UP FRONT

Charge of the Light Brigade

David Edwards

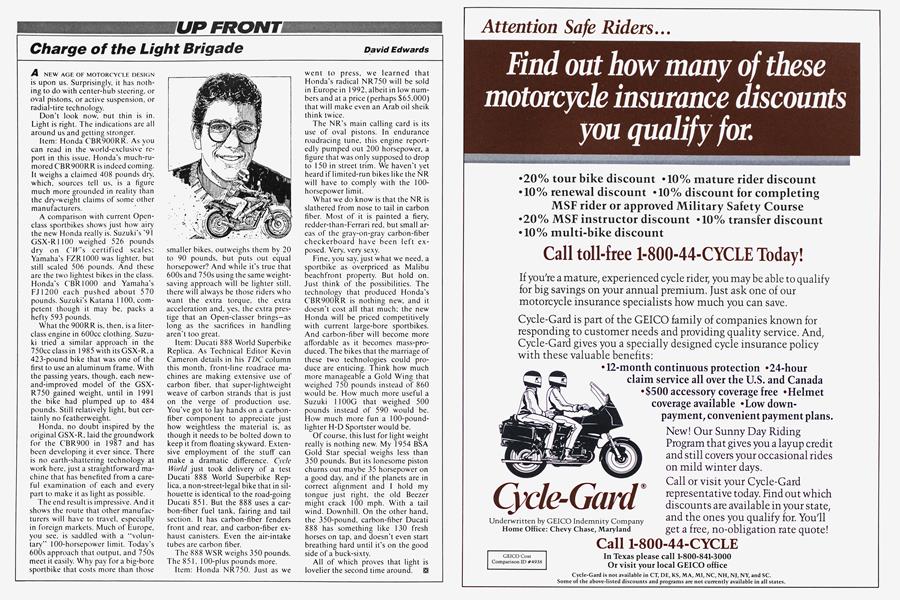

A NEW AGE OF MOTORCYCLE DESIGN is upon us. Surprisingly, it has nothing to do with center-hub steering, or oval pistons, or active suspension, or radial-tire technology.

Don’t look now, nut thin is in. Light is right. The indications are all around us and getting stronger.

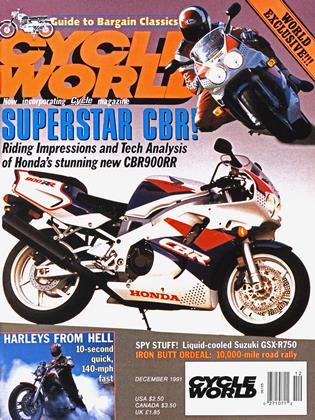

Item: Honda CBR900RR. As you can read in the world-exclusive report in this issue. Honda’s much-rumored CBR900RR is indeed coming. It weighs a claimed 408 pounds dry, which, sources tell us, is a figure much more grounded in reality than the dry-weight claims of some other manufacturers.

A comparison with current Openclass sportbikes shows just how airy the new Honda really is. Suzuki’s '91 GSX-R 1100 weighed 526 pounds dry on CW's certified scales: Yamaha’s FZR1000 was lighter, but still scaled 506 pounds. And these are the two lightest bikes in the class. Honda's CBR 1000 and Yamaha's FJ1200 each pushed about 570 pounds. Suzuki's Katana 1 100, competent though it may be, packs a hefty 593 pounds.

What the 900RR is, then, is a literclass engine in 600cc clothing. Suzuki tried a similar approach in the 750cc class in 1985 with its GSX-R, a 423-pound bike that was one of the first to use an aluminum frame. With the passing years, though, each newand-improved model of the GSXR750 gained weight, until in 1991 the bike had plumped up to 484 pounds. Still relatively light, but certainly no featherweight.

Honda, no doubt inspired by the original GSX-R, laid the groundwork for the CBR900 in 1987 and has been developing it ever since. There is no earth-shattering technology at work here, just a straightforward machine that has benefited from a careful examination of each and every part to make it as light as possible.

The end result is impressive. And it shows the route that other manufacturers will have to travel, especially in foreign markets. Much of Europe, you see, is saddled with a “voluntary” 100-horsepower limit. Today’s 60()s approach that output, and 750s meet it easily. Why pay fora big-bore sportbike that costs more than those smaller bikes, outweighs them by 20 to 90 pounds, but puts out equal horsepower? And while it's true that 600s and 750s using the same weightsaving approach will be lighter still, there will always be those riders who want the extra torque, the extra acceleration and, yes. the extra prestige that an Open-classer brings—as long as the sacrifices in handling aren't too great.

Item: Ducati 888 World Superbike Replica. As Technical Editor Kevin Cameron details in his TDC column this month, front-line roadrace machines are making extensive use of carbon fiber, that super-lightweight weave of carbon strands that is just on the verge of production use. You've got to lay hands on a carbonfiber component to appreciate just how weightless the material is, as though it needs to be bolted down to keep it from floating skyward. Extensive employment of the stuff can make a dramatic difference. Cycle World just took delivery of a test Ducati 888 World Superbike Replica, a non-street-legal bike that in silhouette is identical to the road-going Ducati 851. But the 888 uses a carbon-fiber fuel tank, fairing and tail section. It has carbon-fiber fenders front and rear, and carbon-fiber exhaust canisters. Even the air-intake tubes are carbon fiber.

