Clipboard

RACE WATCH

Lightning strikes Scott Russell twice

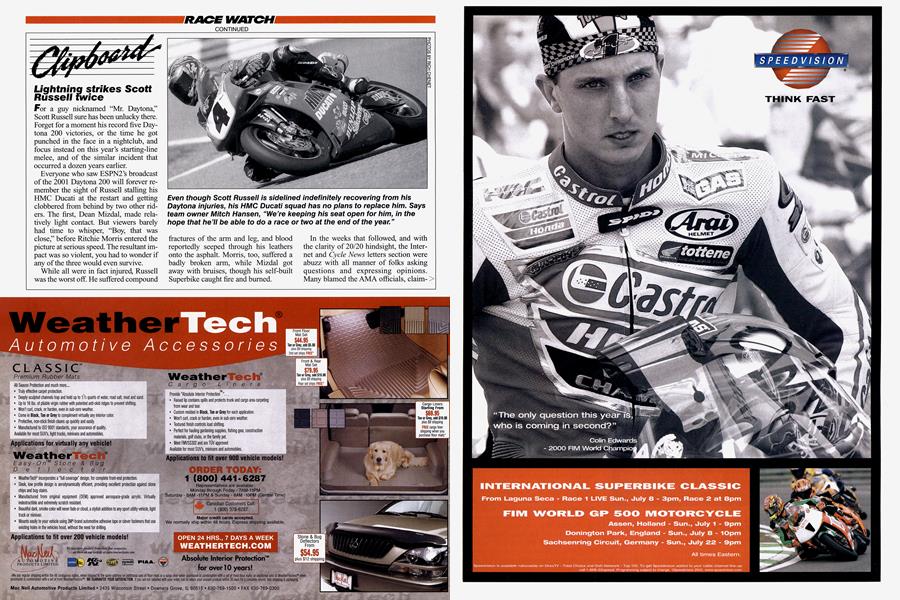

For a guy nicknamed “Mr. Daytona,” Scott Russell sure has been unlucky there. Forget for a moment his record five Daytona 200 victories, or the time he got punched in the face in a nightclub, and focus instead on this year’s starting-line melee, and of the similar incident that occurred a dozen years earlier.

Everyone who saw ESPN2’s broadcast of the 2001 Daytona 200 will forever remember the sight of Russell stalling his E1MC Ducati at the restart and getting clobbered from behind by two other riders. The first, Dean Mizdal, made relatively light contact. But viewers barely had time to whisper, “Boy, that was close,” before Ritchie Morris entered the picture at serious speed. The resultant impact was so violent, you had to wonder if any of the three would even survive.

While all were in fact injured, Russell was the worst off. He suffered compound

fractures of the arm and leg, and blood reportedly seeped through his leathers onto the asphalt. Morris, too, suffered a badly broken arm, while Mizdal got away with bruises, though his self-built Superbike caught fire and burned.

In the weeks that followed, and with the clarity of 20/20 hindsight, the Internet and Cycle News letters section were abuzz with all manner of folks asking questions and expressing opinions. Many blamed the AMA officials, claim> ing that if they had simply called for a waving-yellow flag at the site of Mike Ciccotto’s relatively minor fall in the infield, odds are nothing more serious would have happened. Instead, they brought out the pace car, which led to a harrowing incident on the banking, a red flag, a restart, and the very starting-line melee in which Russell was injured. But to be fair, they’d have needed a crystal ball to predict that chain of events.

One of the more controversial criticisms was aimed at Russell himself,

suggesting that if he had just stayed put and raised his arm instead of attempting to paddle to the edge of the track, the riders behind him would have been able to take evasive action. Yeah, well, sorry, but that didn’t work the first time Russell stalled at the start of the Daytona 200, so who’s to blame him for trying something different this time?

Flash back to 1989, Russell’s first year as a factory Superbike rider. When the green flag flew to start the 200, Russell stalled his Yoshimura Suzuki and was rammed from behind by privateer Mark Bougas, whose bike was so severely damaged he tried to get Yosh to pay for repairs. Russell was fortunate to escape uninjured that time, and in fact made the restart, though a damaged chain tensioner sustained in the accident ultimately dropped him from contention.

This time, he wasn’t as lucky. Following the accident, the 36-year-old spent a week in the Daytona hospital, and then another two in one closer to his home in Atlanta. Numerous surgeries and blood transfusions later, he finally was released to begin the long recovery at home. I caught up with him there as this issue was going to press on Thursday, April, 18th. The obvious question was, how was he doing?

