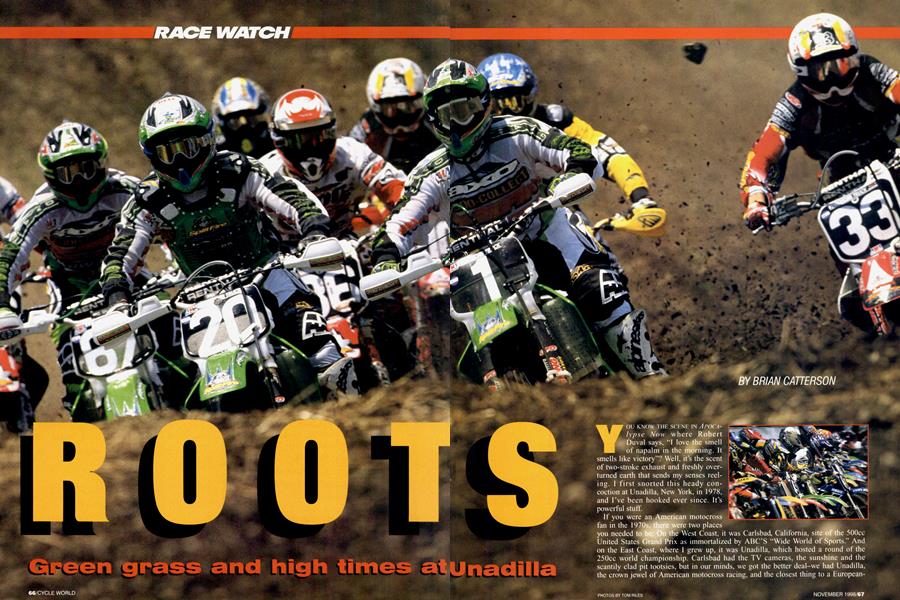

ROOTS

Green grass and high times at Unadilla

RACE WATCH

BRIAN CATTERSON

YOU KNOW THE SCENE IN APOCAlypse Now where Robert Duval says, “I love the smell of napalm in the morning. It smells like victory”? Well, it’s the scent of two-stroke exhaust and freshly overturned earth that sends my senses reeling. I first snorted this heady concoction at Unadilla, New York, in 1978, and I’ve been hooked ever since. It’s powerful stuff.

If you were an American motocross fan in the 1970s, there were two places

you needed to be: On the West Coast, it was Carlsbad, California, site of the 500cc United States Grand Prix as immortalized by ABCS “Wide World of Sports.” And on the East Coast, where I grew up, it was Unadilla, which hosted a round of the 250cc world championship. Carlsbad had the TV cameras, the sunshine and the scantily clad pit tootsies, but in our minds, we got the better deal-we had Unadilla, the crown jewel of American motocross racing, and the closest thing to a Europeanstyle circuit this side of the Atlantic.

1 first visited Unadilla at the tender age of 16 when I talked my father into a little detour on the way home from summer vacation. Through a fortunate coincidence, the inaugural 250cc USGP was being held the same weekend our family would be driving home from Loon Lake to Long Island, so it really was on the way. And because I was a card-carrying, red-white-andblue jersey-wearing Honda Elsinore owner, it was my sworn duty to attend.

My dad, younger brothers and sister all enjoyed the outing okay, but my mother was flabbergasted. You see, Unadilla drew a rowdy crowd. Not rowdy in the outlawbiker sense, where a guy could get knifed just by looking at the wrong girl, but rowdy in the beer-guzzlin’, dope-smokin’, wild-party

sense. It’s one thing for some belligerent cretin to shout “Show your tits!” to your girlfriend but it’s quite another when the breasts in question belong to dear old Mom!

And while I admit I'll never forget the drunk who passed out next to the track fence and woke up buried in a berm, what I remember most is the racing. After a decade spent studying under the European masters (which sounds a lot better than saying “getting trounced by”), America’s motocrossers were eager to prove they'd learned their lessons well (actually, they wanted to kick some Continental ass). And prove it they did: The Yanks shut out the “Euro-peons,” as Jimmy Ellis and Bob Hannah won the two motos while Marty Tripes scored the overall victory with a pair of seconds. Sweet revenge! Thus began a period in which America became a dominant force in international racing, culminating in our boys winning the prestigious Motocross des Nations 13 consecutive times.

This year, on the 20th anniversary of my first visit, I returned to Unadilla. A pilgrimage, if you will. Though I’d attended the races religiously from 1978-84, I’d not been back since moving to California that latter year. And I

often wondered: Had Unadilla withstood the test of time? Was there still a place for a natural-terrain motocross course in today’s Supercrossobsessed world?

The answer, happily, is yes. Though the race is now a round of the AMA Mazda Truck National Championship rather than a GP. for all intents and purposes, Unadilla is unchanged. It’s still a relatively low-key event, attended almost exclusively by racers and fans. The only hints that there’s a motocross race in the area are the many “For Sale” signs hung on the locals’ motorcycles. It’s as if everyone who’s

ever owned a bike simultaneously decided to sell it—or more accurately, seized the one opportunity each year that a passerby might happen to see it. After a pleasant hour’s drive through scenic farm country, I arrive at the racetrack, announced by a big, white barn plastered with sponsors’ banners.

The Unadilla Valley Sports Center is located in a remote area of upstate New York, on two-lane State Route 8, about equidistant between Binghamton and Utica. The region looks a lot like Europe, a fact that hasn’t been lost on the locals-the nearest town is called New Berlin, and Paris and Rome are just down the road. There’s also a place called Mexico, where there’s another motocross track, and the nearby Broome-Tioga Sports Center will host an AMA national of its own in just six weeks. Clearly, this is motocross country.

What sets Unadilla apart from most other American MX tracks is its status as a pure, natural-terrain course. Nearly 30 years ago,

promoter Ward Robinson and British motocrosser-turned-trials-star Mick Andrews laid out the track in a rolling, green field bisected by a gorge. The rugged topography allowed the cre ation of two notable track features: The first is "Gravity Cavity," a 50foot-deep, V-shaped G-out that the rid ers freefall into, hit bottom and then shoot up the opposite slope to gain big, big air-more than 30 feet if the scale on the Copenhagen Air Chal lenge banner hanging from the speaker tower can be trusted. And the second, affectionately called “Screw-U,” is a left-hand hairpin at the bottom of a hill so steep, it isn’t even used during Saturday practice for fear of erosion.

So difficult is the climb that officials have been known to re-route the course mid-race if it gets too muddy.

Factor in obstacles such as off-camber sidehills, treacherous top-gear straightaways, bumps and jumps galore (all made by Mother Nature, not John Deere), plus Unadilla’s infamous baseball-sized rocks, and you’ve got a track that punishes both machine and man. You won’t find a truer test of physical conditioning than running two 30-minute-plus-two-lap motos around here in summertime heat and humidity. A better name for the place might be “Unakilla.”

My first look at the track Saturday morning leaves me with mixed emotions. It looks smaller than I remember-like revisiting Disneyland as an adult and realizing that the Matterhorn isn’t really a snow-capped peak. Come raceday, however, my per> spective changes. The presence of 13,000 race fans makes the place look bigger, an ocean of colors versus a sea of green.

Also, while the track layout is identical, the racing surface has changed. Where in years past there was nothing but tall grass between the fences before practice started, this year there’s well-churned dirt, legacy of the 1300 amateur racers who did battle (on an abbreviated course) before

the pros hit the track Saturday afternoon. As a result, the soil isn’t as loamy as it used to

be-and it’s a lot rockier. To ward off the potentially damaging roost, the racers don chest protectors and nose guards, while the mechanics outfit the bikes with hand guards, pipe guards and disc guards, as well as heavy-duty tubes to prevent flat tires.

Breaking from tradition this year, bulldozers and water trucks lap the track between practice and the races in an effort to smooth the bumps and avoid a repeat of last year’s uncharacteristic dust-fest. The result is nearperfect track conditions-a far cry from the last time I was here.

One MX great who remembers the not-so-good old days is “Jammin”’ Jimmy Weinert, an area resident who serves as color commentator over the track’s p.a. system. According to him, grooming the track isn’t necessarily a bad thing. “They never used to prepare it for us, so the grass would grow, and every time we came here we had to beat down the grass. And the bumps got bigger...and bigger... and bigger. They were so big, in fact, it wasn’t any fun.”

Between the well-manicured track and the 12 inches of suspension travel their bikes possess, today’s pro riders make lapping Unadilla look easy. The 125s are particularly impressive, as the production-based bikes power up hills in fourth gear that in the old days even the works 500s struggled up in second. But by the end of practice, the track is its usual whooped-out self, and not everyone appreciates that.

“I don’t like this track,” says Ricky Carmichael, the 18-year-old Pro Circuit Kawasaki phenom who leads the 125cc title chase. “It’s too fast, too wide-open and there are too many rocks.”

Team Yamaha’s Doug Henry takes the opposing view. “I love coming here,” says the 28-year-old 250cc points leader. “All my friends come here. It’s definitely the roughest track on the circuit, and there’s a lot of history-like the Daytona Supercross.”

As always, the racing is epic. Team Kawasaki is the big winner, as defending champions Carmichael and Jeff Emig score the overall victories following second-moto wins. But neither has it easy: In the first 125cc moto, Carmichael falls victim to Team Primal Impulse Suzuki’s Robbie Reynard, whose fast, fluid riding is a sight to behold. The Oklahoma native gets a lousy start-14th the first time past the mechanics’ signaling area-but he puts his head down and charges to the front, sailing past Carmichael like he’s a common backmarker.

Unfortunately, Reynard gets another lousy start in the second moto, and then experiences stomach cramps while reeling in the leaders. Still, his third-place moto finish is good enough for second overall, his best result of the season.

Carmichael, meanwhile, runs his own race out front, displaying the speed and showmanship that have made him the talk of the paddock. He sails higher and farther over the jumps than all but the best 250 riders, and performs amazing acrobatics-some as part of his technique, most for show. His performance is, however, tainted by an early altercation with rival John Dowd that sends the latter tumbling over a haybale. Though it’s a pure racing accident caused by Carmichael’s Kawasaki bucking wide into Dowd’s Yamaha, it looks bad for the kid-and he knows it. “I probably lost some fans today,” he says afterward, looking glum. Not to worry: He’s got plenty to spare.

Emig, meanwhile, is on the comeback trail after a back injury forced him to sit out the latter half of the Supercross season. He won the previous outdoor national at Red Bud Track & Trail in Michigan, but on the following Thursday he hurt his shoulder when he fell while practicing at Glen Helen Raceway in California. To make matters worse, Emig gets knocked down in the first moto at Unadilla, and remounts to finish a distant fourth. His chances of capturing the overall victory look slim, but first-moto winner Kevin Windham crashes his factory Yamaha hard while giving chase in the second moto, leaving Emig alone out front. Smooth-riding “Jeffro” makes it look easy as he holds off a late-moto charge from Team Suzuki’s Larry Ward to win both the moto and the overall.

The crowd goes crazy during the late-race battle, screaming and whipping their T-shirts as their heroes flash past. But while the fans are as rabid as ever, they’re much better behaved than back in the day. Gone are the rowdies who packed the Gravity Cavity, lobbed beer bottles at each other and shouted, “The other side sucks!” And not one porta-potty was damaged-a far cry from the year my high-school buddy Bob Schaefer and 1 hitchhiked to the races to find smoldering embers where the johns used to be-not to mention a few tents and what looked to be a late-model Cadillac.

The only throwback I encounter is a guy selling stickers reading “Unafriggindilla, The Woodstock of Motocross” (only they don’t say “friggin”). Price: $1, or free if you > SYT. When last I see him, he’s being chastised by two young moms who don’t appreciate him using that sort of language in front of their kids. It really has become a family affair.

Emig is especially appreciative of the fans’ support, and thanks them during his post-race interview. “You guys are great!” he says over the p.a. system. “It made me feel really good to hear everyone cheering.”

A round of the Women's Motocross Championship (won by Shelly Kahn) follows the 250s, and as the last motorcycle returns to the pits, the track crew opens the

gates. The excited fans flood the circuit, following the same lines their heroes did earlier. I join in their masses, and find myself swept to the base of the announcer’s tower, where the victors eagerly accept their trophies. Almost an hour has passed since the second 250cc moto, yet the riders still appear drained, and it takes every last ounce of their strength to hoist the victory champagne. With fumbling fingers, they pop the corks and spray the bubbly, and as the trophy queen takes a bath, the announcer talks of next year. Back in the pits, the mechanics already are working on the bikes, hosing off the Unadilla muck in preparation for next weekend’s series round at Kenworthy’s Farm in Ohio, a flat-as-a-pancake, jump-infested track that the riders jokingly refer to as “the 17th round of the Supercross series.” But while the show must go on, for myself and the rest of the Unadilla fans, the main event has already taken place.

In his book, The Art of Motocross, racing legend Jeff Smith describes the sport as, “Mechanized steeplechasingan especially exciting branch of motorcycle sport in which races take place over several laps of a roughcountry circuit perhaps a mile and a half in length. The circuit could (and usually does) embrace steep hills and descents, ditches, sandpits, watersplashes and various other obstacles.”

Notice that nowhere does he say anything about stadiums, $10 parking spots or fireworks. Supercross is great, but it’s not really motocross. And it’s definitely not Unadilla. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

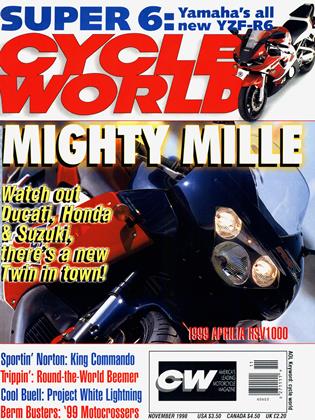

Up Front

Up FrontUjm Redux?

November 1998 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBuying A Shadow

November 1998 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCOut of Bounds

November 1998 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1998 -

Roundup

RoundupHarley To Buy Ktm?

November 1998 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupCagiva/ducati Divorce

November 1998 By Brian Catterson