Supeer moto!

RACE WATCH

It’s “The Superbikers” all over again at Laguna

KEVIN CAMERON

SUPERMOTO IS A NEW MOTORCYCLE

sport that brings all riding skills to-

gether in one event, on machines al-

read widely available. It includes

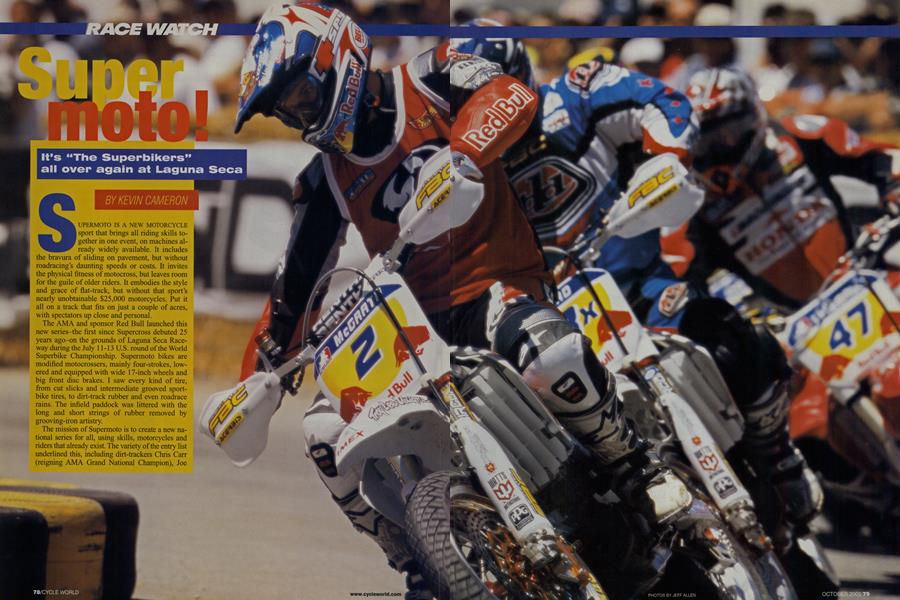

the bravura of sliding on pavement, but without roadracing’s daunting speeds or costs. It invites the physical fitness of motocross, but leaves room for the guile of older riders. It embodies the style and grace of flat-track, but without that sport’s nearly unobtainable $25,000 motorcycles. Put it all on a track that fits on just a couple of acres, with spectators up close and personal.

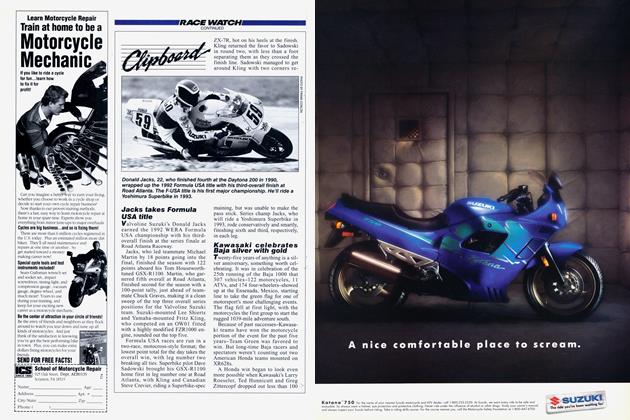

The AMA and sponsor Red Bull launched this new series-the first since Supercross debuted 25 years ago-on the grounds of Laguna Seca Raceway during the July 11-13 U.S. round of the World Superbike Championship. Supermoto bikes are modified motocrossers, mainly four-strokes, lowered and equipped with wide 17-inch wheels and big front disc brakes. I saw every kind of tire, from cut slicks and intermediate grooved sportbike tires, to dirt-track rubber and even roadrace rains. The infield paddock was littered with the long and short strings of rubber removed by grooving-iron artistry.

