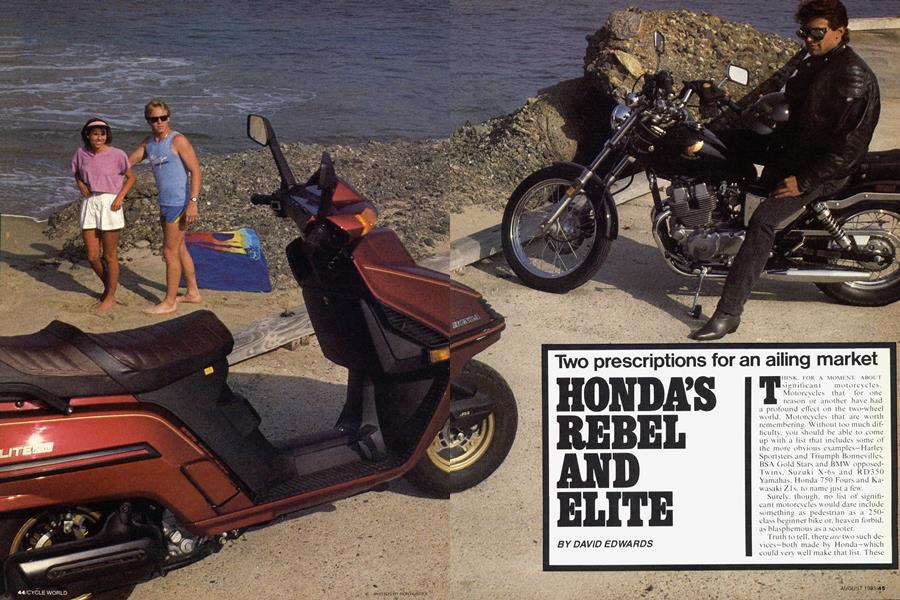

HONDA'S REBEL AND ELITE

Two prescriptions for an ailing market

DAVID EDWARDS

THINK, FOR A MOMENT, ABOUT significant motorcycles. Motorcycles that for one reason or another have had a profound effect on the two-wheel world. Motorcycles that are worth remembering. Without too much difficulty, you should be able to come up with a list that includes some of the more obvious examples—Harley Sportsters and Triumph Bonnevilles, BSA Gold Stars and BMW opposed-Twins, Suzuki X-6s and RD350 Yamahas, Honda 750 Fours and Kawasaki Z1s, to name just a few.

Surely, though, no list of significant motorcycles would dare include something as pedestrian as a 250class beginner bike or. heaven forbid, as blasphemous as a scooter.

Truth to tell, there are two such devices—both made by Honda—which could very well make that list. These two unlikely contenders are the Rebel, a 234cc, entry-level bike with extremely, er, “American” styling, and the Elite 250. the freeway-legal flagship of Honda’s seven-bike scooter lineup.

And why, you may well ask, are these two vehicles poised on the very edge of significance? Well, it has nothing to do with speed or technological breakthroughs or something as poetic as the sound of a rumpetyrump exhaust note. No, these two motorcycles may become ultra-important because if Honda’s product planners are right, the Rebel and the Elite will succeed in an area where even the most super of superbikes and the most macho of cruisers have failed: bringing new riders into the motorcycle market.

Talk to many people in the motorcycle industry about its current state of affairs, and one word keeps popping up with distressing regularity: stagnant. Over the past few years, sales of street-legal motorcycles in the U.S. have dipped considerably, and they seem to be leveling off at a point far below the peak volumes reached in the late Seventies. Of the current market, Honda commands approximately a 55-percent share, Yamaha's is close to 20, Suzuki owns about 12 percent and Kawasaki 8. Although those percentages move around a few points each model year, the proportions remain fairly constant; and, more important, so does the total number of units sold.

In other words, there just aren’t enough new riders being attracted to motorcycling. This so disturbed the powers-that-be at Honda that they commissioned some university-level research into the problem; as a result, out of the corporate think-tank rolled the Rebel and the Elite.

It’s not hard to see where the Rebel's designers got their inspiration. Because to be blunt about it, the Rebel is a %-scale Harley-Davidson. Even the most staunch defenders of Honda’s custom-bike styling—the ones who insist that Honda cruisers have the American look and are not meant to be Harley clones—don’t put up much of a fight where this model is concerned. With its peanut fuel tank, bobbed and chrome-railed rear fender, moved-up shocks, two-piece seat and plated mini-headlight, the Rebel is too blatant for that.

