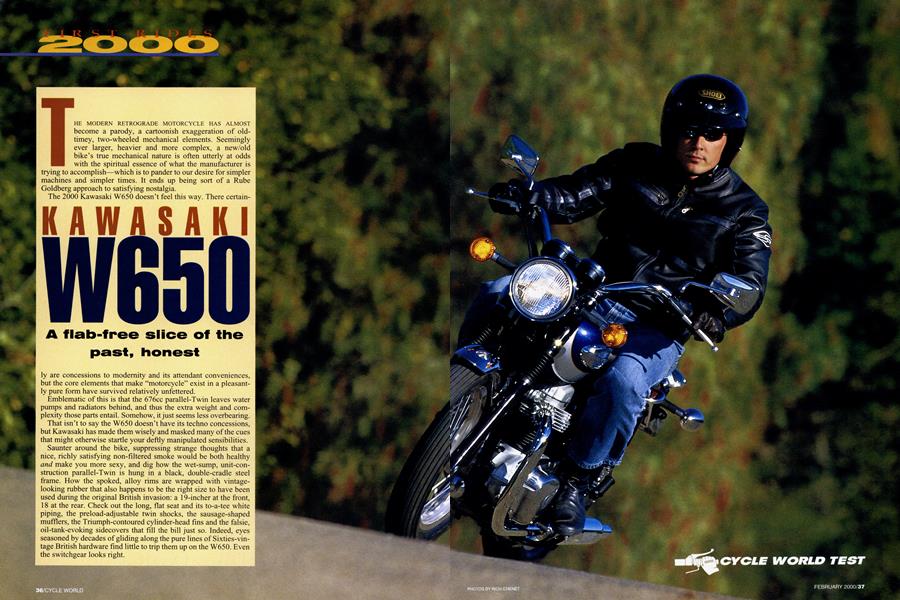

KAWASAKI W650

FIRST RIDERS 2000

A flab-tree slice of the past, honest

THE MODERN RETROGRADE MOTORCYCLE HAS ALMOST become a parody, a cartoonish exaggeration of old-timey, two-wheeled mechanical elements. Seemingly ever larger, heavier and more complex, a new/old bike’s true mechanical nature is often utterly at odds with the spiritual essence of what the manufacturer is trying to accomplish—which is to pander to our desire for simpler machines and simpler times. It ends up being sort of a Rube Goldberg approach to satisfying nostalgia.

The 2000 Kawasaki W650 doesn’t feel this way. There certain-

ly are concessions to modernity and its attendant conveniences, but the core elements that make “motorcycle” exist in a pleasantly pure form have survived relatively unfettered.

Emblematic of this is that the 676cc parallel-Twin leaves water pumps and radiators behind, and thus the extra weight and complexity those parts entail. Somehow, it just seems less overbearing.

That isn’t to say the W650 doesn’t have its techno concessions, but Kawasaki has made them wisely and masked many of the cues that might otherwise startle your deftly manipulated sensibilities.

Saunter around the bike, suppressing strange thoughts that a nice, richly satisfying non-filtered smoke would be both healthy and make you more sexy, and dig how the wet-sump, unit-construction parallel-Twin is hung in a black, double-cradle steel frame. How the spoked, alloy rims are wrapped with vintagelooking rubber that also happens to be the right size to have been used during the original British invasion: a 19-incher at the front, 18 at the rear. Check out the long, flat seat and its to-a-tee white piping, the preload-adjustable twin shocks, the sausage-shaped mufflers, the Triumph-contoured cylinder-head fins and the falsie, oil-tank-evoking sidecovers that fill the bill just so. Indeed, eyes seasoned by decades of gliding along the pure lines of Sixties-vintage British hardware find little to trip them up on the W650. Even the switchgear looks right.

CYCLE WORLD TEST

It led us to wonder what the W650 would be like side by side with a 1960s Triumph Bonneville. Luckily, we had an old Bonnie hanging upside-down from the ceiling of the men's room as part of our now-obsolete millennium sur vival kit. The resemblance is uncanny, our W650 sort of a Triumph, plus 5 percent—it really is a larger motorcycle than an old ’un, but the proportions are right. Aside from size, the two bikes hummed in near-perfect aesthetic harmony, right down to the rubber fork gaiters and handlebar bend and rubber pads on the tank (come to think of it, those, like the tank badges, are a little too too).

