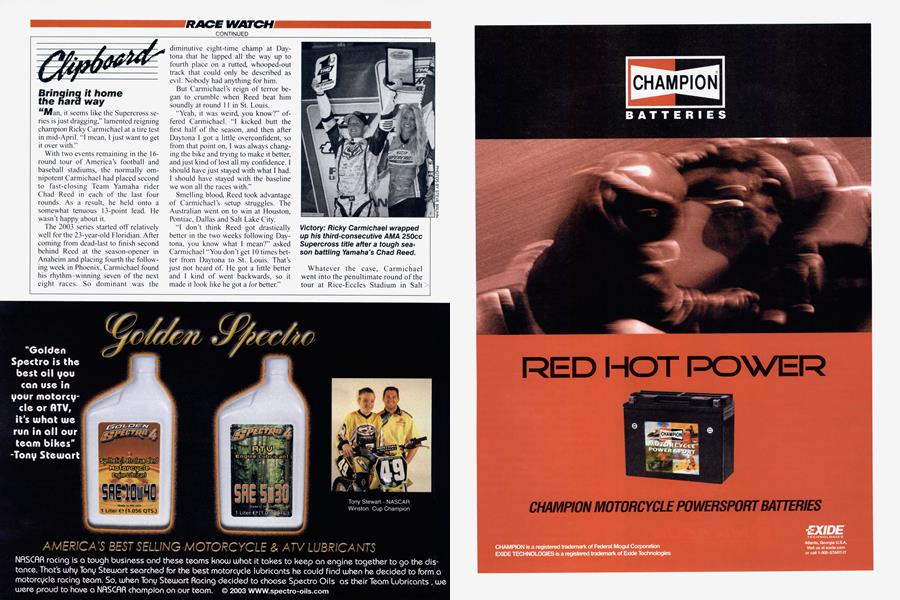

Bringinq it home the hard way

RACE WATCH

Clipboard

"Man, it seems like the Supercross series is just dragging,” lamented reigning champion Ricky Carmichael at a tire test in mid-April. “I mean, I just want to get it over with.”

With two events remaining in the 16round tour of Americas football and baseball stadiums, the normally omnipotent Carmichael had placed second to fast-closing Team Yamaha rider Chad Reed in each of the last four rounds. As a result, he held onto a somewhat tenuous 13-point lead. He wasn’t happy about it.

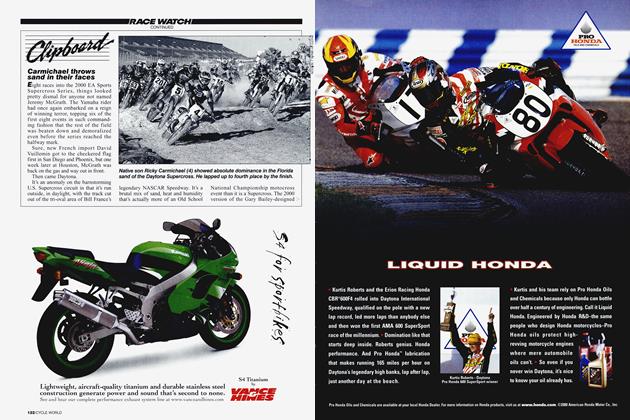

The 2003 series started off relatively well for the 23-year-old Floridian. After coming from dead-last to finish second behind Reed at the season-opener in Anaheim and placing fourth the following week in Phoenix, Carmichael found his rhythm-winning seven of the next eight races. So dominant was the diminutive eight-time champ at Daytona that he lapped all the way up to fourth place on a rutted, whooped-out track that could only be described as evil. Nobody had anything for him.

But Carmichael’s reign of terror began to crumble when Reed beat him soundly at round 11 in St. Louis.

“Yeah, it was weird, you know?” offered Carmichael. “I kicked butt the first half of the season, and then after Daytona 1 got a little overconfident, so from that point on, I was always changing the bike and trying to make it better, and just kind of lost all my confidence. I should have just stayed with what I had. I should have stayed with the baseline we won all the races with.”

Smelling blood, Reed took advantage of Carmichael’s setup struggles. The Australian went on to win at Houston, Pontiac, Dallas and Salt Lake City.

“I don’t think Reed got drastically better in the two weeks following Daytona, you know what I mean?” asked Carmichael “You don’t get 10 times better from Daytona to St. Louis. That’s just not heard of. He got a little better and I kind of went backwards, so it made it look like he got a lot better.”