Nevertheless, the styling works, and the Rebel pulls off the mini-Harley act as cleanly as if it actually had been styled by Willie G. himself. In fact, Harley-Davidson doesn't feel at all threatened by the Rebel. Instead, H-D's top brass believes that this little Honda will teach new buyers to appreciate Milwaukee-styled motorcycles so that when they’re ready for a “real” bike, they’ll be more inclined to move up to the real thing—a Harley, of course.

Indeed, unlike the tarted-up, cruiser-style beginner bikes of recent years, the Rebel isn't a joke; its proportions are correct, its lines pleasing. It looks like a motorcycle. And for that, Honda should get some kind of most-improved award. Because the bike upon which the Rebel is mechanically based is the CM 185 TwinStar. a bottom-feeder of a motorcycle that the Cycle World staff in 1 977 summed up nicely: “It is simply not a proper motorcycle ... a toy not to be taken seriously.”

To make the transformation, the TwinStar's wheelbase was stretched seven inches, giving the prerequisite long-low-and-lean look. A longer, stouter front fork, complete with disc brake, was grafted on up front. The electric-start, single-overhead-cam, two-valve engine, with design roots dating clear back to the CB175 Twins of the late Sixties and early Seventies, was stroked to 234cc and treated to more-substantial cylinder finning. The engine also got a 28mm Keihin CV carburetor, up from the 185’s 22mm instrument. A 15-inch rear tire and an 18-incher up front gave the proper fat-to-skinny rubber ratio. Then the aforementioned styling treatment was laid on, and—voila— lackluster TwinStar was recast into blockbuster Rebel.

Honda is counting on the Rebel’s looks to lure new shoppers into the showroom. And once those prospective buyers are inside, Honda figures, the low purchase price of $1299 should be enough to persuade a lot of aspiring motorcyclists to sign on the dotted line.

Certainly a test ride would do nothing to dispel a potential customer’s rapture. With a low, 26-inch seat height, a reach-out-and-shake handlebar position and a topped-up weight of just 333 pounds, the Rebel is easy to push around the parking lot and unintimidating during wobbly, feet-down, first-gear maneuvering.

Once underway and shifted through its slightly notchy, fivespeed transmission, the Rebel refuses to display any of the twitchy, indecisive behavior that is characteristic of so many little bikes. The ride is decent, for the suspension does a credible job of insulating the rider from bumps. The Rebel even is game for some short-range touring, so long as you don't mind footpeg, handlebar and seat vibration that can be annoying at freeway speeds, and a seat that, while comfortable in-town, becomes tiring after an hour or so. And the passenger's seat —a fender pad. really— is much too sparse for extended trips.

In town, the pumped-up engine has enough steam to pull away from all but the most determined fourwheelers. and delivers 65 miles to the gallon in the process. And even if the Rebel’s acceleration is fairly unimpressive by motorcycle standards, its stopping distance from 60 mph is simply astounding. At 112 feet, which is a full 20 feet shorter than some of the new-generation sportbikes have been able to manage, the Rebel’s stopping distance is the best in recent Cycle World history.

If the Rebel is as American as baseball. apple pie, hot dogs and HarleyDavidsons, then the Elite 250 scooter is as American as a Mary Lou Retton floor-exercise routine: all bubbly, vibrant and cute.

But don’t make the mistake of dismissing this particular scooter as some 1 6-year-old’s after-school plaything: It is a serious transportation device. And take our word for it, there is nothing short of a runaway Sherman tank that will slice through a knot of snarled cars quicker and with more ease than an Elite 250. In the hands of a resourceful rider, the Elite—which looks as if it might have escaped from a 1960s Ann-Margretromps-th rough-Eu rope movie—becomes the ultimate point-and-squirt urban assault vehicle capable of leaving any other two-wheeler in the wake of its socially acceptable exhaust note.