The mission of Supermoto is to create a new national series for all, using skills, motorcycles and riders that already exist. The variety of the entry list underlined this, including dirt-trackers Chris Carr (reigning AMA Grand National Champion), Joe Kopp (the 2001 champ), Terry Poovey and J.R. Schnabel. Add roadracers Kevin Schwantz (1993 500cc World Champion), Doug Chandler (three-time AMA Superbike champ), Thomas Stevens (1991 AMA Superbike champ), Larry Pegram, Dave Sadowski, Al Salaverria and Mike Smith. Sprinkle in motocrossers Jeff Ward, Jeremy McGrath, Micky Dymond, Danny LaPorte, Jeff atiasevich and Chuck Sun, and aerobatic stylists Mike Metzger and Mike . And finally, foreign Supermoto specialists Kurt Nicoll, Alex Thiebault, Fabien Rolland, Phil Gee and Mark Avard. What does this glittering entry list mean? It means that top riders of all persuasions-both active and “retired”-enjoy this kind of racing and are voting with their presence for its success.

Also remarkable was the unity of outlook expressed by the industry heavies with whom I spoke. They believe the new series will succeed, and liken its simple enthusiasm to the feel of paddocks 20 or more years ago. “It’s like motocross in the ’70s,” more than one onlooker was heard to say. The high status of professional racing today is a gain for all who work within it, but people miss the feeling of community and common purpose of the privateer era. They feel that a fresh beginning like this has some hope of restoring these grass-roots attractions.

The aggressive, tail-sliding “American Style” in Grand Prix roadracing, pioneered by Kenny Roberts and continued by others, originated on U.S. dirt-tracks. Sadly, dirt-track has become increasingly specialized, with fewer riders now crossing over into roadracing. The show at the established dirt-track nationals remains spectacular, but the infrastructure of local events has dried up as the specialized equipment and its maintenance have increased in cost. The AMA has launched at least three major programs to revitalize this sport over the years, but none has reversed the decline at the grass-roots level. Supermoto attempts to stem these losses with a fresh format at all levels. U.S. racing began with dirt-track, then slowly added roadracing. Later, the European sport of motocross was transplanted here and its popularity exploded. All three disciplines have grown apart from each other, requiring beginning riders to choose one and concentrate his skills and resources on it. Instead of the versatile riders of the 1960s-able to compete on mile and half-mile, in TT and roadrace-today’s rider has to pick one and concentrate to the exclusion of the others. Why? Racing is expensive and modem equipment is specialized. In the 1960s, the same basic machine could, with wheel, tire and brake changes, be used in several kinds of events. A manageable investment in equipment, combined with versatile skills, could add up to something like an income. This was the sustaining basis of grassroots racing in America. I knew riders in won money at local tracks times a week.

The growing professionalism of each motorcycle sport has required more specialized equipment, and thus costs more. The growth of factory racing further raised the level. At present, the factory rider earns a decent living, but most others must ride as self-funded amateurs. The Supermoto concept goes back to 1979, to English promoter Gavin Trippe. To get more show from less investment, he conceived the combining of all riding disciplines into a single activity. This drew upon the maximum number of possible riders to create an IROC-style event appealing to all persuasions of spectator. The result was ABC Wide World of Sports’ “The Superbikers,” a made-forTV show running on a half-paved, halfdirt track at Carlsbad, California. When that yearly show’s ratings began to tail off circa 1985, the concept went subterranean, to surface in the ’90s in Europe as Supermotard. Soon, Americans readopted the sport, Cycle World's own Don Canet going so far as to start his own series, which he dubbed SuperTT.

Now, the AMA plans to place Supermoto (the new, homologated name for this form of racing) events on the programs of its most successful established venues. This “marsupial plan” hopes,

by nurturing the infant Supermoto in the pouch of established events, to expose a large public to it-tens of thousands of fans witnessed the races at Laguna Seca. If Supermoto in time becomes self-sustaining, with events from local level all the way to the top, it might well put back some of the grassroots strength that formerly existed.