All the cool, up-to-date features that have made motorcycles so trouble-free and good-running these days are, however, included. Digital ignition and a pair of (somewhat lean in the middle) Keihin CVK 34mm carbs mean using the kickstarter is novel entertainment, a little piece of kitsch that adds flavor without frustration. If you don’t feel like being entertained, hit the electric-starter button: It works every time! Techno-savvy four valves per cylinder pop in and out of stroky 72 x 83mm cylinders.

The signature piece of the powerplant is what excites those valves: a tower-shaft, bevel-gear-driven single-overhead cam. In many ways the bevel drive is just as unnecessary as the kickstarter, and certainly an added manufacturing expense. But it is no less crucial in establishing the bike’s personality.

For personality is one of the biggies with a motorcycle like this. Balance-shafted and rubber-mounted, the 360-degree parallel-Twin nonetheless exerts its character. Does it shake and tingle like an old Bonnie? Nope. Wouldn’t want it too, either. It’s got enough rhythmic boogie to let you know you’re riding a ProPer motorbike without punishing you for it. The sound emanating from the chromed pipes is good, if too muted by EPA regs (nothing the aftermarket can't fix). No surprise, really: Combustion is still combustion, even if it is digitally initiated. Power output isn’t phenomenal—there is a reason Kawasaki stopped making its W2SS BSA-copy of the '60s (see Adebar) and, like most other manufacturers who survived into the ’70s, started making inline-Fours. But the 43.6 horsepower and 37 foot-pounds of torque are quite enough for brisk, if not necksnapping motivation. It’s even okay two-up.

In fact, it is interesting to note that performance figures for the W650 are not unlike those CWgot from a Triumph Bonneville 650 in a 1971 test. The Kawasaki’s 14.05-second quarter-mile time was about two-tenths quicker, while the 0-60-mph figure was more than a half-second better. Even braking distances were similar, only a few feet apart for the 30-0 and 60-0 tests, despite the Kawi’s two-piston front disc going up against a double-leading-shoe drum. Maybe the Triumph’s 400 pounds helped it against the Kawasaki’s 451, although the real culprit here is the W650’s merely adequate brake hardware. Decent feel at the front, but suffice it to say that the no-piston, no-caliper drum at the rear isn’t, umm, overly grabby.

In practice, though, all the mechanical elements of the W650 combine to make it a pleasing platform on which to motor at a stately, pleasant pace through pastoral scenes. You can flog it at 85 mph, dodg ing bullets on urban free-

ways, but it just ain’t meant for it, and so it ain’t no fun.

Come to think of it, nothing is truly fun in that realm. Ton-up types will be pipped to know the Kawi is up to the task. Dial up six grand in the top of five slick-shifting gears and you’re there. Again, it isn’t outside the performance realm, but it is outside the pleasure realm.

Back it down to an indicated 65-70, and the midsize Twin thrums along nicely at 3700 rpm with a mild, friendly vibe though your various body/bike interfaces. Relaxed chassis geometry imparts a general stability, although at speed the retro-style ribbed front tire likes to follow rain grooves. The best fun is had off the superslab on meandering two-lanes. It is there that the bottomheavy nature of the W650’s chassis/engine package makes it as predicable as a pendulum while you swing it through the bends, trans clicked into whatever gear keeps the engine spinning above three grand. A torque curve flatter than the line on an AÍ Gore fun meter is the source of the unerring motive drive. Calling it a curve is, in fact, a disservice: Foot-pounds amazingly stay within 3 of peak from 1700 to 6500 rpm. You don’t sense a powerband because it simply happens while the engine is running.

The natural riding position is upright—best suited to 6 feet and under though it accommodates big people pretty well— with footpeg feelers the first things to touch down. Ground clearance is good, a nice side benefit of the not-a-birthingchair ergos. The 100 miles you get before reserve is just about the right range.

Push the pace hard on less-than-perfect pavement and the lightly damped suspension will get busy enough to unfurl your ascot, with a bit of dodge and weave in faster sweepers, no matter how smooth they may be. A streetwise brisk pace is entertaining, but you can obviously leave the knee pucks at home. Even if you did the right thing and made this bike into a cafe-racer with some low bars and a single seat, proper etiquette dictates using your toe-sliders, Hailwood-style.

What’s really odd about the chassis dynamics is how much fun this thing is to ride at very low speeds. You’ll find yourself showing off for your friends with tight flgure-8s in the parking lot, not wheelies, and lugging the flywheel-intensive, supertractable engine down to practically no revs—without negative consequence—instead of doing tire-smoking burnouts. You’ll ask your DMV representative: “Can I please take the riding test again?” Bike-magazine photo models will ask their photographers for just a few more passes, only to get in some extra impossibly easy, impossibly tight feet-up U-turns. The W650 seems as easy-steering and friendly to ride as a motorcycle can be.

When you get down to it, isn’t that really what you’re looking for in a nice standard-style machine? And while we have seen retro-Britbikes that have tried to fill this bill before—Honda’s GB500 Single pops to mind—they have tanked on the showroom floor. But the times they are achangin’ and may be just right for a little slice of flab-free retro. If there’s an old-timey bike out there that deserves to be bought, it’s this one. Triumph is working on its own new/old Bonneville. Well, it better be good. The W650 is an honest, neo-vintage motorcycle that’s simple fun to ride. Nothing dated about that.

KAWASAKI W650

$6499

EDITORS' NOTES

ALL THIS EFFORT, ALL THIS TIME SPENT trying to be as overweight and talented as Anthony Gobert. Eve got overweight wired, but talent...well, not a whole lot has changed over the years. So, while Goey keeps getting factory rides to blow, I just get another sore back and speeding ticket on my way to a hot date with a slice of pizza.

Em thinking it might be getting near time to drop the knee-dragging-roadracer pretense, at least on the way to work.

W650, maybe? Comfy, easygoing and dressed up in cool duds, it’s a nice place to spend some time when you’ve got nothing to prove. Sure, it’s got its own peculiar brand of pretense, but it’s sort of like Mike Meyers playing Austin Powers: a motorcycle of different nationality wearing groovy clothes, and with fake teeth stuffed in its mouth.

Yeah, Meyers may not be real-deal British, but you end up laughing your ass off anyway. What, pray tell, is wrong with that? —Mark Hoyer, Sports Editor

WHAT’S THIS FASCINATION WITH NEOnostalgia? I understand the attraction to old bikes, cars, guitars, even music, but it only makes sense when the item is authentic. And this W650, nice as it is, isn’t any more of a Triumph Bonneville than a Drifter is an Indian Chief. It’s a Mazda Elan, an Ibanez Les Paul, Pat Boone’s heavy-metal album.

I could forgive Kawasaki’s transgression if the W650 was based on its old W1 or W2, but those were BSA clones, whereas this one’s all Triumph. Last I checked, Triumph was still in business, and working on a new Bonnie of its own. Is there no shame?

Of course, the last time Kawasaki tried tapping into its own history, with the Z-l-cum-Zcphyr 1100, it bombed bigger than Hiroshima. But there is hope: The ZRX1100 has done quite well in its Eddie Lawson Replica livery. Maybe the Zephyr was just ahead of the curve?

Oh well, I’ll give Kawasaki credit for one thing: At least it isn’t copying Harley-Davidson like everyone else.

—Brian Catterson, Executive Editor

AS THE RESIDENT BRITBIKE BLOKE, WITH a Triumph, a BSA and a Norton all happily drooling on my garage floor, here’s my take on The Great Limey Lookalike Controversy.

Get over it!

Truth to tell, Em more offended by the clowns who ran England's motorcycle industry into the ground in the 1970s. If Triumph had summoned the gumption to build something as good as the W650 motor back then, the company never would have gone into its long, protracted death rattle.

That the W650—originally intended for Japan only—is coming to America can be traced to a grass-roots letter-writing campaign (many from Cycle World readers) imploring its importation. After all, if you don’t want a sportbike and you don’t want a V-Twin cruiser, there aren’t a helluva lot of options, especially if a sub-500-pound diy weight is your goal.

Just 1000 W650s will be brought in. Something like 400,000 streetbikes will be sold in the U.S. this year. The market can stand a thousand Akashi-built Bonnevilles. In fact, it’ll be the better for it.

—David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief