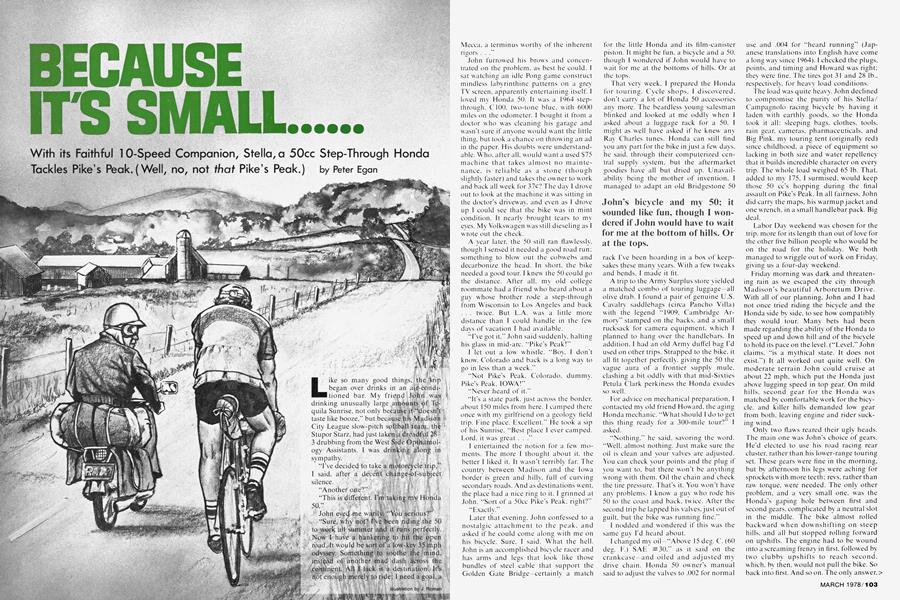

BECAUSE IT'S SMALL......

With its Faithful 10-Speed Companion, Stella, a 50cc Step-Through Honda Tackles Pike’s Peak.(Well, no, not that Pike’s Peak.)

Peter Egan

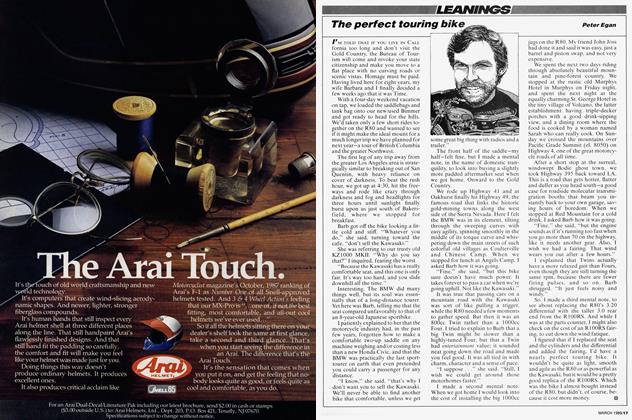

Like so many good things, the trip began over drinks in an aif-condi-

tioned bar. My friend John was drinking unusually large amounts of Tequila Sunrise, not only because it “doesn’t taste like booze,” but because his Madison City League slow-pitch softball team, the Stupor Starz, had just taken a dreadful 28— 3 drubbing from the West Side Opthamology Assistants. I was drinking along in sympathy.

“I’ve decided to take a motorcycle trip.”

I said, after a decent change-of-subjeet silence.

“Another one?”

“This is different. Ip taking my Honda 50.”

John eyed me warily. “You serious?” “Sure, why not? I've been riding the 50 to work all summer and it runs perfectly.

Now I have a hankering to hit the open road. It would be sort of a low-key 35 mph odyssey. Something to soothe the mind.

instead of another mad dash across the Incontinent. Alt I lack is a destination. It’s not enough merely to ride; 1 need a goal, a Mecca, a terminus worthy of the inherent rigors . .

John furrowed his brows and concentrated on the problem, as best he could. I sat watching an idle Pong game construct mindless labyrinthine patterns on a grey TV screen, apparently entertaining itself. I loved my Honda 50. It was a 1964 stepthrough. C100, two-tone blue, with 6000 miles on the odometer. 1 bought it from a doctor who was cleaning his garage and wasn't sure if anyone would want the little thing, but took a chance on throwing an ad in the paper. His doubts were understandable. Who, after all. would want a used $75 machine that takes almost no maintenance, is reliable as a stone (though slightly faster) and takes the owner to work and back all week for 37c? The day I drove out to look at the machine it was sitting in the doctor’s driveway, and even as 1 drove up I could see that the bike was in mint condition. It nearly brought tears to my eyes. My Volkswagen was still dieseling as I wrote out the check.

A year later, the 50 still ran flawlessly, though I sensed it needed a good road run; something to blow out the cobwebs and decarbonize the head. In short, the bike needed a good tour. I knew the 50 could go the distance. After all, my old college roommate had a friend who heard about a guy whose brother rode a step-through from Wisconsin to Los Angeles and back . . . twice. But L.A. was a little more distance than I could handle in the few days of vacation I had available.

“I’ve got it.” John said suddenly, halting his glass in mid-arc. “Pike’s Peak!”

I let out a low whistle. “Boy, I don’t know. Colorado and back is a long way to go in less than a week.”

“Not Pike's Peak. Colorado, dummy. Pike’s Peak, IOWA!”

“Never heard of it."

“It's a state park, just across the border, about 150 miles from here. I camped there once with my girlfriend on a geology field trip. Fine place. Excellent.” He took a sip of his Sunrise. “Best place I ever camped. Lord, it was great ...”

I entertained the notion for a few moments. The more I thought about it. the better I liked it. It wasn't terribly far. The country between Madison and the Iowa border is green and hilly, full of curving secondary roads. And as destinations went, the place had a nice ring to it. I grinned at John. “Sort of a 50cc Pike's Peak, right?” “Exactly.”

Later that evening. John confessed to a nostalgic attachment to the peak, and asked if he could come along with me on his bicycle. Sure. I said. What the hell. John is an accomplished bicycle racer and has arms and legs that look like those bundles of steel cable that support the Golden Gate Bridge—certainly a match for the little Honda and its film-canister piston. It might be fun, a bicycle and a 50, though I wondered if John would have to wait for me at the bottoms of hills. Or at the tops.

That very week, I prepared the Honda for touring. Cycle shops, I discovered, don't carry a lot of Honda 50 accessories any more. The beardless young salesman blinked and looked at me oddly when I asked about a luggage rack for a 50. I might as well have asked if he knew any Ray Charles tunes. Honda can still find you any part for the bike in just a few days, he said, through their computerized central supply system, but the aftermarket goodies have all but dried up. Unavailability being the mother of invention, I managed to adapt an old Bridgestone 50

John’s bicycle and my 50; it sounded like fun, though I wondered if John would have to wait for me at the bottom of hills. Or at the tops.

rack I’ve been hoarding in a box of keepsakes these many years. With a few tweaks and bends, I made it fit.

A trip to the Army Surplus store y ielded a matched combo of touring luggage—all olive drab. I found a pair of genuine U.S. Cavalry saddlebags (circa Pancho Villa) with the legend “1909. Cambridge Armory” stamped on the backs, and a small rucksack for camera equipment, which I planned to hang over the handlebars. In addition. I had an old Army duffel bag I'd used on other trips. Strapped to the bike, it all fit together perfectly, giving the 50 the vague aura of a frontier supply mule, clashing a bit oddly w ith that mid-Sixties Petula Clark perkiness the Honda exudes so well.

For advice on mechanical preparation, I contacted my old friend Howard, the aging Honda mechanic. “What should I do to get this thing ready for a 300-mile tour?" I asked.

“Nothing,” he said, savoring the word. “Well, almost nothing. Just make sure the oil is clean and your valves are adjusted. You can check your points and the plug if you want to. but there won't be anything wrong w ith them. Oil the chain and check the tire pressure. That's it. You won't have any problems. I know a guy who rode his 50 to the coast and back, twice. After the second trip he lapped his valves, just out of guilt, but the bike was running fine.”

I nodded and wondered if this was the same guv I'd heard about.

I changed my oil—“Above 15 deg. C. (60 deg. F.) SAE =30.” as it said on the crankcase—and oiled and adjusted my drive chain. Honda 50 owner’s manual said to adjust the valves to .002 for normal use and .004 for “heard running” (Japanese translations into English have eome a long way since 1964). I checked the plugs, points, and timing and Howard was right; they were fine. The tires got 31 and 28 lb., respectively, for heavy load conditions.