The 888 WSR weighs 350 pounds. The 851.100-plus pounds more.

Item: Honda NR750. Just as we went to press, we learned that Honda’s radical NR750 will be sold in Europe in 1992, albeit in low numbers and at a price (perhaps $65,000) that will make even an Arab oil sheik think twice.

The NR’s main calling card is its use of oval pistons. In endurance roadracing tune, this engine reportedly pumped out 200 horsepower, a figure that was only supposed to drop to 150 in street trim. We haven't yet heard if limited-run bikes like the NR will have to comply with the 100horsepower limit.

What we do know is that the NR is slathered from nose to tail in carbon fiber. Most of it is painted a fiery, redder-than-Ferrari red, but small areas of the gray-on-gray carbon-fiber checkerboard have been left exposed. Very, very sexy.

Fine, you say, just what we need, a sportbike as overpriced as Malibu beachfront property. But hold on. Just think of the possibilities. The technology that produced Honda’s CBR900RR is nothing new, and it doesn't cost all that much; the new Honda will be priced competitively with current large-bore sportbikes. And carbon-fiber will become more affordable as it becomes mass-produced. The bikes that the marriage of these two technologies could produce are enticing. Think how much more manageable a Gold Wing that weighed 750 pounds instead of 860 would be. How much more useful a Suzuki 1100G that weighed 500 pounds instead of 590 would be. How much more fun a 100-poundlighter H-D Sportster would be.

Of course, this lust for light weight really is nothing new. My 1954 BSA Gold Star special weighs less than 350 pounds. But its lonesome piston churns out maybe 35 horsepower on a good day, and if the planets are in correct alignment and 1 hold my tongue just right, the old Beezer might crack 100 mph. With a tail wind. Downhill. On the other hand, the 350-pound, carbon-fiber Ducati 888 has something like 130 fresh horses on tap, and doesn’t even start breathing hard until it’s on the good side of a buck-sixty.

All of which proves that light is lovelier the second time around.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

December 1991 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

December 1991 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1991 -

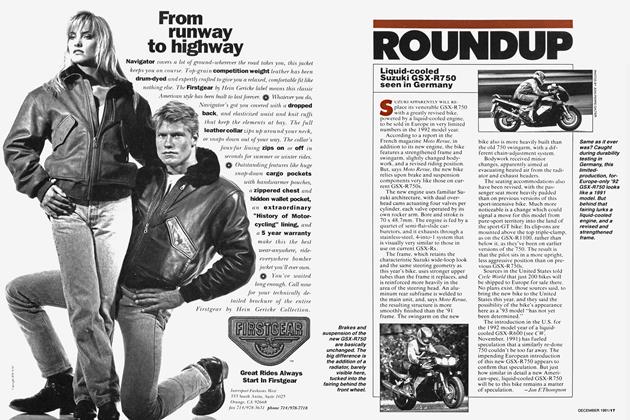

Roundup

RoundupLiquid-Cooled Suzuki Gsx-R750 Seen In Germany

December 1991 By Jon F.Thompson -

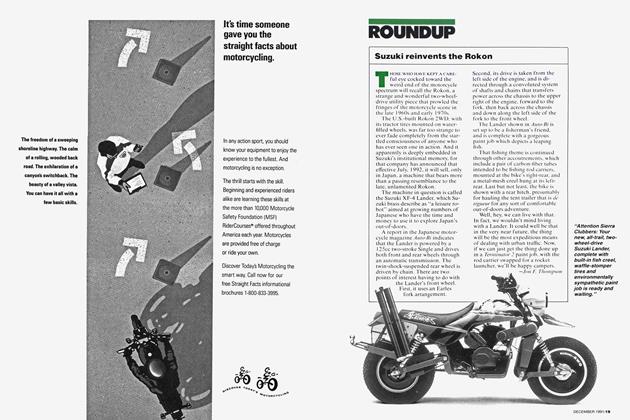

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Reinvents the Rokon

December 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

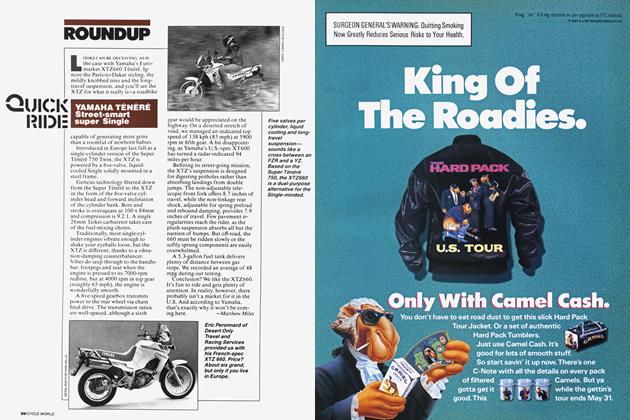

RoundupQuick Ride

December 1991 By Matthew Miles