UP FRONT

Ride the s.o.b

David Edwards

IT WAS A VIRTUOSO PERFORMANCE BY any standard. I’d ridden my flat-tracker Yamaha Twin the 30 miles up to Jerry Greer’s Indian Engineering to check on the progress of my 1940 Indian Sport Scout. Greer and company are transforming it from an out-to-seed racebike into a post-WWII bobjob, stripped-down precursor to the radical choppers of the 1960s and ’70s. One of the country’s top Indian restorers, Greer, among other things, is an exflat-track racer. He took one look at my Roberts-replica XS, said wistfully, “Boy, I put in a lot of laps on those,” and asked if he might take a spin on it.

After a cautionary sojourn through the gears, he returned, mumbled something about light flywheel effect, pointed the bike back out toward the street-then proceeded to goose the throttle, dump the clutch and paint a 15-foot black stripe with the rear Pirelli MT53. Roaring back into the parking lot a few minutes later, Greer casually pitched the Yamaha sideways in a nice second-gear powerslide, cut the motor and coasted to a stop beside me. Not bad for a 52-year-old guy in T-shirt and no helmet. It’s not for nothing that Greer has the words “Ride the Son of a Bitch or Sell it to Somebody Who Will” screened onto the sleeves of his shop T-shirts.

“Hey, thanks for letting me slap a leg over your scooter,” he said, all smiles.

I knew how he felt.

Technically, a large part of my job involves riding other people’s motorcycles. Eleven years ago, the new guy at Cycle News, I was assigned my first road-test bike, a Kawasaki KZ1000R Eddie Lawson Replica. Apparently the editor reckoned that my two years of riding a Yamaha Seca 650 on the mostly straight roads of north Texas qualified me to pass judgment on this lime-green blunderbuss, a rolling tribute to Steady Eddie’s 1981 AMA Superbike championship. It was fast, had shocks so stiff as to be suitable for carrier landings, and came stock with a Kerker 4-into-l that delivered a positively righteous exhaust note-the only way this thing got past government sound meters was by gross negligence or a bribe of NYPD proportions.

Well, I managed to keep the ELR out of the shrubbery; I even impressed the rest of the staff when I came in one day with scrape marks on the Kawi’s header pipes. I didn’t have the heart to tell them the damage wasn’t really a result of my cornering prowess-more a consequence of misjudging a particularly alpine speed bump.

A year later, I was hired away by Cycle World, where I’ve been for the past decade. During those 10 years, I’ve ridden just about every new production motorcycle built, as well as a fair smattering of racebikes, customs and classics-by loose estimate, some 1000 bikes in all. (Yes, it is the best job in the world; no, you can’t have it.)

The most memorable ride? Probably the laps I did at Laguna Seca aboard Wayne Rainey’s world championship Yamaha YZR500 in 1990. I’ve ridden Superbikes, endurance racers, BoTT champions, even Scotty Parker’s XR750, but nothing took my breath away like this 160-horsepower, twostroke V-Four. It’s the only racebike that I felt totally inept on, a feeling not helped by having Rainey, Eddie Lawson and team manager Kenny Robertsa group that would eventually total 11 world titles-on pit wall watching my ham-fisted efforts at keeping the YZR’s front wheel in some semblance of contact with Laguna’s tarmac. Sort of like having Olivier, Burton and O’Toole sit in review of your first read-through of Hamlet’s soliloquy, or unpacking your sax in front of Bird, Coltrane and Getz.

After 10 laps, I pulled in, faceshield fogged, mind reeling from the sheer effort it takes to keep a modern GP bike between the white lines. Roberts approached, got real close to my helmet and said softly, “Now you see why I don’t ride ’em anymore.” Definitely a highlight page in the ol’ mental scrapbook.

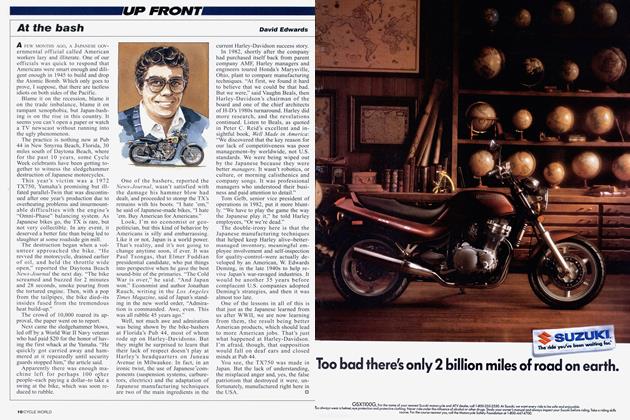

This month’s coverbike is another. Honda’s NR750 was a sensation when announced two years ago, a scarletred, carbon-fiber-clad beauty intended as a street-legal souvenir of Honda’s noble-if ill-fated-effort to take on the GP two-strokes with an oval-piston four-stroke. Originally, up to 700 were scheduled to be hand-built at a rate of three per day before production ceased forever on October 21, 1992. For reasons known only to the guiding lights at Honda in Japan, the company refused to divulge to Cycle World the exact number of NRs built-perhaps the market for $60,000 oval-piston neo-classics wasn’t as extensive as originally thought.

Anyway, as you can read starting on page 30, we persuaded the owner of the sole stateside NR to let us test his bike, though the contractual hoops we had to jump through bordered on the ridiculous-such as having a handler with the bike at all times.

This brought to mind the 1938 Brough Superior SSI00 I rode three years ago. Owned by Art and Bob Bishop, father and son, the Brough, one of 400 built, was worth an estimated $70,000 and had just received a rims-up restoration by a noted English expert. It was perfect. Yet Bob had no qualms about booting the Brough out the back of his pickup, showing me the starting drill, then turning me loose. “See you back at the cafe in a couple of hours,” was his parting comment, “have a good time.”

During my morning’s ride, I managed to overcook the ineffectual rear brake to the point that the drum’s freshly applied coat of gloss-black paint developed a series of cracks. I apologized for riding the 53-year-old beast with such elan, but Bob wasn’t concerned. “Hey, it was meant to be ridden hard,” he said, and refused to even discuss Cycle World paying for a rear-hub respray.

Honda NR750 and Brough SSI00. Motorcycles for the ages—and I may be the only person in the world who’s ridden both.

Guess which one I enjoyed more.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1994 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

August 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1994 -

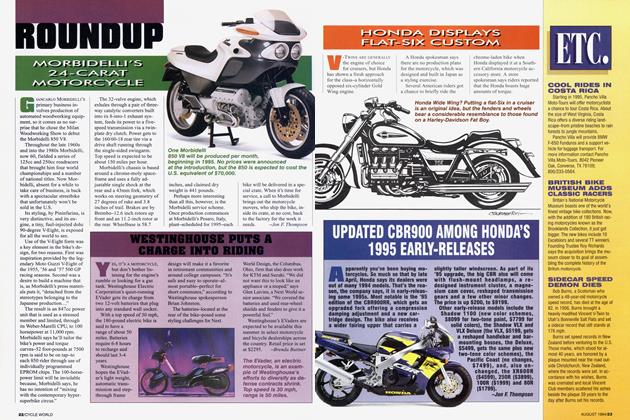

Roundup

RoundupMorbidelli's 24-Carat Motorcycle

August 1994 By Jon F. Thompson -

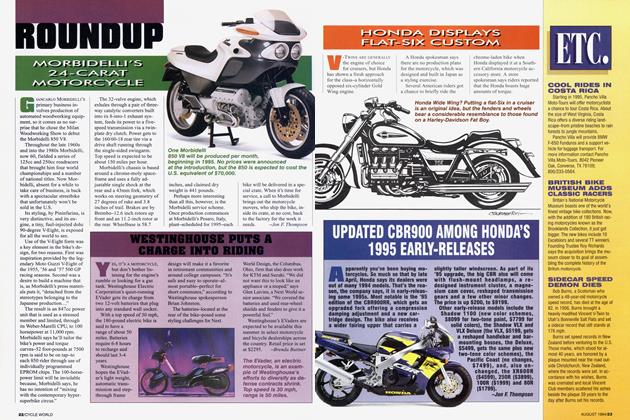

Roundup

RoundupWestinghouse Puts A Charge Into Riding

August 1994 By Brenda Buttner -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Displays Flat-Six Custom

August 1994