THE TRANSATLANTIC MATCHES

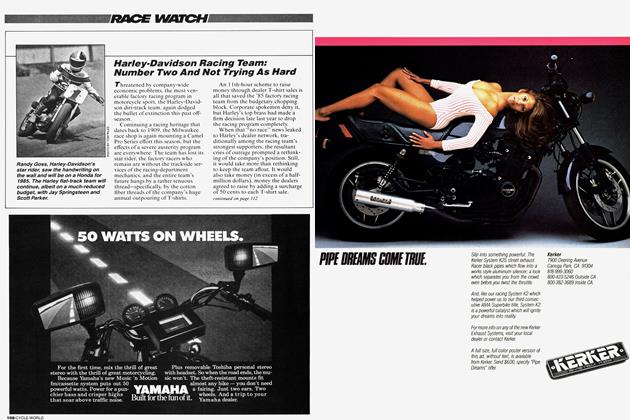

RACE WATCH

RON LAWSON

That’s no way to treat your host

DAVE DESPAIN

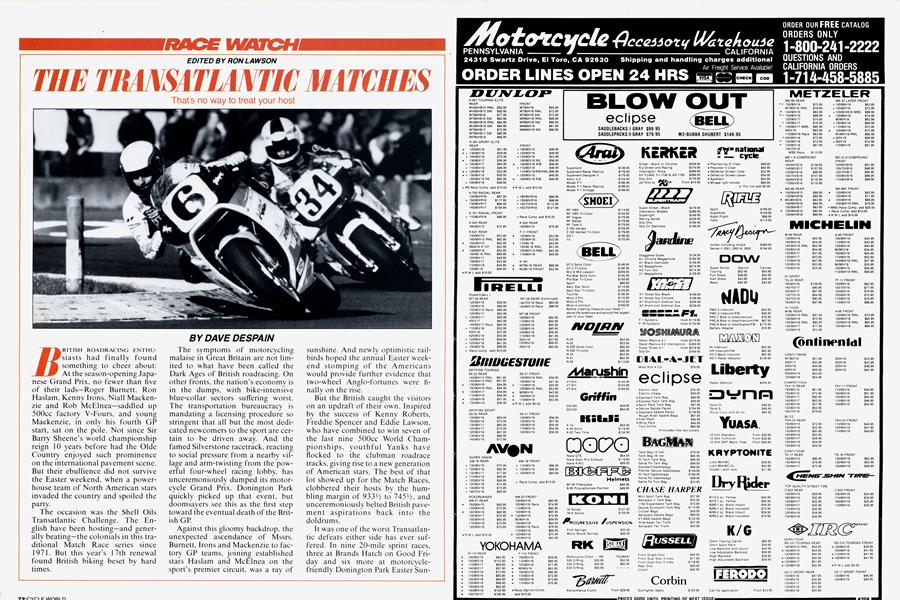

BRITISH ROADRACING ENTHUsiasts had finally found something to cheer about: At the season-opening Japanese Grand Prix, no fewer than five of their lads—Roger Burnett, Ron Haslam, Kenny Irons, Niall Mackenzie and Rob McElnea—saddled up 500cc factory V-Fours, and young Mackenzie, in only his fourth GP start, sat on the pole. Not since Sir Barry Sheene’s world championship reign 10 years before had the Olde Country enjoyed such prominence on the international pavement scene. But their ebullience did not survive the Easter weekend, when a powerhouse team of North American stars invaded the country and spoiled the party.

The occasion was the Shell Oils Transatlantic Challenge. The English have been hosting—and generally beating—the colonials in this traditional Match Race series since 1971. But this year’s 17th renewal found British biking beset by hard times.

The symptoms of motorcycling malaise in Great Britain are not limited to what have been called the Dark Ages of British roadracing. On other fronts, the nation’s economy is in the dumps, with bike-intensive blue-collar sectors suffering worst. The transportation bureaucracy is mandating a licensing procedure so stringent that all but the most dedicated newcomers to the sport are certain to be driven away. And the famed Silverstone racetrack, reacting to social pressure from a nearby village and arm-twisting from the powerful four-wheel racing lobby, has unceremoniously dumped its motorcycle Grand Prix. Donington Park quickly picked up that event, but doomsayers see this as the first step toward the eventual death of the British GP.