Whatever the case, Carmichael went into the penultimate round of the tour at Rice-Eccles Stadium in Salt > Lake City with just 13 points on Reed. And although he got caught up in a few on-track altercations with Reed and his Yamaha teammate Tim Ferry, Carmichael managed to cross the finish line in second for the fifth-consecutivc race. With just one round remaining in Las Vegas and a slim 10-point lead on his adversary in blue, Carmichael simply wanted the curtain to drop on his season.

“The main thing was that I knew 1 could win the championship, so it was like, ‘Okay, let’s just go ahead and get this over with,” explained Carmichael. “It’s like when you have a 20-second lead and you know you’re going to win. Go ahead and throw the flag!”

When the checkered flag was waved in sold-out Sam Boyd Stadium, once again it was Reed over Carmichael with the latter’s Honda teammate Ernesto Fonseca taking his sixth-straight thirdplace finish. For the third time in three years, Ricky Carmichael, by 7 points, had clinched the SX title.

Although he put up a valiant fight-winning eight of 15 races-Rced was understandably disappointed to lose the title by such a slim margin.

“I do feel bummed,” he said. “Supercross is what I love and what I really > Paolo Flammini was feeling over the winter. Since 1988, Flammini's babythe World Superbike Series-had gone from strength to strength. Grown with out getting too big for its boots. Stayed friendly and entertaining while still be ing slick and shiny enough to be taken seriously. Without it, it's safe to say, there'd probably be no Ducati. If there hadn't been a Ducati renaissance, would Aprilia be building big bikes? Would any of the European bike manufacturers be feeling as cocky as they currently do? It's hard to say for sure, but I don't think so. Flammini's series has also pro duced a few 24-carat heroes. How does a roll call of Merkel, Polen, Fogarty, Bayliss and Edwards sound for starters? But that's history. This is 2003, and when Paolo sent out his latest batch of invites he only received a handful of RSVPs. Few would argue World Superbike is looking a bit threadbare. At the end of last season, the Honda and Kawasaki factory-supported teams fol lowed Yamaha out of the WSB paddock. The top talent didn't hang around, ei ther. Current and former champions Cohn Edwards and Troy Bayliss were sucked out of their motorhomes by the

World Super death watch?

Ever held a party and no one turned up? Neither have I, but it must produce emotions somewhat similar to what

want to win, so I kind of feel I got beat at my own game. Now I have to re group, reset the odometer and kick ass next year." Eric Johnson MotoGP tornado, and fan favorite “Nitro” Noriyuki Haga went with them.

Who’s left? Not surprisingly, Ducati has been honorable, supporting WSB with the Fila factory squad and, as usual, throwing last year’s bikes and parts at favored privateer teams. The Coronabacked Alstare Suzuki GSX-R1000 is

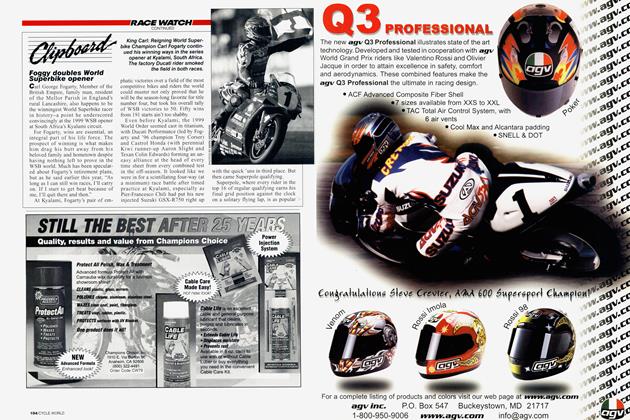

the only factory Japanese bike on the grid. If it weren't for the dramatic return of WSB’s favorite son, the paddock would have looked something akin to an Amish Motor Show. Luckily for everyone with a soft spot for or a vested interest in the series, Carl Fogarty and the team he spearheads, Foggy Petronas

Racing, have arrived just in time to help WSB through a very lean year.

At Valencia, Spain, the first round, the surgeon-smock-green team and their gorgeous Triples drew the lion’s share of media and fan attention. They raised the whole mood of the paddock, and gave the organizers enough pride to allow them to show their faces in public. What would it have been like without Fogarty’s team? Miserable. The series would finally have deteriorated into the “Ducati Cup” detractors have incorrectly labeled it for years. But with Fogarty, there was something to talk about.

The bikes of ex-champion Troy Corser and his British teammate James Haydon spat 3-foot flames from their funky inconel-and-carbon underscat exhausts. They cooked the front fairings of midfield runners and mesmerized TV cameramen-all good for the new team. Corser even put the bike on the first row at its first-ever race. It’s a depleted field, but respect is still due.

Meanwhile, last year’s third-best rider, Neil Hodgson, has moved to the fac-

tory Ducati team from the private HM Plant squad and remains unbeaten four rounds into the series. Is he discouraged by the lack of competition? Er... no. On the other 999 is Ruben Xaus. The gangly Spaniard spends timed practice sessions demolishing more Ducatis than is really decent, but in races, he’s been putting enough pressure on Hodgson to add a little excitement to the sharp end of the proceedings.

So who is benefiting from the WSB paddock exodus? Well, Fogarty’s team isn’t getting the demoralizing maulings that would’ve been inflicted by a fuller grid. Gregorio Lavilla has stuck his restricted Corona GSX-R1000 (stupid rule, Paolo, dump the intake restrictors for next season, please) on the podium, and that’s got to encourage Yamaha and Honda to return with trick YZF-R1 and CBR954RR racers next year, just as they said they might.

The 999s arc running away with it; never has picking a champ been such a safe bet. But there’s still good racing among those trying to get that last podium spot, with four di flerent riders taking third in the first four races. Hardmen like Pier Francesco Chili and Chris

Walker arc hanging it out, stuffing it under each other and riding like guys whose mortgages depend on good finishes. Watching from home, another WSB refugee, Ben Bostrom, has said he’s impressed. Now, he’s contesting the more competitive AMA Superbike Championship and knows it. Maybe, secretly, he’s wishing he was battling Hodgson for that first world crown.

But don’t believe the naysayers. World Superbike isn’t dead. It might be on a drip, but there’s still some life left in it yet. Gary Inman

New life for NHRA Pro Stock

To paraphrase Mark Twain, it appears that the demise of the NHRA Pro Stock Bike class has been greatly exaggerated. After a tumultuous off-season appeared to leave two of the most popular riders, Angelle Savoie and Matt Hines, on the sidelines and several other teams fighting to stay financially afloat, the class has undergone a transformation and emerged better, stronger and more popular than ever.

While it’s true that a lack of sponsorship forced Vance & Hines to park its Suzuki team, leaving Matt without a ride for the first time since 1996, the move may well have been a blessing in disguise. During his sabbatical, Hines, an underrated tuner, assisted in the development of the Vance & Hines Screamin’ Eagle Harley-Davidson VRods, and has helped those bikes become a force on the NHRA tour.

At the most recent event in Atlanta, G.T. Tonglet and Matt’s younger brother Andrew both not only qualified in the top half of the 16-bike field but also reached the quarter-final round of eliminations. Hines’ best run of 7.17 seconds was a scant hundredth of a second off the pace set by eventual race winner Geno Scali.

The continued success of the V-Rod might well be the key to the long-term survival of the Pro Stock Bike class at the national level, as other manufacturers are said to be looking to enter the class.

Said team owner Terry Vance, “Right now, Harley-Davidson has 50 percent of the big-bike and cruiser market, so other factories would be foolish not to look > at what it’s doing. I’ve said from the start that once we got our V-Rods to be competitive, the other factories would jump in, and I still believe it.”

The NHRA’s Pro Stock Bike class might not ever reach the level of the AMA Superbike or Supercross series, where riders compete for multimillion dollar contracts aboard factory-backed machines, but it’s obvious that the landscape is changing.

“I could see the day where there are six or seven factory-level riders,” said Vance. “There are three right now, which doesn’t sound like a lot, but two years ago, there were none. We’re clearly moving in the right direction.”

And what about Savoie, who is easily the sport’s most recognizable rider? Nobody figured that someone so talented would remain on the sidelines for long, and less than 48 hours after her shocking departure from George Bryce’s Star Team, the three-time and reigning NHRA champ resurfaced as a member of Antron Brown’s Team 23 outfit. Savoie won the season’s first two races and is currently challenging for her fourth title.

Bryce also did not remain on the sidelines for long. After folding his own team, the former rider-turned-crew chief and engine builder is working as a crew chief for Reggie Showers and building engines for the upstart Area 51 team, which features mega-talented two-time AMA Prostar champ Fred Collis as its rider.

