everyone had a chance to ride it. It was now the International Five Days Enduro.

Continued rain made it impossible for service and safety crews to reach the outer points of Day Four's course, so it became a road ride-which started 4 hours late-with one grass track test run twice. Day Five originally held many difficult climbs, but the

organizers feared those would've been impassable, so they laid out a new course overnight. In all, this Six Days turned out to be almost like two different back-to-back Qualifiers, not that it favored American racers. The fact that Australia's Shane > Watts set overall fast times on a 125 seemed to stun Americans. Five-time Trophy team member Ty Davis, the fastest of the Americans on a Yamaha WR400F, observed, "The big bikes are all doing pretty much the same times, but the 125s seem to have an advantage, and they're kicking our butts."

And at this ISDE, Australia showed it's in a different league, with its Trophy team making tremendous advances in talent-and fortunes-to finish third behind Finland and Sweden. It marked the first time on the box for Oz and only the second time at the top for Finland. That should give America's finest some hope. Of America's ninth-place finish, Trophy team manager Dave Bertram said, "I think they flew the colors well for the States. It was just the way the weather changed, the way the tests developed. I guess the cards just didn't fall in our favor."

-Mark Kariya