The proposed series noise level of 98 decibels and a typical track/spectator area of only a few acres can fit this racing into many places where no other can

exist. Compact size also facilitates TV coverage by a limited number of cameras and crew. Another big plus is the ability to run rain or shine, avoiding the hassles of delays and cancellation should the weather turn soupy.

The Laguna Seca Supermoto track was designed by Canet, working with the AMA as race director of the inaugural six-race series. It was located at one end of the vendors’ area, filled with pedestrian traffic. Approximately 65 percent asphalt and 35 percent dirt, the course was a half-mile long, slightly shorter than usual. As always on dirt, the surface changed during the event-what started out as soft cushion slowly became a blue groove, hard as pavement. Big yellow ag-machines stood by to restore dirt surfaces between races (I thought they might put in a crop of beets), and the lumbering water truck came and went. This kind of racing is very demanding. CW Assistant Editor Mark Cernicky, a SuperTT regular, noted, “If you make just a little mistake, three guys pass you.” The mains are long enough to be demanding, as Kopp remarked, “Those 24 laps felt longer than a mile national!” I stood at a pavement hairpin, watching riders brake and turn. The trick is to enter in a rear-wheel slide that steers the

bike around the first half of the turn, then smoothly feed throttle while easing off the rear brake to make a smooth drive out. This is complicated by the jolt that usually occurs as a sliding tire hooks up. A number of riders, concentrating on their beautiful slides, found themselves almost stopped at the apex, passed by less stylish but more vigilant competitors. Yet the top few could transition with beautiful smoothness from brakes to power, making an unbeatable drive off the turn every lap. I was told that one way to smooth this transition is to set engine idle up around 2500 rpm. Decelerating with the rear brake on, the engine is “invisible,” but releasing the brake allows its power to smoothly take the place of brake torque.

When Nicky Hayden rode a Honda CRF450R in a SuperTT event at Anaheim Stadium last year, he rode the course in two contrasting styles, roadrace and dirt-track. On the stopwatch, the roadrace style was slightly fastertires have peak grip on pavement just before they slide. Yet the slightest mistake, or another rider in the way, would spoil the lap. Riding dirt-track style, with the bike already sliding, mistakes were more manageable and Hayden had more freedom to maneuver. Two classes exist in the AMA series: the premier Red Bull Supermoto class, for 450cc four-strokes, and the Unlimited class, sponsored by KTM, for twoand four-strokes 490cc and larger. A stock KTM 450 SX, for example, makes something like 48 horsepower, while a tuned KTM 660 LC4 might put out as much as 70 bhp. Minimum weight for the Supermoto class is 216 pounds dry (Unlimited is exactly that), so acceleration is quick.

Stopping at the apex on a big fourstroke MX Single is no joke. For the sake of lightness and revability, these en~’~es are built with almost no flywheel mass, so if rpm drops too far, a stall results. I watched one rider after another to restart his engine after such flameOnly the lucky succeeded.

Bikes are at an early stage of development, with manufacturers like KTM,

Yamaha and Honda watching closely to see if a market for a purpose-built Supermoto bike emerges. For now, you start with a big MX bike, lower the suspension an inch or two, set aside the big MX wheels for wide, 17-inch rims, and lever on the tires of your choice.

What is the price of admission? A new Japanese 450cc MXer goes for about $6000, and $2000 will cover wheel, brake and suspension changes. Specialized European bikes cost more, while used equipment brings the numbers down. Of the 98 pre-entries in the Supermoto class at Laguna, 58 were on Hondas, 22 on Yamahas, 13 on KTMs and five on Suzukis. In Unlimited, KTM was dominant with 20 entries; Honda had seven, Vertemati six, Husqvama and Kawasaki two, Husaberg, Suzuki and Yamaha one each. Despite the four-stroke majority, a few two-strokes could be heard.

For the rider, this class appeals becausfe-for the moment at least-skill buys more result than budget. Because speeds are moderate, serious injuries are rare. Equipment is affordable and available. Super-tuning is not required and tracks are designed to fairly balance roadrace, dirt-track and MX skills, give or take. As one competitor put it, “Don’t whine. You got your section where you’ll look good right over there.”

For the spectator, Supermoto puts viewers up close to the action. There is the direct gut appeal of sliding, jumping and constant elbow-to-elbow racing, something that’s missing from roadracing, where insurance stipulations have driven fans far from the hurly-burly, behind rows of catch fences.

For the promoter, there is the compactness of the track and the ease with which this show can be combined with others, already established. For TV, small size scores again-dozens of cameras and miles of coax aren’t events. Already, some are talking about putting Supermoto into stadiums, into the X-Games, or combining it with monster trucks. Already, the premier event in French Supermotard racing, the Guidon d Or, takes place inside Bercy Stadium.

AMA’s head of Pro Racing, Scott Hollingsworth, says that the plan calls for sheltering the class-“Bringing the race to the spectator”-as part of other events while interest grows. The enthusiasm of Pro riders from other disciplines is a gift. Even if not permanent, the presence of top riders adds interest that can only help.

KTM Motorsports Marketing Manager Ron Heben said, “Right now, this is sort of a retired star rider’s class; a retired Pro can afford a couple of bikes and spare wheels. As long as he can win, he’ll be here, he’s happy. But he doesn’t want to be beat by some 16-year-old.”

Racing classes can’t be permanent because circumstances change. Therefore, a sanctioning body must treat them as a gardener treats plants. To ensure a good harvest, many seeds must be planted. Those that grow are cultivated. Those past maturity are pulled to allow new growth. The Sportster 883 roadrace class in its heyday brought Harley dealers back to the races and trained future top riders such as the Bostrom brothers.

When entries faded after a few years, the class was replaced.

Even successful classes may not develop as planned, but the result can still be good. Battle of the Twins was designed as a haven for obsolete British iron, but evolved into the world’s only four-stroke GP class, attracting such innovative creations as Don Tilley’s “Lucifer’s Hammer,” the late John Britten’s VI000 and the exotic Quantel Cosworth. When it eventually devolved into a single-brand show, its time was up. Supermoto’s elements of available equipment, non-specialized riding style and moderate costs could lead future racing in many directions.

Why should fans of the established riding disciplines add Supermoto to their interests? First of all, they just might like it. Spectators at Laguna did, crowding up

to the perimeter fence fourand fivedeep. And riders like it, too, as shown by the Laguna entry list; they weren’t there for the money, either, as the purse was a paltry $3000 until custom-helmet impresario Troy Lee pitched in a few thousand more. But most important is the old truism that, “A motorcycle is a motorcycle.” If you can ride one style well, chances are good you can ride others. Supermoto makes it happen. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Last Harley

October 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRevenge of the Soccer Dads

October 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCClutch Players

October 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2003 -

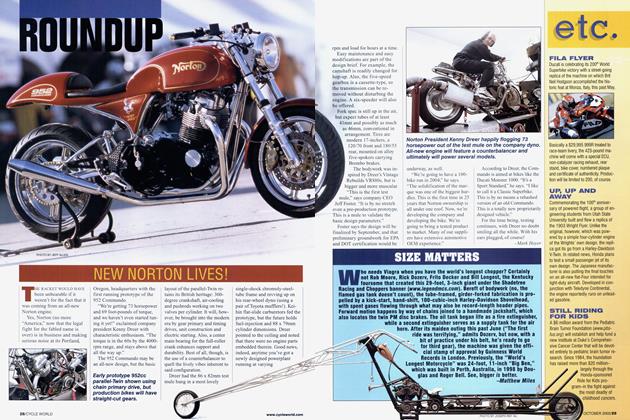

Roundup

RoundupNew Norton Lives!

October 2003 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupSize Matters

October 2003 By Matthew Miles