Against this gloomy backdrop, the unexpected ascendance of Mssrs. Burnett, Irons and Mackenzie to factory GP teams, joining established stars Haslam and McElnea on the sport’s premier circuit, was a ray of sunshine. And newly optimistic railbirds hoped the annual Easter weekend stomping of the Americans would provide further evidence that two-wheel Anglo-fortunes were finally on the rise.

But the British caught the visitors on an updraft of their own. Inspired by the success of Kenny Roberts, Freddie Spencer and Eddie Lawson, who have combined to win seven of the last nine 500cc World Championships, youthful Yanks have flocked to the clubman roadrace tracks, giving rise to a new generation of American stars. The best of that lot showed up for the Match Races, clobbered their hosts by the humbling margin of 933Vi to 745 and unceremoniously belted British pavement aspirations back into the doldrums.

It was one of the worst Transatlantic defeats either side has ever suffered. In nine 20-mile sprint races, three at Brands Hatch on Good Friday and six more at motorcyclefriendly Donington Park Easter Sunday and Monday, the best performance the British could muster was a single runner-up finish in raindrenched race number five. Otherwise, Californian Wayne Rainey and Texan Kevin Schwantz combined to win every race, and the top of the box score reflected the extent of the U.S. romp.

Schwantz, the U.S. captain, rode a factory Suzuki GSX-R750 to individual high-point honors by a narrow margin over Honda-backed Daytona 200 winner Rainey, who was consoled by his five race wins to Schwantz’s four. Gary Goodfellow, one of three Canadians on the American team and the only rider capable of keeping Schwantz and Rainey in sight, finished third in six of the nine races and third overall.

A distant fourth came the first member of the home team, Richard Scott, a New Zealander who migrates to the Isles during racing season. He scored a runner-up finish behind Schwantz during Sunday’s shower at Donington, but beyond that he was no better than fourth and no worse than sixth in seven of the remaining eight races. He did not start the finale; his team’s cause, by then, was badly lost, and he needed to catch a plane to the Spanish GR

As for the reasons behind this year’s flogging, the British weren’t at all reticent. “Our tackle just isn't as good as yours,” said series veteran Keith Heuwen, and he wasn’t fishing for an excuse; the British bikes were inferior to those of the Americans, and for good reason.

See, to entice the visitors into participating each year. Transatlantic rules have necessarily accommodated the Americans from the outset. Veteran observers recall the second running of the Match Races way back in 1972, when the normally polite British openly scorned Cal Rayborn’s dirt track-based HarleyDavidson XR. (That scorn gave way to chagrin when Calvin and his lowboy clipped a full second off the outright motorcycle lap record at Brands Hatch.) Later, when the Americans invented the Formula 750 class, the Transatlantic was quick to embrace Yamaha TZ750s, the only machines the visitors had. And now that hotrodded streetbikes are the Stateside racing rage, match-race rules—much to the disadvantage of the home team—dictate not only Superbikes but American-spec Superbikes at that.

So Rainey and Schwantz came equipped with their 170-mile-perhour Daytona factory rocketships, and the British commentator frequently reminded the home folks that Schwantz’s front fork alone cost a rumored $30,000. Even Goodfellow, whose modest budget dictates a virtually stock GSX-R, sported a borrowed exhaust, the Yoshimura titanium system that weighs seven pounds and retails for $ 1700. In contrast, the home-team “tackle” was drawn from the British division known as “Superstock.” Class rules allow any modification so long as it is made to a standard part, and that is a severe limitation indeed.

Asked his view of the alleged equipment discrepancy, North American team member Reuben McMurter argued, “They can buy the same kits we can,” which is certainly true. But a British rider’s guaranteed Transatlantic prize money, a little more than $1500, won’t cover the cost of a dry clutch, never mind all the rest of the kit pieces. After the Americans leave, the “stock parts” rule again prevails and the British rider has no use for all that technotackle. So the most economical bet is to race the Transatlantic on an outgunned Superstock and use that show-up money to buy gas.

