NEVER TOO YOUNG

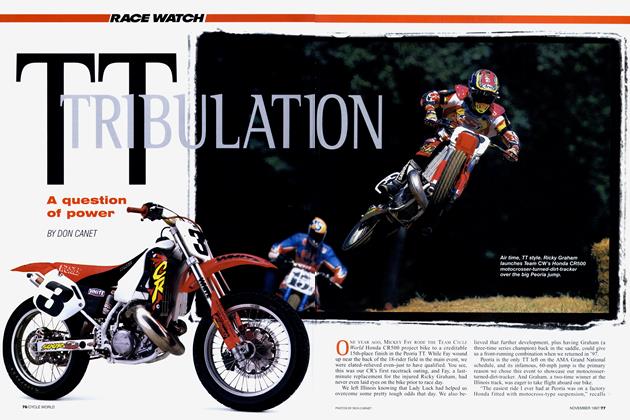

RACE WATCH

At age 26, Rick Johnson, the winningest supercross rider in history, has retired. But he's not done racing.

BRIAN CATTERSON

IT CAN'T BE. HOW CAN THIS MAN, 26-years-young and and an absolute vision of health, be retired? He looks as fit as ever-maybe even fitter. There are no signs of the injuries that have plagued him over the past three seasons. Rookie of the ear in 1981; seven-time AMA motocross champion; three-time member of the winning U.S. MX des Nations team; factory rider for Honda and Yamaha-all history now. the tact remains that Rick Johnson, known the world over as “RJ." the most dominant motocross racer of the late 1980s. has hung up his shoulder pads for good.

As Johnson explains, it didn't happen overnight. His brilliant career was sidetracked by a series of crashes and injuries which began w ith a freak collision during practice for the opening round of the 1989 250cc outdoor championships at Gatorback Cycle Park in Gainesville. Florida.

“1 passed Denny Storbeck in a turn, and when we went up the following hill he got crossed up and landed on me," Johnson recalls. “He says I crossed in front of him. but,> regardless, the result was his front wheel landed on my elbow', which shoved my hand underneath the handlebar and folded my hand back to my arm.”

Johnson underwent three hours of surgery that afternoon to repair his dislocated and broken wrist, followed by three months of therapy and rehabilitation at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Colorado. There, he says, he got into the best cardiovascular shape of his life in preparation fora return to racing. But his anxiousness to make a comeback would, in the long run, prove to be his undoing.

“I started back riding too hard: I wasn't gradual enough with it,” he says. “When I came back and won the 1989 USGP at Unadilla, I was really strong, but from that point, my hand got w'orse. After that, I rode over my head in Minnesota—I fell and separated some ribs from my sternum. I was too desperate. I went in with the attitude that if I messed up that whole year. I'd never be able to come back.”

Mess up the year he did. but he rebounded quickly, getting l 990 off to a good start with a win in the Paris Supercross. And although he didn't do as well in Japan, nor in the opening rounds of the Camel Supercross Series, his return to Gainesville was > triumphant as he outdueled his Honda teammate, Jeff Stanton, to win the first 250cc outdoor national. Things were looking up for Johnson. But his good fortune was short-lived, because one week later, at the Daytona Supercross, fate struck again.

“I made a mistake," he recalls matter-of-factly. “When 1 landed off a jump, my bike bogged and it threw me over the handlebars. 1 think I hung on too long, because the handlebar pinched my hand against the ground and broke it.”

So. Johnson was hurt again. And. despite the fact that he should have, by now', known better, he again forced a return to racing.

“It didn't hurt as much as when 1 dislocated my wrist, so I didn't think it was that bad," he says. “I didn't want to sit out another year, so I came back too soon.

“I didn't do very well in the Pontiac ( Michigan) Supercross, and then, w hen 1 went down to do some testing prior to the Tampa (Florida) Supercross, my hand was hurting really bad. 1 went and had some X-rays, and had a specialist look at it. 1 le said that it was still broken. 1 had to have the bone cut clean, and have a bone graft from my hip put in my hand, and then more pins for another couple of months.”

Doctors had some sobering news for Johnson. “That was too bad blows to my hand. One more, and they would have to fuse it,” he says.

Johnson was at a crossroads.

“1 thought about retiring." he admits. “I was getting married; I had an opportunity to race cars; a lot of things were happening. But I thought that if 1 walked away from motocross on two bad notes, that I would always go to races and think that I could come back—that if I hadn't quit. 1 could still do it. So, 1 decided to go out and give it my all this year.”

Johnson trained hard with Broc Glover during the off-season, but not long into the 1991 season, another problem surfaced. He blamed a crash at the San Diego Supercross on a stuck throttle, but when a similar incident occurred at a practice track soon after, he realized it was him. not the bike.

“1 was having trouble with my hand sticking,” he explains. ”11 seems like my hand would hit a certain spot and then let go, and when> I'd regrip I'd have a handful of throttle. When I hit the whoops at San Diego, it threw me off. I was lucky I wasn’t hurt there.”

Johnson sat out the next few races, consulting sports physician Dean Miller and other specialists to see if there was a fix for his troublesome wrist. The verdict was no, there was nothing that could be done, and surgery was deemed too risky.

“That’s when I talked with (Honda team manager) Dave Arnold and told him I had given it my all, but that I had nothing left to give,” Johnson says. “I had the desire, but a physical problem was holding me back. My body just wouldn't allow me to get on top of the bumps and go wide-open, because if I dropped a wheel, I was going over the bars. I didn't have the strength to hang on.”