“I’m hurting every day,” Russell drawled through the painkillers. “This is the worst pain I’ve ever been through. I wouldn’t wish this on my worst enemy.

“The femur’s not healed yet, but the doctor is happy with its progress. The thing is, there’s a huge hole in my leg that a nurse comes over to pack with gauze twice a day. There’s bone missing from my arm, so they’re going to have to do a bone graft to get the two parts to grow back together. I’m going back to have skin grafts on the leg soon. The plastic surgeon is the same one who did my eyelid after that ‘other’ Daytona deal. After that, I can get in the gym and start working out. I can walk with a cane right now, but I don’t go anywhere.”

As for his long-term prognosis, Russell is guarded but optimistic. “I don’t think about how long it’s going to take to get better. Time right now doesn’t matter to me. It’s painful, but it’s a good time to let my life slow down and figure some things out. It’s bad, but in a way, it’s been good.

“As for racing, I don’t know. I’m gonna miss this whole year, you can bank on that. I know Miguel (Duhamel) came back after being out that long with a broken leg, but that’s reaching. I mean, you miss a whole year...”

Should it turn out that this year’s Daytona 200 was Russell’s last race, he’ll be okay with that. “If I never race again, that’s all right. It’s been a good career. I don’t have anything left to provethough that’s what I was trying to do this year! The last few ‘down’ years (with the Harley-Davidson team) were just tearing me apart. I just wanted to do something, anything else. I know I can > still win. But I'm tired of being Scott Russell the racer. Now, I just wanna be Scott Russell the person."

As for his nickname, ".Mr. Daytona" is okay with that, too. "It's a good name, I like it," he said. "So many off-the-wall things have happened to me there, good and bad. But maybe Mat Miadin can have it someday." -Brian Catterson

Vance makes NHRA top 50 list

When the comprehensive history of mo torcycle dragracing is written, Terry Vance will be ground zero. If not for Vance, and his long-time engine-builder and partner Byron Hines, motorcycle dragracing might never have gained the popularity that it currently enjoys, and there most certainly would not be a Pro Stock Bike class at NIIRA events. Throughout his career, few individuals in all of motorsports were as well-known, as well-liked or as influential as Vance, who retired in 1988 as one of the NHIRA's all-time winningest racers.

In recognition of his accomplish ments, Vance was recently added to the NHRA's list of the top 50 drag racers of all time. The list, which coincides with the NHRA's year-long 50th Anniver sary celebration, was compiled from votes cast by more than 40 industry in siders including journalists, officials, historians and other experts. The list is being revealed one driver at a time, un til the end of the season, when the top driver will be named. In addition to ontrack success, the panel also took into consideration contributions to the growth of dragracing, technological achievements, fan popularity, and breakthroughs in marketing and spon sorships. Vance scored on all fronts and made the list in the 35th position, ahead> of a number of former Top Fuel and Funny Car world champions.

“It’s a great honor to be included on the top 50 list,” said Vance, who was genuinely surprised by his selection. “It doesn’t matter to me whether I’m 35th or 50th. As long as I’m on the list, it’s an honor. It’s pretty amazing to think that I could make this kind of a list, especially when you consider where we started and how the bikes were treated by the NHRA in the early days.”

Indeed. When Vance and Hines began touring the country in the mid-1970s, the thought that any substantial motorcycle presence at NHRA national events could be established simply didn’t seem likely. Vance, for instance, won one of the NHRA’s first official motorcycle races in Englishtown, N.J., in 1978, but received no prize money and even less recognition.

“They didn’t even have a trophy to give us,” he recalls. “We had to borrow Don Garlits’ Top Fuel trophy for the winner’s circle pictures. Another time, we sat outside the front gate for two days because they said they had nowhere to park us. It was bad; we had some people within the NHRA who supported us and saw the benefits of what we were doing, but it took a long time for them to really recognize us.”

More determined than bitter, Vance continued to stay the course. When the Pro Stock Bike class was introduced, Vance quickly dominated with his llOOcc Suzuki, compiling an unmatched 101-21 career record in elimination rounds en route to 26 national event victories.

When supercharged, nitromethanebuming Top Fuel Motorcycles began to gain popularity, Vance and Hines built one and ran the sport’s first 6-second > elapsed time with an historic 6.98 run at the now-defunct Orange County International Raceway in Southern California in 1984.

“The only time I ever saw fear in Terry’s eyes was when we fired up that Top Fuel bike,” Hines recalled. “I just know it scared the daylights out of him, but he never let on and he did a great job riding it.”