Despite lingering economic con cerns, Pro Stock Bike is holding its own. Each of the first three events fea tured more than 30 riders competing for a spot in the 16-bike field, and with the emergence of the Harley V-Rods and a Muzzy Kawasaki based on the popular ZX-12 model, the class that was once dominated by Savoie and Matt Hines has become far less predictable, and therefore much more entertaining than ever before. -Kevin McKenna

George Roeder, 1936-2003

When George Roeder earned his AMA Pro license in the early 1960s, the press quickly dubbed him-"The Flying Farmer"-which was catchy and also fair, in that farming had been his job.

Roeder, who died of a heart attack this past May at age 66, never lost the cheerful, earthy gruffness that comes from working with non-negotiable nature. But to rivals and the fans who saw National Number 94 in action, Roeder was known as a stylist.

Back then, back when rear wheels were rigidly mounted and brakes were banned, Roeder was a master of the slide, pitching his temperamental Harley Davidson KR into turns so deffly that the watcher never knew how tou2h it was.

He was signed by the H-D factory, and won eight GNC races-three miles and five half-miles. In case that sounds specialized, Roeder was equally at home on pavement: The AMA series then had roadraces as well as dirt, and Roeder was on the podium at Daytona four times. He was twice runner-up for the national title, losing by 1 point (1 point!) to Dick Mann in 1963 and to Gary Nixon, by a larger margin, in 1967.

Roeder’s last GNC win was on the Sacramento Mile in 1967. One can make a case for The Flying Farmer being the fastest rider to never win the AMA title, as at the end of that season, hampered by injury and with a family to raise, Roeder retired from the Pro ranks.

But that was only the part of his life that got him into the Motorcycle Flail of Fame.

Roeder was a family man. The entire family went to the races and all the kids— girls as well as boys-raced. Two sons, Jess and Geo (short for George II, but always pronounced as “Joe”) have National Numbers 66 and 94, respectively.

Roeder went back to the farm after retirement, but at the urging of wife Jessie at home and John Davidson in Milwaukee, he opened a Harley dealership in his hometown of Monroeville, Ohio.

This was in 1972, the worst of all times to go into the American-bike business. And it was small, literally in a barn, where Roeder assembled new bikes he’d hauled from the factory in the farm’s truck, and it was surely the only business that’s riskier than farming.

Roeder officially retired in 1991, with son Will in charge. It’s just as safe to say there’s a happy ending-check H-D sales-and the family is about to open a second dealership in nearby Sandusky.

Roeder is survived by his wife, their three sons and their daughter, Kami.

Allan Girdler

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontIssue No. 500

August 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRiding the Cheyenne Breaks

August 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPressing Matters

August 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Department

DepartmentHotshots

August 2003 -

Roundup

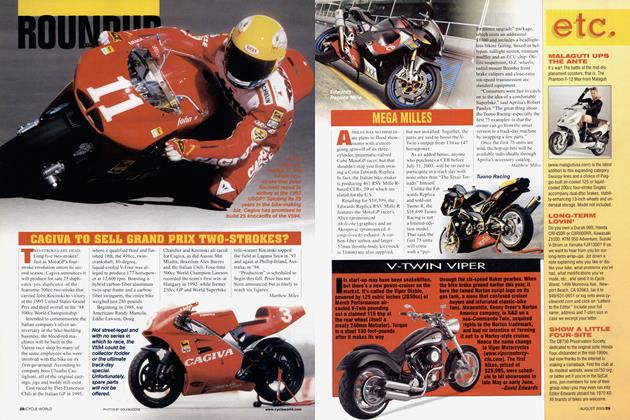

RoundupCagiva To Sell Grand Prix Two-Strokes?

August 2003 By Matthew Miles -

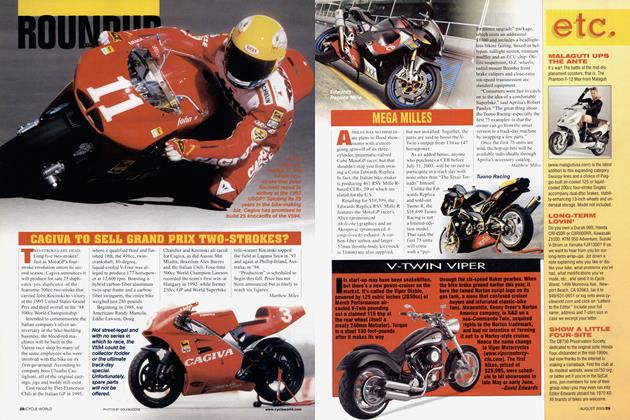

Roundup

RoundupMega Milles

August 2003