But Johnson wasn't only thinking of himself.

“I didn't want to go out and race around and chance hurting somebody else or myself again,” he says. “I'd hate to land off a jump and bean Damon Bradshaw or someone and end both our careers over my greed, or my stupidity, because I didn't listen to the signs.” It was a difficult decision, but Johnson opted to retire.

Honda saw eye-to-eye with Johnson, and though he was released from his competition contract in order to pursue automotive racing, the company retained him for public relations work and testing.

“They’ve been a really good company,’’ Johnson says of Honda. “I think they understand that I didn't go into this last year of competition just to get some money out of it. The intention I had was to win all three championships.”

That goal—winning the supercross, 250 and 500cc outdoor national championships in one year—was one which Johnson never met.

“There was always something that kept me from winning all three,” he says. In 1986, his first year with Heñida after leaving Yamaha, Johnson lost the 5ÜÜCC title to his teammate, David Bailey. In 1987, accidents and injuries allowed Jeff Ward to beat him in the supercross series. In 1988, he lost the 25()cc outdoor title to Ward when his bike seized. It was frustrating, he says, but it’s all behind him now.

These days, Johnson has other things on his mind: He wants to make the jump to car racing. He’s attended the Bob Bondurant and Skip Barber roadracing schools and. most recently. the Buck Baker NASCAR school. He has two race-karts which he drives often. And he just purchased a showroom-stock 1989 Chevrolet Camaro in which, two days after this interview, he hoped to qualify for his SCC A license.

He has an action plan for his new career, starting with off-road racing of another sort. “I’ve talked to some

people and there's a good chance I'll be in a stadium truck next year,” he says. “Then, I'd like to make the transition to pavement racing.”

His ultimate auto-racing goals? “If it's open-wheel. I want to win Indianapolis. If it's NASCAR, I want to win Daytona.”

Though he says this jokingly, there's a hint of confidence in the words, as though it will only be a matter of time before he is competitive on four wheels.

Besides making a career change, Johnson is a newlywed, and he and his wife Stephanie have a few projects of their own. “We’re trying to finish the house, and we just found out that we have a baby on the way, so there's a lot going on in my life,” he says.

How would Johnson like to be remembered, now that he's leaving the sport of motorcycle racing behind?

“Rex Staten once said to me, ‘Last week a hero, this week a zero.’ And that stuck in my mind. As soon as you walk away, as soon as you're injured, you're forgotten. I'd like to be remembered for being aggressive, for being relentless.”

That's exactly how David Bailey, multi-time champ and Johnson's former Honda teammate, remembers him. “Nobody ever put so much fear in me during a race,” he says. “Ricky made me more nervous than anyone. Once he was on your tail, you couldn't shake him. He was able to dig deeper than anyone.”

Roger DeCoster, five-time world champion and Team Honda adviser, agrees with Bailey. “When Johnson was at his best, he was the same as Bob Hannah; Some guys can only close a second a lap. but Johnson and Hannah could make a big effort and close the gap in just a couple of laps,” says DeCoster.

And Hannah? What does the livetime national champ say about RJ?

“Johnson was tough and he wanted it. Johnson, Stanton, Bayle: They're all a different breed. Ninety percent of the new kids don't know what ‘want’ is. Johnson wasn't a natural talent, though; he worked hard. I've got respect for a guy like that.”

Respect is a word you here many times when people talk of Rick Johnson—rightfully so. Whatever happens in the future, as Johnson himself puts it, “I know that, at one time,

I was the best.”

There's little danger that anyone will ever forget that. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1991 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1991 -

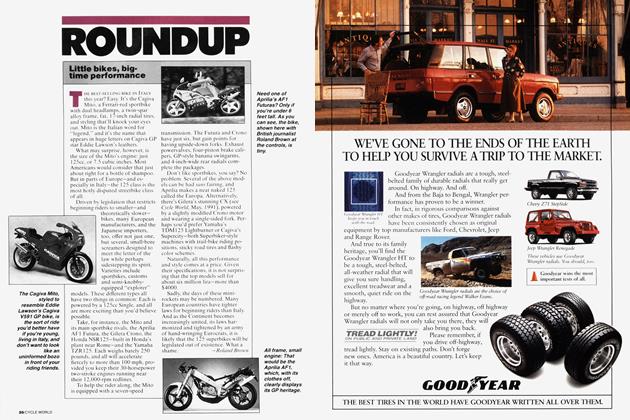

Roundup

RoundupLittle Bikes, Big-Time Performance

October 1991 By Roland Brown -

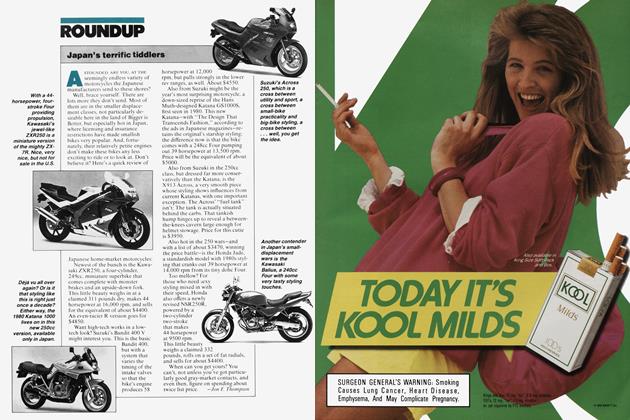

Roundup

RoundupJapan's Terrific Tiddlers

October 1991 By Jon F. Thompson