“I remember riding it, but as I get older, I wonder why I did,” Vance added. “When you’re doing it, it’s hard to explain-the emotional feeling, the adrenaline rush, the level of competition. I miss the feeling, but I don’t miss the fear that it gave me. It’s nice to have as a memory, though.”

Vance won the last race he competed in, the 1988 Winston Finals in Pomona, California, but not before he became the first rider to break the 7-second barrier on a Pro Stock Bike, a feat he accomplished a year earlier in Dallas, Texas.

Vance’s success on the racetrack was duplicated in the business world when he and his partner formed Vance & Hines, Inc. in 1980. That company has steadily grown into one of the industry’s largest suppliers of custom exhaust systems, ignitions and other specialty parts.

Throughout the 1990s, Vance fiieled his competitive desire with a successful AMA Superbike team. Vance & Hines rider Thomas Stevens claimed the AMA Superbike title in 1991 and two years later, Eddie Lawson won the Daytona 200 on a Vance & Hines Yamaha. Jamie James, Ben Bostrom and Anthony Gobert also won on V&H bikes.

Today, the Vance & Hines team continues to be very active in NHRA dragracing. Byron’s son, Matt Hines, is a three-time series champion aboard a 190-mph Vance & Hines Suzuki GSXR and the team is currently developing a Pro Stock Harley-Davidson, which is scheduled to debut later this year.

“Byron and I knew from the very beginning that we wanted to be racers, and we wanted to gain respect by winning,” said Vance. “But we also had a bigger plan: to have our business be in a very dominant position in the motorcycle market. Fortunately, we have achieved that. I don’t miss the politics of racing, but I do miss the sheer fun of riding a motorcycle to the envelope of performance.”

Two other motorcycle racers have thus far made the NHRA’s top 50 list. The late Elmer Trett, a Top Fuel Bike pioneer, was ranked 50th , while six> time Pro Stock Bike champ Dave Schultz, who recently died from colon cancer, was ranked 44th.

-Kevin McKenna

Honda gets it right

By the time we see new engines-racing or otherwise-they’ve been through the standard development process and are working well. It was a surprise, then, when Honda blew-up a bunch of engines at Daytona and early World Superbike rounds. Shrapnel from exploding engines is normally buried in dyno walls and ceilings, safely away from public view. After all, development engines do blow-that’s normal. Even in this day of predictive computer modeling, there is no way to be exactly sure about every heat-treat, every fillet radius, every material specification.

This past winter, I read a 1942 development log of a never-produced prototype aircraft engine. It went something like this: “Start up. Engine shutdown at 12 minutes, cracked layshaft bush. Reset new bush. Start up. Engine shutdown at 34 minutes, two broken cylinder studs, water leakage, rod bearing picking out.” On and on, never mentioning that at each step, oil and water had to be drained, everything minutely cleaned, checked, reassembled and adjusted back to starting conditions. Another engine type broke more than 100 experimental crankshafts before a successful design was achieved. Think of 100 catastrophic engine wrecks as the price of ultimate success.

We never see this fascinating world where the airliner-like reliability of modern engines is hammered out from the raw prototype. Not only must mechanics and technicians perform the> actual work, but failure-mode specialists must go over the broken pieces to discover what destroyed them. Sometimes, the wreckage is so bad that no cause can be found. Even so, the cause of failure must be designed out and drawings altered, parts must be pushed through the prototype shops at top speed, then assembled into new test engines. This is not inexpensive. Scores of test engines may be involved, none of these people is working for $5 an hour, and all departments are competing for scarce dyno and prototype shop time. Quick results require three shifts of all these highly skilled personnel, and you fight for your project’s priority over “unimportant” stuff like next year’s new models.

This is just for reliability. You also need to hit power and powerband goals. They seldom come to maturity in early testing, but must be coaxed from the design by many amendments, some of which can be quite extensive.

There was a rumor that Superbike work in Honda’s dyno facility was delayed for some days before Daytona by an explosion and fire during a test of the company’s new V-Five Grand Prix engine. This kind of thing is normal because four-strokes make power from rpm, and rpm equals stress. The engineer on this engine, Tomoo Shiozaki, has the reputation of using the Colin Chapman, of Lotus car fame, method, which is to design light and reinforce only what breaks. When this works, you end up with a reliable engine that is very light. Some of Shiozaki’s colleagues were amused by the resulting dyno fireworks, but Shiozaki has impressive achievements behind him, including the close-firing-order engine concept.