With luck, this mismatch will disappear next year when Americanstyle Superbike racing gains worldchampionship status. British youngsters interested in racing tricked-up streetbikes will have additional opportunities to do so, and it’s likely the home team’s equipment next Easter weekend will more nearly equal that of the visitors.

Meantime, the man who built Richard Scott’s Superstock, the one best able to compete with the Superbikes, was Ron Grant, a New Zealander now living in London who once campaigned the U.S. Nationals. Grant fondly recalls racing for the American Match Race team in 1972 and ’73 on a water-cooled Suzuki Triple he lovingly nicknamed “the wicked wobbler.”

These days, Grant's home is Honda of Great Britain, which added its own verse to the country’s roadracing blues last off-season by shutting down its venerable racing department. The ensuing management shake-up ended with Grant running a one-man HGB race shop on a very modest budget and regularly testing interpretation of the Superstock rules.

For example. Grant reasons that if one melts down a standard piston and re-casts it to racing specs, one has merely modified the stock part. And while the tech inspectors aren’t that liberal, they do allow him to whack 180-degree Honda VFR crankshafts in half, then reweld them into a torquier, 360-degree configuration. Scott is not enthralled with that arrangement, but concedes that the bike “really puffs up off the corners.”

Grant prepared a similar VFR for the only big name adorning this year’s British team, but GP regular Ron Haslam’s mount was plagued by a variety of problems and he was no factor in the outcome. And beyond Haslam and Scott, the bulk of the British lineup might be generously described as hopefuls, for only three of them—Trevor Nation, Rhii Mellor and Heuwen—sneaked into the top 10 individual scorers.

In contrast, the rank-and-file of the American team consisted of proven pavement talent. Texan Doug Polen, who won nearly $100,000 in Suzuki and Hondasponsored club races last year and ran third (top privateer) in this year’s Daytona 200, made his international debut with a fifth-place individual ranking. He was just a hair’s breadth ahead of courageous Michel Mercier, the Canadian who broke his arm at Daytona, fell on it twice more at the Match Races and still scored in eight of the nine events.

Ohio’s Dan Chivington sandwiched his 29th birthday between a couple of hard Transatlantic crashes and still managed a top-10 individual ranking. And though both were sidelined for a portion of the series with mechanical problems, Canadian McMurter and Texas privateer Ottis Lance both beat more Brits than beat them, and that’s the key to victory in team competition.

Two other team members, Californian Bubba Shobert and Floridian John Ashmead. saw their series cut short by injuries. Shobert, also making his first international start, bailed in morning warm-up prior to the first race, breaking a finger and bruising his elbow. With a Camel Pro dirt track looming just two weeks hence, the reigning Grand National Champion wisely caught the next plane home. Ashmead highsided hard in the rain at Donington, lacerating his left hand and breaking the thumb badly enough to require surgery.

In retrospect, the most remarkable thing about the Americans' overwhelming victory is that it was only their sixth in 1 7 tries. After so many years of losing, such a dramatic shift in racing fortunes—particularly in these troubled times for the English — tempts us to ascribe some deeper meaning to this Transatlantic outcome, to search for evidence of a major change in the sport’s relative health in our two countries. What we find instead are a lot of parallels.

It’s important to recognize that England’s problems are also our own. The motorcycle economies in both countries are hurting; the bureaucratic harassment that British bikers are feeling for the first time is very familiar in the States; and the social disregard that left motorcyclists with the short end of the Silverstone stick has been a problem for American riders for years.

On the other side of the ledger, grass-roots roadracing in both countries is thriving. English competitors regularly choose among a half-dozen race meetings in a single weekend, all within a few hundred miles. A racer in America’s wide-open spaces has to drive farther to enjoy the same variety, but this country still currently boasts more more club races paying more prize money and enjoying more entries than ever before.

In England, that busy clubman scene has given the likes of Burnett, Irons and Mackenzie the opportunity to end the British roadracing doldrums; on these shores, the club-racing boom is producing the heirs to Roberts, Spencer and Lawson. And there is a balance in all this that goes beyond the lopsided ’87 Transatlantic score, a balance that bodes well for the roadracing future on both sides of the Atlantic.

Trans-Americas Rally, Attempt II

If at first you don't succeed, try, try again. That’s the motto of the organizers of the Trans-Americas Rally, the 31-day, 9000-mile motorcycle event that was scheduled to get underway last August—but didn’t.

You might have read about the proposed Rally in the May 1986, Race Watch; if so, you’ve probably wondered what ever happened. Well, nothing, to be precise. For a number of reasons, the Rally— which was supposed to get underway August 1 in Mexico City and finish on August 31 in Tuktoyaktuk, in Canada’s Northwest Territories, inside of the Arctic Circle-had to be postponed in mid-June. The organizers claim they could have juryrigged some last-minute solutions to the obstacles, but they chose to postpone the Rally for a year and do the job right. So the race is on once again for this August 1. And if things have gone as planned, the event should be underway by the time many of you read this.

For those of you who don’t already know, this Rally will be contested by 99 riders on 33 three-rider amateur teams, with each team having come from a different country around the world. As was the case last year, CYCLE WORLD was given the responsibility for choosing and managing the U.S. team. And after much deliberation and consideration, we decided to go with seasoned veterans rather than young lions, choosing AÍ Baker of Hesperia, California, desert racer extraordinaire and multiple Baja 1000 winner; Bill Uhl of Boise,

Idaho, a top ISDT rider of the Seventies; and Tom Young, an experienced all-around off-road racer from Portland, Oregon. This trio will ride 1987 Honda XRóOORs that will be specially set-up by AÍ Baker, who not only is an accomplished racer, but—as the proprietor of XRs Only, an aftermarket company specializing in high-performance components for Honda XR models—is probably the country’s leading expert on the preparation of XRs for competition.

Obviously, such an ambitious event is a nightmare to organize, particularly the part that will pass through the United States; trying to talk city, state and federal government agencies into sanctioning a motorcycle competition is a herculean undertaking. But if the Rally actually comes off this time—and we’re quite optimistic that it will—its competitors will have participated in what surely will have been the most grueling test of man and twowheeled machine ever. And we’ll have the inside report on it in our December issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialSummer of '47

August 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1987 -

Departments

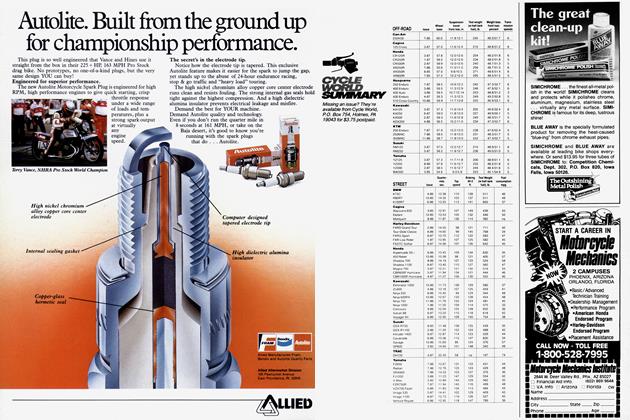

DepartmentsSummary

August 1987 -

Roundup

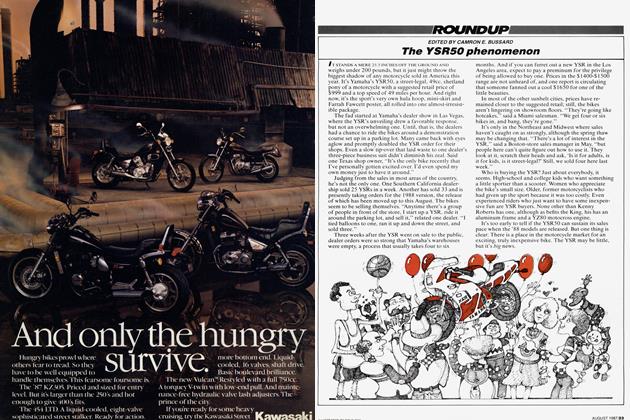

RoundupThe Ysr50 Phenomenon

August 1987 By Ron Griewe -

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the Performance of the 400s And Into the Price of the 750s

August 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupVelocettes Live Again

August 1987