The reason the Elite excels in this kind of block-to-block warfare is fairly straight-forward: It is the VMax of the scooter set. Powered by a liquid-cooled, 244cc, single-cylinder four-stroke, the Elite is the largestdisplacement scooter currently sold in the U.S. Even with its 1.94-gallon, under-seat fuel tank brimming, the 30 1 -pound Elite is capable of performance not far below that of the Rebel, which makes it more than a match for the normal flow of traffic. And while it is a speed demon compared to its less-muscled stablemates, the 250 keeps the genre’s reputation for miserly fuel consumption alive with readings in the 75-mpg range.

And, of course, there are other features that make the Elite stand out. First on the list is the V-matic automatic transmission, Honda’s beltdriven system of two variable-diameter pulleys that smoothly transmits the engine's power to the rear wheel. Getting the Elite underway is as easy as twisting the throttle grip, placing your feet on the floorboards and steering the thing between the yellow lines. It's simpler than a bicycle.

From a motorcyclist's viewpoint, about the only disturbing aspects of the Elite's performance are its lessthan-stellar front brake and its slight twitchiness when ridden at or near top speed on the freeway.

Still, those minor complaints will be overlooked by the average scooter buyer. Add electric starting to the basic package, along with a complete array of LCD digital instruments, a glove compartment, a luggage rack and a seat more comfortable than those on most motorcycles, and it's easy to see why scooters in general are selling so well.

Actually, “selling w'ell" is an understatement. Honda officials expect scooter sales to outdistance both motorcycle and all-terrain-vehicle sales within five years. “We're going after fantastic numbers," they say. “Scooters are going to be a very, very valuable market for Honda.”

Whether or not those “fantastic numbers" of scooters w ill eventually translate into increased motorcycle sales remains to be seen. Although scooter advertising so far has been targeted at non-motorcycle enthusiasts, Honda's researchers have detected some crossover sales, albeit they're quite small at this point. But the Elite is one scooter that’s just so plain likable that it makes Honda’s ambitious predictions for that market

easy to believe. And as far as the Rebel's ability to lure new' people into the sport is concerned, the bike is slick enough and priced low enough that it seems sure to succeed.

So one way or another, it is likely that both of these machines will be responsible for putting a lot more people on two wheels. It’s also likely

that many hard-core motorcyclists who traditionally despise scooters and small motorcycles will take one look at these two and dismiss them as “dumb.” But these days, anything that can administer a little muchneeded first aid to an ailing motorcycle business would be more appropriately called a “blessing." E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

August 1985 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

August 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1985 -

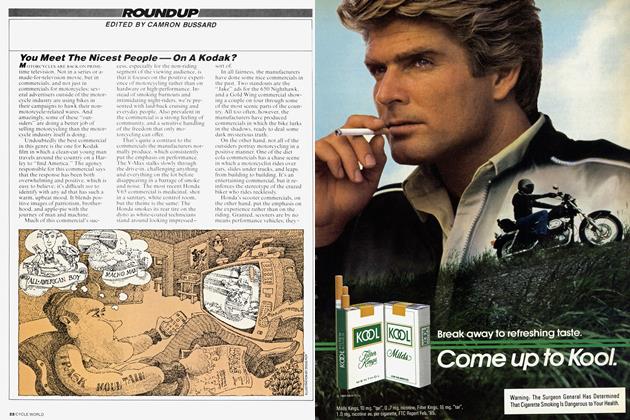

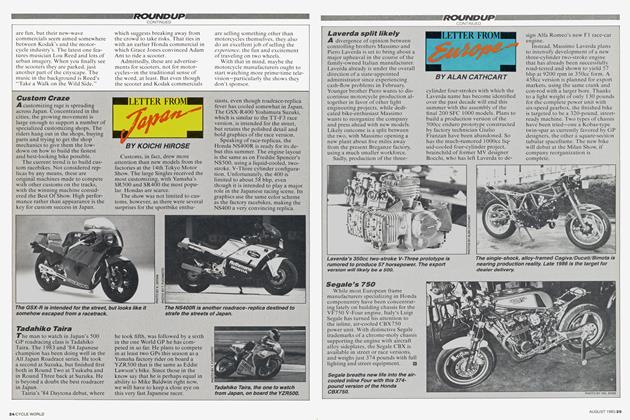

Roundup

RoundupYou Meet the Nicest People—On A Kodak?

August 1985 By Camron Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

August 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

August 1985 By Alan Cathcart