Italian engineers have long observed a principle that underlines Shiozaki’s thinking: It’s more successful to enlarge a small engine than to shrink a larger one. That is, it’s better to start light than heavy. For proof, look at Ducati, whose current Superbike engine has 500cc and 750cc roots. Ducati has had plenty of public blow-ups. In 1997, bore increases left the engines with ultra-thin liners that couldn’t be made thicker without moving the cylinder studs, requiring re-homologation. Liners broke. Before that, it was main bearing forces, breaking crankcases designed originally to be pounded by much smaller pistons. Blow-ups or not, Ducatis have been very successful.

Underweight ancestry is only one class of problem. Yamaha’s early FZR750based Superbikes spun bearings because a too-shallow (for racing) oil sump caused starvation. Today’s very deep sumps are the result. Suzuki broke early GSX-R race-kit rod bolts despite finiteelement design. The bolts broke in bending from big-end ovalizing under stress. Sometimes, you see only the fix, and must imagine the failures that led to it-as with the little flywheels on some Honda RC30 race cams, or the wide crankpin fillets on Ducatis.

In Japanese companies, policy rotates people from department to department. Naturally, when someone leaves a project, he takes his notes and data. Jokes are made to the effect that information could in this way leave a program faster than it is generated. Call it “un-development.” Can you think of a possible nonJapanese example? The proper use of development and the information it generates isn’t trivial.

In 2002, we’ll see which four-stroke > GP engine type best gets its power to the ground through tires that fit the maximum-permitted 6.25-inch-wide rear rim. Aprilia will most likely bring a VTwin, and Ducati has observed that without having to share parts with a streetbike, its V-Twin could rev 15002000 rpm higher. Lots of tire experience exists for lOOOcc V-Twins. Choosing three or more cylinders gambles that tire technology will magically appear. Honda has chosen five cylinders, a compromise between power and minimum weight. Yamaha picked the well-studied inline-Four. The Sauber Triple may only be the first of a type, three cylinders borrowed from an already-proven Formula One V-10. A Six, anyone? A V-Eight? One can only imagine how many parts will be imbedded in dyno-room walls.

Kevin Cameron

Grand Prix motocross' new world order

This past spring, beneath bright blue skies, the FIM kicked off its 45th consecutive season of Grand Prix motocross. And the opening round, billed as the Telefonica Movistar Motocross Grand Prix of Spain and held at the Circuit of Catalunya in Bellpuig (about 60 miles west of Barcelona), was the beginning of a new chapter for international MX.

Under newly appointed Dorna OffRoad Managing Director Giuseppe Luongo’s sweeping reform, the 125, 250 and 500cc classes now run on the same > day. Moreover, the traditional two-moto format that had been utilized for four decades was tossed out in favor of a more television-friendly, single 35minute-plus-two-laps configuration.

Changes aside, the Spanish GP had its own drama. In the 500cc class, fourtime World Champion Stefan Everts was finally healthy and back on championship-caliber equipment. After a disastrous 2000 season that saw him compete in just one moto (at Grobbendonk, Belgium), Everts parted ways with long-time personal manager Dave Grant, was released from his contract with Husqvarna and signed to race a super-exotic Yamaha YZ500FM.

Pitched as a rivalry for the ages, Everts was slated to go head-to-head with bitter rival Joel Smets. Defending 500cc World Champion and working-class hero of Belgian MX, Smets was not about to let the flashy Everts take away his hardearned number-one plate. In the 250ee class, reigning champ Frederic Bolley and series runner-up Miekael Pichón were once again poised to duke it out.

The 125ee class got things started with KTM’s James Dobb racing to victory in front of 25,000 fans. Second overall in ’00 and a former AMA National winner (Unadilla in ’93), Dobb is determined to win his first world title. Placing second was teammate Thomas Traversini of Italy. Third was three-time 125c World Champion Alessio Chiodi, who is back in Europe after an injurybattered tour of America. In the 250ce class, Team Suzuki’s Pichón drew first blood in a thrilling victory over German Yamaha rider Pit Beirer and Bolley.

After capturing the 500cc-class pole> in Friday’s timed qualifying, Everts took advantage of Smets’ lap-four, whoopsection bail-off. Everts’ teammate Andrea Bartolini was second, and Smets charged through the pack to finish third.

“I think Smets was a bit frustrated after the race,” said Everts. “At the start of the race, he was quick and going away from me. In his mind, he was the fastest rider in Spain, but he didn’t get his chance to win. You have to stay on two wheels, eh?

I expect to put more pressure on him, and I think he’ll make more crashes.”

