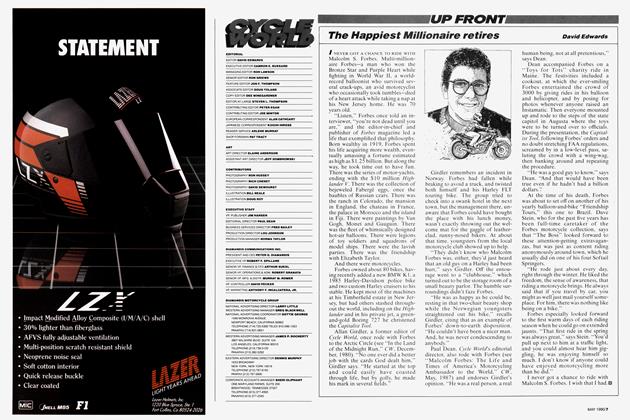

The Last Harley

UP FRONT

David Edwards

ONLY IN AMERICA COULD HARLEYDavidson have happened.

Two boyhood chums, first-generation sons of English and Scottish immigrants, decide that what turn-of-the-century Milwaukee really needs is a motorbike that will tackle the rutted roads of the day without shaking itself to pieces. Arthur Davidson, just 19, is a patternmaker at a local metal-fabrication shop; William Harley, 20, an apprentice draftsman at the same firm. Their quest for a suitable powerplant is aided immeasurably by a newly emigrated German coworker with knowledge (some unauthorized blueprints) of the French DeDion engine. When the boys-working late into the night in basements and borrowed shopscan’t keep their contraption running, carburetion expertise arrives in the friendly form of Norwegian-born neighbor Ole Evinrude, later of outboard-motor fame.

Harley-Davidson #001, then, a full century ago, the product of Melting Pot engineering at its finest.

In short time, Davidson’s two brothers, Walter, a skilled machinist, and William, a railroad toolroom foreman, join the fledgling outfit, giving us the “Four Founders” of familiar sepia-toned imagery. Not that the work got any easier. Recalled Walter, “It was an event when we quit work on Christmas night at 8 o’clock to attend a family reunion.”

It was William Harley, though, who can rightly be called the architect of The Motor Company. With the operation up on shaky legs, he realized further advancement would require additional engineering skills, so he enrolled in the University of Wisconsin, waiting tables at a frat house to help with tuition. Graduated in 1908, it was Harley as Chief Engineer who beefed up the original Single so it could climb hills and record perfect scores in reliability runs popular at the time. It was Harley who cast aside the breakage-prone bicycle chassis and designed a big-tube, looptype frame of high-carbon steel that gave H-Ds their hell-for-stout reputation. It was Harley who came up with the link-type front suspension, the stepstarter and the first real motorcycle clutch. And it was Harley who later oversaw R&D of the 1936 EL Knucklehead, taproot of all modern Big Twins. When he passed in 1943, dropped by a heart attack after a round of golf, William Sylvester Harley had 67 engineering patents to his name.

It would no doubt come as a shock to old Bill today, 100 years and 3.8 million machines after he and the Davidson brothers handcrafted that first onelunger, that none of the Harley bloodline is involved with the company that bears his name.

Certainly, his own sons played a big part in the company’s middle history. William J. took over as Chief Engineer upon his father’s death. A happy-looking man who favored bow ties, rode to work almost every day, summer or winter, and delighted his daughter’s schoolmates by spinning donuts with his sidecar, he penned the breakthrough K-models, meant to blunt the British bullies of the 1950s, which morphed into the Sportster line still with us today. Diabetes took the man much too early, William J. dying in 1971, aged 59, still at his post.

Younger brother John E., a Notre Dame grad, was a demon touring rider who started with the company in 1939 as a junior draftsman. When war broke out, newly enlisted Capt. Harley was put in charge of training the Army’s armored divisions at Fort Knox, further cementing ties between Harley-Davidson and the military. Discharged as a major after the war, he sat on the board of directors and was later appointed

manager of the Parts & Accessories division. He was gone by 1976, though, a cancer victim at 61.

Which brings us to John Jr., the last of the Harley clan to hold a position at the factory. Like all Harley and Davidson offspring interested in the family business, he started at the bottom, a partsshagger for “Dept. 21,” where assembly-line defects were rectified and dealer returns fixed. The year was 1975, height of the AMF quality-control bugaboos, and Dept. 21 did not lack for activity. By 1982, Harley had been promoted to the ominously titled job of Production Expeditor, but neither that nor his family name insulated him from being axed when the company, recently bought back from AMF but facing imminent bankruptcy, laid-off 1600 employees that spring.

With that flurry of pink slips, eight decades of Harley involvement in the company was unceremoniously closed out. And in the 21 years since, no one with the co-founder’s DNA has drawn a Harley-Davidson paycheck.

So, what of the last Harley? Is he bitter about being let go, fuming that none of the Harley family was in on the buyback-nor reaped big benefits in The Motor Company’s subsequent Wall Street rise?

No.. .well, at least not anymore.

“For 12 years, I didn’t even look at a motorcycle,” says Harley, now 57 and working as a mailman in a Milwaukee suburb. But a borrowed ride on an XLCR Cafe Racer-designed by another cofounder’s grandson, Willie G. Davidson-got John back on two wheels, where he’s been ever since. His current ride is a 95th Anniversary Road Glide. “A finelooking machine,” he notes.

“I can’t speak for others in the family, but for me it’s not about the money. It’s that I was not able to do what I was raised to do. I always thought I’d be part of the factory. I’m not and that’s just the way it is,” Harley says in a resigned but not angry tone.

Neither John nor sister Sarah, also an avid rider, has been asked to participate in any of the official 100th Anniversary doings, which seems like a huge PR opportunity missed, but both will attend a big Harley and Davidson family reunion, a private affair, earlier in the week.

“I’ll always respect the men, the company, the machine,” says the last Harley.