Riding the Steel Needle

Scenes from the last Cycle World GP Euro-Tour

JAMES B. PETERSEN

SOMETIMES YOU PICK UP THE PHONE AND YOUR LIFE changes. Last summer, David Edwards called to ask a favor. A family emergency had cropped up; could I take his place and cover the Cycle World GP Euro-Tour in Spain?

There was one problem. The tour happened at the same time as my daughter’s high school graduation. I took her aside and said it was her call: Did she want me to sit in a hot, sweaty gym trying to pick her out of a crowd of 750 cap-and-gowned classmates or would she let me ride through Spain and France for 10 days? Oh and by the way, was she aware of who would be signing checks for her benefit for the next four years?

I raised her well.

David told me what to expect. Over the past dozen or so years the magazine had invited readers to combine the pinnacle of roadracing, a European Grand Prix, with the pleasures of sporttouring, courtesy of Edelweiss Bike Travel. The rides had produced memorable moments and lasting friendships, but it was time for the program to end. This would be the last such tour. It would be, he said, unlike any ride I had ever taken.

He was, of course, absolutely right.

PREFLIGHT BARCELONA

I’m trying to walk off jet lag. Like everyone else on the Cycle World tour, I’ve learned to put some time between stepping off the plane and straddling a motorcycle. Barcelona rewards the effort. It is a city of glimpses, fleeting images down narrow streets, through courtyards, across café tables, things seen out of the corner of your eye. On the Ramblas, a tree-lined walkway that runs from the harbor through the heart of the old city, outdoor cafés offer tapas and drinks, while street performers and pedestrians provide visual delight. God and the Devil play chess.. .Dracula sleeps in a coffin.. .a puppeteer guides a green frog though complicated riffs on a tiny piano.. .Don Quixote, attired in recycled plastic bottles, tilts at tourists... a sketch artist stares at the snapshot on a cell phone and a face appears on paper.. .in the courtyard of a church a tiny woman sweeps up leaves as she has for hundreds of years.

At a pedestrian crossing, I notice that someone has altered the symbol for permission to cross. A bouquet of flowers has been etched into the green, so that when the tiny figure is illuminated, he appears to be hurrying toward a romantic liaison, flowers in hand.

MOTOMANIA CENTRAL

This is a city given over to two wheels. There are shops devoted to motorcycle helmets, which are as common as baseball caps (and treated with the same casual disregard, chained to scooters, tossed atop café tables or underneath). The billboards that don’t show sleek women in bikinis show MotoGP riders from Team Fortuna, fire blazing from exhausts, with odd cartoon-sized exclamations, “Canaaa!” or “A-Sacooo!” I have no idea what the words mean, but somehow, they need no translation. On the sides and backs of buses, Movistar riders beckon “Follow Me.” A window in one of the pricey shops along the Rambla is devoted to Valentino Rossi memorabilia, including a set of well-used Michelin rains. In America, the backboards on garages, the rough courts in parks and school yards, the gyms in schools, churches and YMCAs made Michael Jordan possible. In Spain we continually encounter motomania, from the tiny coin-operated sportbike outside a pharmacy to motorcycle pins and carved wooden bikes being sold in the stalls near the harbor to Rossi T-shirts and caps on kids in the street. (Oh wait, those are our guys just acting like kids.)

On the first day of the tour, part of our group will stop for lunch at a family restaurant situated at the bottom of a mountain pass. Two old men will enter the establishment, pull wooden chairs in front of the big-screen TV and watch silently the Mugello GR At a gas stop in the Pyrenees, we find a display case filled with tiny replicas of world-championship racebikes and will spend minutes pointing out Freddie Spencer’s ride, Agostini’s, Rossi’s. In Carcassone, the walled town used as a set for Kevin Costner’s Robin Hood, we will watch French kids pull wheelies and stoppies on their scooters, none of which seem to have mufflers.

This passion, this knowledge, will flow into the stands a week from now.

WHO ARE THESE GUYS?

Edwards had warned me that the people who come on the Cycle World GP tours are fanatics.

Over a continental breakfast I find out quickly how true that is. Terry Nauman, a geology professor who specializes in volcanic rock, owns five bikes. Randy Jones, an engineer who designs maintenance and safety protocols at the San Onofire nuclear plant, owns four. “Wild Bill” Beckman, an artist who spends a whole year on one canvas study, has four including some exotic racebikes. Mark White, a software engineer, owns nine, mostly Italian, and holds a special regard for his MV Brutale and the joy it brings soaring onto an entry ramp on his daily commute. They all own copies of the video Faster, use Tivo to tape European races, talk with affection of the time Rossi flipped Biaggi the bird at 150 mph, or the way Nicky Hayden can nonchalantly slide clear across the track on a certain turn, every time. They are connoisseurs, with the kind of passion that sheds non-riding friends. Terry admits that he comes on the MotoGP tours just to be around kindred spirits. “Hey, these guys make me feel normal,” he says.