Round Two took place in the deep, cocoa-brown sand of Valkenswaard, Holland. Enjoying a home-field advantage, 125cc riders Erick Eggans and Marc de Reuver placed first and third. Pichón captured the middleweight division, outriding Irishman Gordon Crockard and teammate Josh Coppins of New Zealand. In the 500cc class, the burley Smets put on a dazzling show of speed and strength. Aboard his orange KTM Thumper, the four-time class champ rode to a 32-second victory over Everts and fellow Belgian Mamicq Bervoets.

With the series rapidly gaining popularity in Australia, more than 32,000 fans converged on the town of Broadford to watch the third round of the championship. The highlight of the day was a phenomenal performance put in by local Andrew McFarlane. After leading the early stages of the 500cc GP, McFarlane was passed by the electric-smooth Everts. The Australian Yamaha rider nonetheless held on to finish second overall. Another relative unknown, Swedish Husqvama rider Jonny Lindhe, wound up third.

In the 250cc class, Pichón continued his conquering ways with another smooth, methodical victory over Crockard and Yamaha rider Claudio Federici. Bolley, meanwhile, had an awful day Down Under, placing 11th. Dobb once again claimed the 125cc class with a win over Yamaha-mounted Italians Alessandro Belometti and Chiodi.

Heading into Round Four at Genk, Belgium, Everts holds an 18-point advantage over Smets. In the 250cc division, Pichón has a perfect score of 75 points with his closet pursuer, Crockard, 33 points adrift. Finally, in the eighthliter class, Dobb holds down the sharp end of the leader board with 70 points. Chiodi is second and Eggens third.

There’s lots of racing still to happen, but it would appear Luongo’s new system is working well, even with half the motos of the old formula. Go figure.

Eric Johnson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

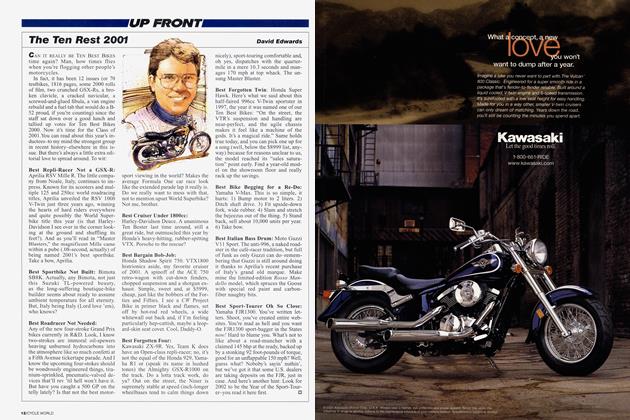

Up FrontThe Ten Rest 2001

July 2001 By David Edwards -

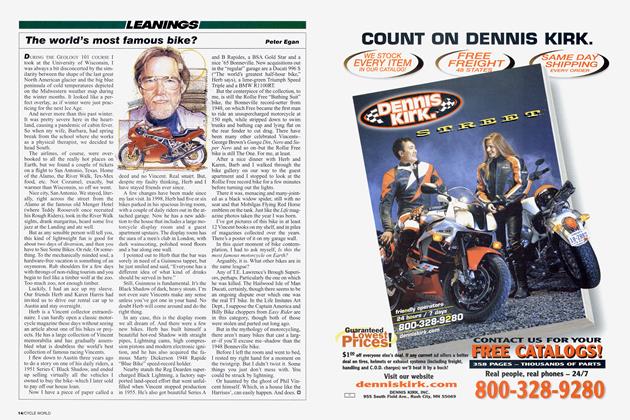

Leanings

LeaningsThe World's Most Famous Bike?

July 2001 By Peter Egan -

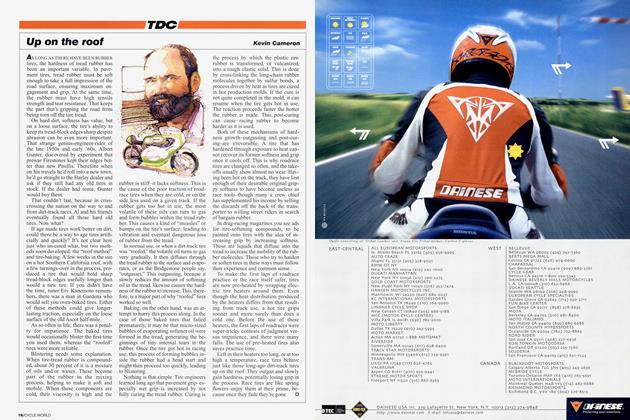

TDC

TDCUp On the Roof

July 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupExcelsior-Henderson Gone Forever?

July 2001 By Terry Fiedler, Tony Kennedy -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Retro Big-Bangers

July 2001 By Matthew Miles