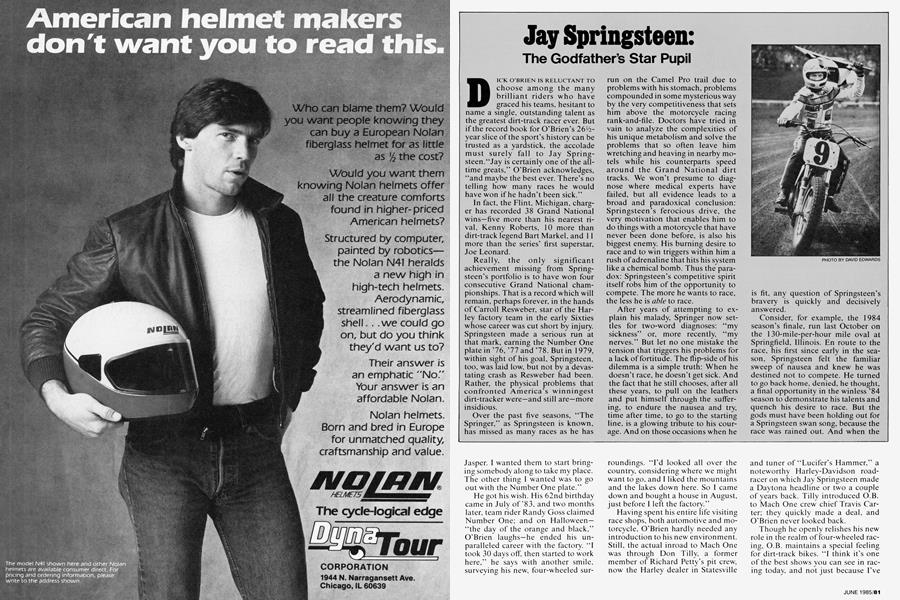

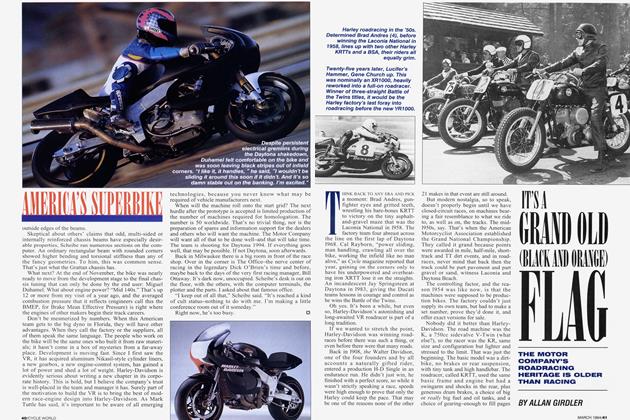

Jay Springsteen: The Godfather's Star Pupil

DICK O'BRIEN IS RELUCTANT TO choose among the many brilliant riders who have graced his teams, hesitant to name a single, outstanding talent as the greatest dirt-track racer ever. But if the record book for O’Brien's 26½year slice of the sport’s history can be trusted as a yardstick, the accolade must surely fall to Jay Springsteen.“Jay is certainly one of the alltime greats,” O’Brien acknowledges, “and maybe the best ever. There's no telling how many races he would have won if he hadn’t been sick.”

In fact, the Flint, Michigan, charger has recorded 38 Grand National wins—five more than his nearest rival, Kenny Roberts, 10 more than dirt-track legend Bart Markei, and 11 more than the series’ first superstar, Joe Leonard.

Really, the only significant achievement missing from Springsteen’s portfolio is to have won four consecutive Grand National championships. That is a record which will remain, perhaps forever, in the hands of Carroll Resweber, star of the Harley factory team in the early Sixties whose career was cut short by injury. Springsteen made a serious run at that mark, earning the Number One plate in '76, ’77 and ’78. But in 1979, within sight of his goal, Springsteen, too, was laid low, but not by a devastating crash as Resweber had been. Rather, the physical problems that confronted America’s winningest dirt-tracker were—and still are—more insidious.

Over the past five seasons, “The Springer,” as Springsteen is known, has missed as many races as he has run on the Camel Pro trail due to problems with his stomach, problems compounded in some mysterious way by the very competitiveness that sets him above the motorcycle racing rank-and-file. Doctors have tried in vain to analyze the complexities of his unique metabolism and solve the problems that so often leave him wretching and heaving in nearby motels while his counterparts speed around the Grand National dirt tracks. We won’t presume to diagnose where medical experts have failed, but all evidence leads to a broad and paradoxical conclusion; Springsteen's ferocious drive, the very motivation that enables him to do things with a motorcycle that have never been done before, is also his biggest enemy. His burning desire to race and to win triggers within him a rush of adrenaline that hits his system like a chemical bomb. Thus the paradox; Springsteen’s competitive spirit itself robs him of the opportunity to compete. The more he wants to race, the less he is able to race.