They had met on an earlier Cycle World tour led by Paul Dean, and after a week of maniacal disregard for the laws of physics, an unrestrained stint of male bonding, and/or too many cappuccinos, had experienced an epiphany. They’d stopped at one of those roundabouts Europeans use to repel and confuse invaders, and posed beneath a roadsign that showed three routes to a town called Morón.

“Team Moron” was born. By the third day of this tour they will have worn their tires down to the cords, except for Marcus Lopez, who almost never lets the front wheel touch the ground.

On this trip they immediately recruit Frank Lenonicelli, an Italian cop from Boston, a weightlifter with two bikes, one of which he keeps in his living room. Frank has a Tony Montana/Scarface accent by way of Hahvad Yahd, especially evident when he says, “You guys are fahkin’ retahded.”

In addition to a passion for motorcycles, Frank is a devotee of laser hair removal. Now, there comes a moment when you realize that the waitress does indeed understand English. In Frank’s case, it was the remark, delivered full volume,

“No way I was gonna to let a complete stranger laser my scrotum...”

The combined knowledge is stunning. I listen to AÍ Olseen, a Baja dirtbike fanatic with 53 inches of scars on his torso and enough titanium screws in his body to light up every security gate in Europe, talk about converting a R1200GS motor to more-powerful ST-spec, running it on race fuel while he waits for his hacker friend to remap the Motronics. They compare sources for carbon-fiber panels to lighten the GS and fork seals for Bimotas, divulge tricks for getting 49-state models past California inspectors.

We are kids, age irrelevant. Tom Roach, who owns two Harley dealerships, talks about waiting at a train depot in Cody, Wyoming, for his first motorcycle to arrive, a mailorder Greeves. He recruited a group of friends from Vail to come on this tour-their idea of a warm-up lap was to spend a week touring southern Spain before joining our group.

Scott Mulavania, a.k.a. “Scoobie,” a Navy aviator who flies jets off carriers, sports a T-shirt from the Indian museum in Massachusetts that catches Wild Bill’s eye. “My first bike was a ’37 Chief,” he says.

“Did you buy that new?” I ask, and am admitted as a probie to Team Moron. I will guard the kill switch at stop signs, check that some prankster hasn’t flipped on the heated grips or added some treat to my continental breakfast. I haven’t had this much fun since junior high.

On Sunday we meet our guides and fill out the paperwork for our bikes. Roland, who for seven years has run the Harley tours for Edelweiss, says he is looking forward to the new challenge-“Harley tours, they are like...hiking.” Martin, a newcomer and ex-motocrosser, will share chase/ luggage-van duties and learn the ropes-on a Gixxer 1000! Jurgen, the chief guide, looks around the room and notes the number of women (five passengers, two riders). “Unusual for a Cycle World GP tour,” he says, laughing, “but, hey, men are better behaved around women.”

“They are?!” The voice, female and filled with skepticism, belongs to Beth Schott, a special agent with the Department of Interior, riding solo alongside husband Bill.

We walk to an underground garage and acquaint ourselves with our bikes. I watch riders pull out their own toolkits, adjust suspension, wire up GPS units and helmet intercoms, adjust seat and handlebar heights, check tire pressure, fill tankbags with cameras and maps. Tom Overbey, a lawyer from Arkansas and veteran of several CW tours, even brought his own aftermarket seat.

Joe and Ed Ramseur, who with family friend Olseen form “Tres Hombres,” go one step farther: They have brought along a vial of ashes, the cremains of their father, a longtime motorcycle fanatic. This is a ride, they say, he would have loved to make.

The couples mount with an easy grace that shows years of trust. Judy Sibley tells me that she used to indicate she was ready to ride by tapping her husband on the shoulder, the way soldiers tell the guy with the bazooka it’s loaded and ready to fire. Once, at a Vincent rally in England, though, he pulled away with her leg in midair. She subsequently changed the signal (to two hands around the throat?).