The load was quite heavy. John declined to compromise the purity of his Stella/ Campagnolo raeing bicycle by having it laden with earthly goods, so the Honda took it all: sleeping bags, clothes, tools, rain gear, cameras, pharmaceuticals, and Big Pink, my touring tent (originally red) since childhood, a piece of equipment so lacking in both size and water repellency that it builds incredible character on every trip. The whole load weighed 65 lb. That, added to my 175, I surmised, w'ould keep those 50 cc's hopping during the final assault on Pike's Peak. In all fairness. John did carry the maps, his warmup jacket and one wrench, in a small handlebar pack. Big deal.

Labor Day weekend was chosen for the trip, more for its length than out of love for the other five billion people w'ho would be on the road for the holiday. We both managed to w riggle out of work on Friday, giving us a four-day weekend.

Friday morning was dark and threatening rain as we escaped the city through Madison’s beautiful Arboretum Drive. With all of our planning. John and I had not once tried riding the bicycle and the Honda side by side, to see how compatibly they would tour. Many bets had been made regarding the ability of the Honda to speed up and down hill and of the bicycle to hold its pace on the level. (“Level.” John claims, “is a mythical state. It does not exist.”) It all worked out quite well. On moderate terrain John could cruise at about 22 mph, which put the Honda just above lugging speed in top gear. On mild hills, second gear for the Honda w?as matched by comfortable work for the bicycle. and killer hills demanded low' gear from both, leaving engine and rider sucking wind.

Only two flaws reared their ugly heads. The main one was John’s choice of gears. He'd elected to use his road racing rear cluster, rather than his lower-range touring set. These gears were fine in the morning, but by afternoon his legs were aching for sprockets w ith more teeth; revs, rather than raw torque, were needed. The only other problem, and a very small one, was the Honda’s gaping hole between first and second gears, complicated by a neutral slot in the middle. The bike almost rolled backward when downshifting on steep hills, and all but stopped rolling forward on upshifts. The engine had to be wound into a screaming frenzy in first, followed by two clubby upshifts to reach second, which, by then, would not pull the bike. So back into first. And so on. The only answer.>

1 discovered, was to be At One w ith very, very, slowr speeds; to enjoy the birds and the trees and the sky as the Honda churned along in first gear, a tiny mechanical Juggernaut devouring hills as inexorably and relentlessly as a glacier.

Our route was lifted straight off the dotted red lines of a bicycle touring map of southwestern Wisconsin, and the roads were well chosen. Even on Labor Day, traffic was virtually non-existent except when we chanced into larger towns or when one of our country roads crossed a major highway. At the main artery crossroads, we were treated to a vision of vacationing Americans acting out some sort of lemming nightmare, crawling along bumper-to-bumper with their boats and motorhomes and trailers. And yes, there were even some motorcycles in there, poor devils, all going . . . somewhere. But minutes later we would be back on the country roads with curves and fields, farms and old stone houses. No cars.

A few' hours into the trip we rolled into a small glen that sheltered a cluster of buildings called Postville; a general store with gas pumps, a real blacksmith shop across the street, five houses and a mobile home.

On the corner, right in front of the blacksmith shop, stood an old Triumph Bonneville. The bike was that rarest of aged Bonnies, the complete, original, unchopped. and fairly clean variety (these defenseless motorcycles seem to attract more than their share of vandal-owners). It w as parked at the corner of the lot in such a way as to suggest it might be for sale. I looked for a fallen sign, but found none. The blacksmith shop was closed. The general store was closed. The gas pumps were locked. Not one thing moved in the village. I knocked at all five houses and the mobile home to ask about the bike, but no one answered. Wind chimes on someone’s porch made brittle, random music in the light breeze. It was all quite eerie, and I found myself humming the theme from “On the Beach” and scanning the village for Rod Serling. I took a last, longing look at the beautiful, restorable old Bonneville. Restoring vehicles is a disease with me, and this one cried to be taken home and made to run again (the plug wires were missing). Then we got on our bikes and left.

Bv evening we were in Mineral Point, an old Cornish lead-mining town with many of its old stone miners’ cottages restored to landmark condition. John and 1 dined at the Red Rooster Cafe on Cornish Pastys (sic), a delicious sort of meat and vegetable pie. After dinner, we decided to get our nightmares over early and see “Exorcist II” at the local theater. I can’t resist movies in small-town theaters when I’m touring, and I’ll go to see anything the industry can throw at me as John discovered to his dismay. We came out onto a late-night square full of prowling muscle cars and chubby girls who shouted things at them from the street corners. We rode just out of town to our campground-by-the-highway, w here we were lulled to sleep by the music of many semis upshifting their way past our tent and off into the night.

I awoke before John in the morning and craw led out of the tent to find that the last two feet of his sleeping bag were sticking out of Big Pink like a blue tongue (John is 6'4" and the tent is 4'x4'), and that a brief night shower had soaked the end of his bag. Not only that, a huge orange cat had nested in a pocket of sodden goose down between his feet. Nothing disturbs the sleep of the touring bicyclist. On our trip John slept so hard that he actually frowned from the effort.

My first gas stop, on the second morning. revealed that the Honda had guzzled no less than half a gallon during the 80 miles we'd covered the previous day. at a cost of 32C. That was 160 mpg. John was numb. “Thirty-two cents? That’s crazy! Hell. I spent over a dollar on granola bars yesterday, just so I'd have enough energy to pedal this bike.” He stared at the Honda with a troubled frown, as if trying to grasp some searing new truth. “That’s plain madness. You can’t make a gas tank leak that slowly, much less run a vehicle . . .”

That same day. we hit our highest mutual speed of the trip while racing down a long hill (one of those inclines so evil that a sign at the top says HILL, and shows a truck perched on a steep triangle). We reached 46 mph. wheel to w heel, just as the road bottomed onto a one-lane bridge w hose ramp-like apron nearly tossed us off' our bikes. We got into the low 40s a few times after that, but never again broke the magic 46. Uphills were less speedy that day. when a strong wind shifted into our faces. The Honda was unbothered by the wind at low speeds but the bicycle’s progress took a quantum leap downward and John appeared to be pedaling in a slowmotion bionic frenzy.

We had a late lunch at a small cafe in Lancaster, a small city whose skyline is dominated by two landmarks; an intricate green glass dome on the Grant County Courthouse, and one of those space-age water towers that look like giant turquoise golf balls. “Some day,” I told John as we rode into town, “God, with his enraged sense of aesthetics, will descend from heaven with a giant fiery Gary Playerautographed driver and tee off on all those water towers and then we won’t have to see them any more.” John nodded grimly, sweat running off his nose. He loved to joke while pedaling into the wind.

continued on page 108

continued from page 104

We ate at Bud’s, where the waitress, seeing our bikes outside, asked if we were in some kind of contest. John looked up suddenly and in a hoarse, distracted voice said, “Huh?” Proof that fatigue was setting in. Normally, he would have said something like, “Yeah, we’re trying to see who can leave the smallest tip at restaurants,” card that he is.

Toward evening we were blessed by the long descent into the Mississippi River Valley at Prairie du Chien. The town was crawling with Labor Day tourists and our hopes of finding a motel (and a shower for John, who was beginning to smell like the Chicago Bears), were soon dashed. We ended up at a commercial campground right next to the river. As we were about to register, the manager asked if we had a pup tent. We nodded. He closed the registration book and pointed to a sign that said “No Pup Tents.”

“Can’t allow them any more,” he said sadly. “Last year a motorhome backed over a pup tent with two campers in it, and now the insurance company won’t allow any tent that isn’t tall enough to be seen in truck mirrors.” John and I turned to each other, incredulous. A campground that doesn’t allow pup tents? Crazy. I looked around at the gleaming row of campers, trailers and motorhomes. I suddenly felt like I’d drifted into camp from another era, some kind of Dust Bowl Okie, with my miserable little canvas tent and only a sleeping bag to put in it. John looked so forlorn at the prospect of more pedaling and searching that the camp manager was moved. “I’ll tell you what. I’ve got a Jeep camper by the house. You can sleep in that.” We gladly accepted. He apologized for the rules several times. He didn’t like it any more than we did, but it was the insurance.

Living well being the best revenge, we got even for our lack of motel that night by eating steak and lobster at the Blue Heaven Supper Club, a place with tiny blinking lights embedded in the blue ceiling, and cherubs on the walls. Later, we saw “Joyride” at the theater on Main Street. John’s resistance to the nightly movie was building, I sensed. When we came out the street was almost violently alive with drunks, more muscle cars, big motorcycles, shouting youth, cruising squad cars and roving bands of cowboys in town for a rodeo. Sundown on Labor Day. By the time we returned to the campground, it seemed like a very good place. It was soothingly peaceful; dotted with campfires, Japanese lanterns and murmuring circles of friends. John went right to sleep in the truck and I walked down to the willows at the edge of the river and sat on the shore, enjoying the quiet and smoking a corncob pipe I’d bought off a cardboard display at a cafe—something I’d wanted to do ever since I read Tom Sawyer at the age of 10. The Mississippi, when you sit next to it at night, is a dark and powerful thing.

Prairie du Chien was our final camp in the assault on Pike’s Peak. On a bright Sunday morning we rolled across the Mississippi bridge into Iowa and began the climb out of the town of McGregor. It was

The ride was 303 miles long and the Honda used 1,8 gallons of fuel at a cost of $1.13. John ate about $4 worth of granola bars while riding the bicycle.

strictly low gear for Honda and Stella but after a 15-minute ascent, we wheezed into Pike’s Peak State Park. We had a man take our picture at the gate, then went directly to the highest spot on the Peak (which is really a bluff overlooking the Mississippi) and planted a tiny Wisconsin State Flag to commemorate our conquest. We savored the magnificent view of the junction of the Wisconsin and Mississippi Rivers in the valley far below, and read a tourist leaflet explaining that Zebulon Pike had picked this spot for a U.S. fort during an exploration trip in 1805, but that the government, always seeking the lower ground, had eventually built the fort next to the river, in Prairie du Chien.

At the park concession stand, we bought postcards, T-shirts, ice cream, and a corncob pipe with “Pike’s Peak” burned into the stem. Mailing all those cards telling people we’d made it was a glorious moment.

We coasted back across the river into Wisconsin, and turned up the Wisconsin River valley to head for home. That night we finally found indoor lodging. An ancient hotel in Muscoda (pronounced Muskah-day) took us in for $11. The place had beautiful old woodwork, a lobby with a potted fern, spotlessly clean rooms that looked like something from “Gunsmoke,” and, best of all, a bathroom with a shower at the end of the hall. John returned from the shower reborn. We dined on catfish at the Blackhawk Supper Club to celebrate his cleanliness. After dinner, John refused to take in “Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger” at the local Bijou, so we went to the hotel bar and I called my wife, who was much relieved to hear that we still existed. That night, John and I discovered that Muscoda has the world’s highest per capita population of Harley-Davidsons with straight pipes. All of them patronize the bar across the street from our hotel window, taking turns doing demonstration burn-outs on Main Street for a throng of cheering drag fans.

In the morning we had breakfast at the Chieftain’s Teepee, feeling a little out of place as the only customers not wearing Muscoda Gun Club jackets. We loaded our bikes with gear in front of the hotel and met two other guests, a couple in their fifties who were touring by bicycle. They wore safety-orange vests, safety bike helmets, safety flags on fiberglass poles, safety reflector stripes on their packs, pedals and spokes, and little rear-view mirrors attached to their helmets. Nice folks, but a little too safe for my tastes.

A few hours up the river we found Taliesin, the beautiful home of the Frank Lloyd Wright foundation, just outside of Spring Green. We stopped to visit Bill Logue, an old friend of mine who works for the foundation, and he gave us a tour of the buildings and grounds, showing us some of the new architectural works-inprogress, the most spectacular being a mountain-top home for the daughter of the Shah of Iran. We had lunch at the Spring Green, a Wright-designed restaurant overlooking the Wisconsin River, then left on our last leg of the trip, the 30 miles home to Madison. We were home just at sundown.

We cleaned up and went out for a celebratory pizza, rehashing our trip and doing some calculations. The ride had been exactly 303 miles long, over four days. The Honda used 1.8 gallons of leaded regular or premium, depending on what was available, which is 168.3 mpg, at a cost of $1.13. With over 6000 miles on the original engine, the Honda used no discernible amount of oil—the dipstick level was constant throughout the trip. John ate about $4 worth of granola bars while riding, plus a peach and three apples. There were no malfunctions of any kind on either machine.

In 15 years of riding and touring on all kinds of bikes, this was my favorite trip. It was a microcosm tour, measured in time rather than distance. Two days from home, the Mississippi River felt as far away from home as Denver or Montreal had on other trips with faster motorcycles. The pace was slow and enjoyable, largely over roads and through towns we had never seen before, though all were within a one-day drive by car. The natives spoke English, or some dialect thereof, and our currency was accepted everywhere. Best of all, we beat our postcards home, thus receiving news of our progress while it was still fresh and exciting.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue