LEANINGS

Goodbye, Mr. Honda

Peter Egan

MR. SOICHIRO HONDA IS NO LONGER with us. I read in the papers he died on August 5th, in Tokyo.

The story said he was born in 1906, that he was 84 years old. That’s eight years older than my father. Is this possible?

The overlap of generations—and the effect of one generation on an-other—is a strange thing. Those of us who think of ourselves as America’s post-war baby boomers are, on the average, a good 40 years younger than Soichiro Honda was, and yet somehow I can’t help believing he really belongs to our generation. Before anyone else does, I think we should claim him for our own.

The simple fact is, his genius and his years of accumulated knowhow really came into full bloom just about the time many of us became speed-crazed teenagers. (Or. in the case of the Honda 50. merely motion-crazed teenagers.) The invasion of Honda’s small, well-engineered and inexpensive motorcycles dovetailed perfectly with our coming of age and filled a great vacuum that no one else seemed to have noticed.

Many of us. now approaching our mid-40s, were already hanging around motorcycle shops and lusting after Harleys and Triumphs before we ever heard the name Honda. We wanted bikes badly, but our options were limited. Big bikes were out of the question, financially and parentally speaking (and boy, did they speak), but the traditional motorcycle companies just didn't offer much in the way of cheap, small-bore equipment.

So we high school kids were largely stuck with such choices as ( I ) Whizzer conversion kits for old Schwinns; (2) mini-bike kits with go-kart wheels and lawn-mower engines; (3) used Harley Hummers with piston rattle; or (4) Cushman scooters with variable belt drive and styling borrowed from an ice-cream delivery truck.

Contraptions, in other words. Mostly cantankerous little devices that hugged the shoulder of the road while smoking heavily, balking at hills and burning out their tiny centrifugal clutches, if they were lucky enough to have them.

Then, suddenly, there were Hondas. Word spread like wildfire, and so did the bikes, all through the early Sixties.

The price range was $245 to $700 new, depending on the model. Most models (other than the 50cc stepthrough) had slick, four-speed tranmissions hidden inside engine cases, where they couldn’t even snag your pants cuff and leave grease marks. Electricity actually reached the headlight, which in turn lit the road. Performance, percc, was amazing. A Honda Super 90 would go about 60 on the highway while getting around 100 mpg. The CB160 was quicker than most of the old 250 British Singles and cost less. The 305 Super Hawk was a giant killer. What's more, these bikes looked good. Someone in Japan understood. Goodbye, Cushman.

Until Hondas arrived, motorcycle technology seemed to have lagged well behind modern standards for cars and aircraft. It was assumed, for reasons I will never understand, that motorcycles had to be wrenched upon constantly, that they were destined to leak oil and vibrate excessively. scattering parts and vaporizing light filaments.

Perhaps I'm painting too bleak a picture of the pre-Honda era, as there were many fine and relatively refined bikes made earlier, but the majority of Fifties motorcycles had what seemed to me a World War I aircraft flavor to their mechanical innards— and ou tards. (“Advance the spark. Biggies! We've a Hun on our tail.”)

My own first bike was not a Honda. After a brief fling with a semifunctional James/Villiers 150, I bought a Bridgestone Sport 50, mainly because we had a local dealer. A good little bike, but it was a twostroke and had the usual oil-mix/ plug-range hassles.

Shortly thereafter, I got a Honda Super 90 and decided I was a fourstroke kind of a guy. After that, I owned 10 more Hondas of progressively larger displacement, sampling other brands of Japanese bikes only when they, too, converted to fourstroke engines. (My old Yamaha RD350 being the only stray.)

Through all those years of Honda ownership, the company—or maybe the old man himself—always seemed to know exactly what I wanted next, before the thought was fully formed in my head. Or, more likely, Mr. Honda simply built what he knew was right, and his ideas made sense when I saw them. In any case, I always felt as if I had a friend in Japan, a kindred spirit who could interpret mechanically what I could not express.

I never met Soichiro Honda. I know him only from his upbeat, candid autobiography, his life’s work and from his portrait, which has hung on the wall above my desk for years, right next to that of Ducati’s Dr. Taglioni. Like Taglioni, Honda belongs to that small pantheon of engineers who managed to bring both irrepressible character and expertise with them to the drafting table.

You have to have owned a motorcycle designed by an individual (or worse, a committee) where one of those two traits is missing to appreciate what we’ve lost.

What else can I say? Mr. Honda’s bikes took me across Canada, through college, off to visit my girlfriend on a summer of weekends, around the track on my first season of roadracing, down Highway 61 to New Orleans, across the Mojave Desert, up Pike's Peak, touring with my new bride and on a mad autumn dash to the USGP at Watkins Glen. And back. Always back.

Eleven bikes, and none of them ever let me down. Not once.

Thank you. Mr. Honda. They were good times, all.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

December 1991 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

December 1991 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1991 -

Roundup

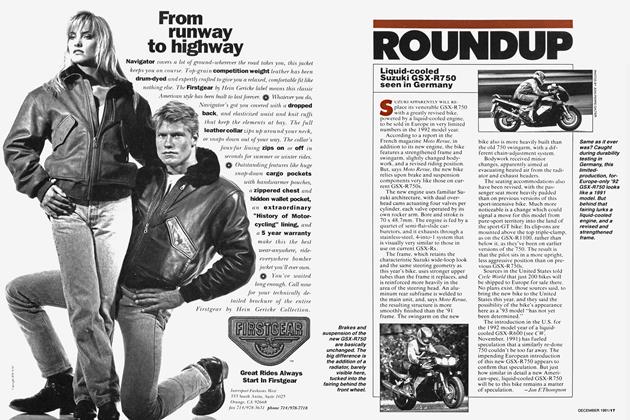

RoundupLiquid-Cooled Suzuki Gsx-R750 Seen In Germany

December 1991 By Jon F.Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Reinvents the Rokon

December 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

December 1991 By Matthew Miles