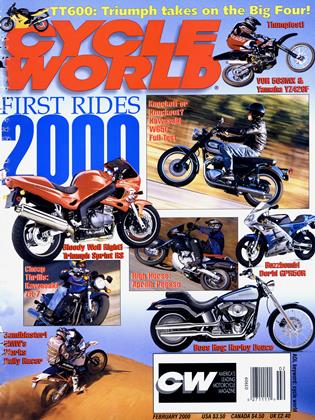

Triumph Sprint RS

FIRST RIDERS 2000

Finally worthy of its name

CYCLE WORLD HAS HAD A long love affair with the Triumph Sprint 900. The original version was named Best

Open Streetbike in our 1995 Ten Best awards, and the second-generation Sprint ST copped last year’s inaugural Best Sport-Touring Bike award after it topped our “GT Experience” shootout (CW, March, 1999). Neither, however, really lived up to its name. Softly suspended and laden with optional hard luggage, they excelled at long-distance running, not sprinting. The faster the pace, the worse they performed.

The new-for-2000 Sprint RS rectifies that situation. Essentially an ST with a smaller half-fairing and accompanying reduction in weight (a claimed 438 pounds dry versus 456, not including saddlebags), the RS feels totally transformed. It’s as though a great burden has been lifted off the bike’s shoulders. Which in a way, it has.

Like the ST, the RS is powered by a retuned version of the mighty 955i Daytona’s liquid-cooled, dohc, 12-valve Triple. Steel cylinder liners and cast pistons are substituted for the Daytona’s coated aluminum and forged components, while reshaped camshafts and a reprogrammed Sagem engine-management system emphasize low-end and midrange power. Claimed

output for both Sprints is 108 horsepower at 9200 rpm, and 72 foot-pounds of torque at 6200 rpm.

You’d never guess that from the saddle, because the RS accelerates noticeably more briskly. Passing slower vehicles is exhilarating rather than intimidating, and you find yourself decelerating to the posted speed limit as you enter the freeway. Wheelies are a snap.

In sport-riding mode, the RS’s added acceleration effectively shortens straightaways, the engine’s distinctive, spine-tingling wail bouncing off canyon walls all the while. Then, having arrived at a turn, you’re able to brake deeper, lean over farther and carry more speed from the entrance to the exit. Cornering clearance isn’t an issue, thanks to the lack of fairing lowers and a muffler mounted higher than the ST’s two-positionadjustable setup even in its upper position. During our most spirited riding, we dragged only the footpegs, which touched down about the same time as our knee pucks.

But while the RS prefers to go fast, it is quite content to go slow. Lug the engine way down in the rev range, then pin the throttle, and it will only stumble for an instant before recovering and pulling smoothly all the way to redline. Well, maybe not “smoothly,” because the engine does vibrate quite a bit—far more than the fi'rstgeneration 1 nple in the Thunderbird Sport featured in this issue’s “Quick Ride,” for instance. The buzzing never really goes away, it just diminishes around 5500 rpm, which means you either need to speed in sixth gear or downshift to fifth to achieve the smoothest possible freeway ride.

Speaking of freeways, the RS’s Showa suspension lets it positively float over SoCal’s concrete superslab, and this, combined with exceptional stability and good wind protection, means the Sprint’s customary long-distance capabilities haven’t been compromised. And they can be further improved with the aid of Triumph’s comprehensive accessory line.

Not everything is perfect, however. While most appreciated the Triumph’s sporty looks, some scowled at the cheesy chrome ‘RS” graphics and the 3R900RRstyle “Honda holes” in the fairing sides. I he cockpit also met with some criticism, not because of the trick, YZF-R1-style digital speedo and white-faced analog tach, but because of the exposed wiring and generally unfinished look of the inner fairing.

While we’re in that neck of the woods, we’ll point out the RS’s two main flaws, both of which have to do with its hand controls. The clutch lever is awkwardly shaped, with a stiff pull, and the adjustable brake lever is too close to the handgrip even at its farthest setting. Furthermore, the brakes themselves lack feel and, to a lesser extent, stopping power. Different pad material would likely help.

If Triumph were to address those shortcomings, the Sprint RS would be just about perfect, and undoubtedly in the running for its third Ten Best award. Whoever coined the phrase “three’s a charm” must have been thinking of a Triumph Triple. —Brian Catterson