After years of attempting to explain his malady, Springer now settles for two-word diagnoses: “my sickness” or, more recently, “my nerves.” But let no one mistake the tension that triggers his problems for a lack of fortitude. The flip-side of his dilemma is a simple truth: When he doesn’t race, he doesn’t get sick. And the fact that he still chooses, after all these years, to pull on the leathers and put himself through the suffering, to endure the nausea and try, time after time, to go to the starting line, is a glowing tribute to his courage. And on those occasions when he is fit, any question of Springsteen’s bravery is quickly and decisively answered.

Consider, for example, the 1984 season’s finale, run last October on the 130-mile-per-hour mile oval at Springfield, Illinois. En route to the race, his first since early in the season, Springsteen felt the familiar sweep of nausea and knew he was destined not to compete. He turned to go back home, denied, he thought, a final opportunity in the winless ’84 season to demonstrate his talents and quench his desire to race. But the gods must have been holding out for a Springsteen swan song, because the race was rained out. And when the event finally was run two weeks later, Springsteen blessed that historic track with as fine a performance as it has seen in its 50-year history. Spotting the rival Hondas a good three lengths down the straightaways each lap, Springer held on like a bulldog through the 25-lap main event, making moves in the draft and in the corners that kept even the most jaded observers spellbound.

The brillance of that rare performance was not lost on the fans. The biggest cheer of the day was not for race winner Ted Boody; not for race and series runner-up Bubba Shobert, who that day completed one of the most impressive stretch runs in series history; not even for newly crowned champion Ricky Graham. No, the fans reserved their most vocal praise for The Springer, when he caught and passed all three of his more powerful rivals off of Turn Two and took a brief, mid-race lead.

The resultant roar of approval that exploded across that venerable dirt circuit was, however, a fleeting moment in the spotlight for Springsteen as the more-powerful Hondas immediately streaked past him on the backstretch. But the crowd had confirmed a simple truth: Jay Springsteen still is the measure of excellence in Grand National motorcycle racing.

For 1985, Jay will again carry the Harley factory team colors and the hopes of thousands of H-D loyalists. A realignment of the factory racing program has paired him with an outside sponsor, Indiana motorhome builder Ken Parker, and an independent contract tuner, Parker employee Paul Chmeil. Says Parker, “We’re definitely going to be a low-pressure environment for Jay. We’re going to the races to have fun.”

If that lack of pressure can really be effected, it will perhaps be the key to a Springsteen comeback. Then again, the pressure Springsteen feels is selfinflicted, the product of his incredible determination, and therefore more difficult to alleviate. In any event, the ’85 season will answer many questions about his future, questions he has considered repeatedly and at length. “I’d like to win 50 Nationals,” he says, “and put that record up there where it will stand for a while. And when I quit goin’ fast on two wheels, I’d like to give four wheels a try.”

Might the comparatively secure confines of a race-car roll-cage calm the nerves that trigger Springsteen’s maddening, debilitating stomach attacks? Might he someday become the first racer since Joe Leonard to win national championships on two wheels and four?

With his former team manager, Dick O’Brien, firmly entrenched in the ranks of Grand National stock car racing, those questions have potentially interesting answers. For now, though, Springsteen is focused on the ’85 Camel Pro campaign and the formidable task of keeping his aging Harley in contention with the bulletfast Hondas. And if there is any justice in the world of racing, Springer will attempt that feat unimpaired by his mysterious malady; he will take each green flag of the ’85 season healthy, happy and fully equipped to demonstrate the dirt-track greatness that is his alone.Dave Despain

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialCountering the Steering Myths

June 1985 By Pauldean -

At Large

At LargeInside the Accidental Fortress

June 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1985 -

Rounup

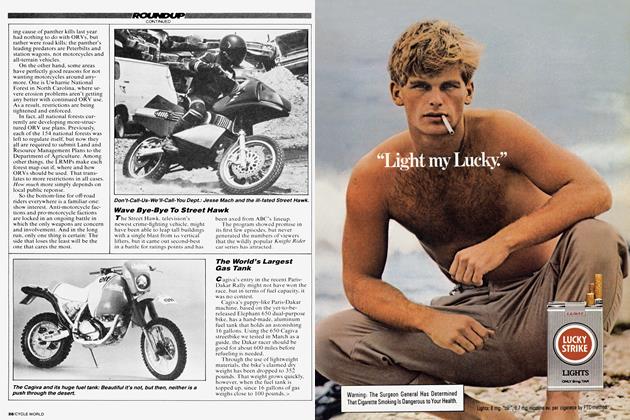

RounupLand Closure: the Fight For the Open Range

June 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupWave Bye-Bye To Street Hawk

June 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe World's Largest Gas Tank

June 1985