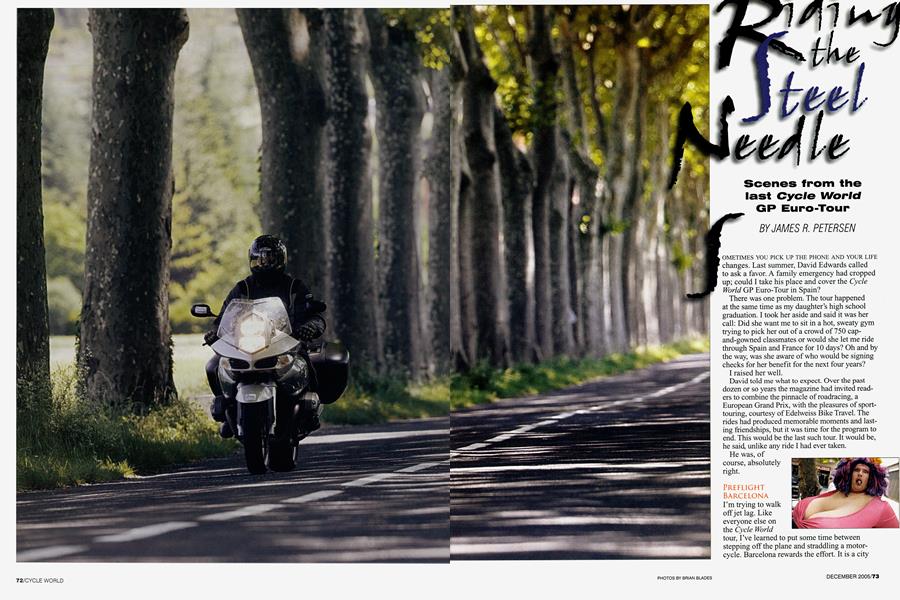

THE RIDE

Soon out of Barcelona, we move through hills of red-colored sedimentary rocks that used to be sea floor. Around the monastery at Montserrat the crags resemble salt-lick mountains, or beach castles after a million years of rain. The sandstone gives way to deeper rock, the upthrust of grey-hued limestone, and finally granite.

Not for the first time, I experience the conflict that is at the heart of sport-touring. Werner Wachter, impish founder of Edelweiss Bike Travel, once put it this way: “I never know whether to rise to the challenge of the road or to slow down and take in the view. In 30 years, this question has not been resolved.”

One road skirts a high overhanging limestone cliff where locals fill bottles with spring water made pure by its journey through stone. I turn off the motor, briefly, to listen to that sound.

There is almost no traffic. Entire roads pass beneath our wheels, our rhythm interrupted by a car or truck maybe four times in as many hours. We ride as a unit, reading the road, forming a peripheral consciousness of the mountain, a sense of the rhythm of the people who built this stretch of road. It is a heightened state of awareness, an act of sustained concentration. I call it Riding the Steel Needle. It is visceral. Just as looking ahead through a hairpin smoothes out the turn. The kind of anticipation, the knowing prediction, that

comes with the Steel Needle is breathtaking. We ride like gods.

At times, the Team Moron train numbers nine bikes, all traveling at elevated velocity-because there are no backmarker tourists, and

because they are incredibly fast. Chris Thibaut, who spends most of the first day taking a wheelie tutorial from Lopez, says in awe at dinner the first night, “I did things today that in the States would have sent me to jail for life.”

But Team Moron thinks that the Tres Hombres are crazy. They have watched the three riders pass with what seems like reckless abandon. “Wasn’t 90 mph fast enough for them?” someone wonders. They pass on blind corners, which causes Scott the jet pilot to confront them. One of the Ramseurs points to his helmet radio, explains that they are in constant communication, that the lead rider radios back the breaks in traffic.

“Oh man,” says Scott, “that’s cheating.”

I ride with Brian Blades, the Cycle World photographer. Where sport riders focus on the road, he focuses on everything but. He looks at a wall of rock and wonders how to use it in a photo; at a field of lavender or yellow and wonders what it will look like as a blur behind a passing bike. It is the exact opposite of focus, a kind of open peripheral vision. He asks me to ride in front, as an indicator that the road is going this way or that. This being Spain, I cannot help but think that we resemble Don Quixote and Sancho in search of windmills. Except that instead of a barber’s bowl, I have a carbon-fiber helmet and Brian, instead of a donkey, has 50 pounds of camera equipment on his back.

When I can’t find him in my mirrors, I know that he has spotted something. A cart led by a bickering old man talking to his uncooperative horse? A mother returning from market with her daughter, one hand protectively touching the child’s shoulder, the other gripped on a bag bulging with sustenance? The color of the shutters on a house just inches from the road? The flowers that hang from lampposts or bridges? A great hairpin where I can pretend to be an action model?

Distraction makes navigation impossible. I won’t say we get lost—I call it extended-play mode-but we are always the last to arrive at the hotel. I place the blame on the road signs in Spain and France, about what you’d expect in countries that have been repeatedly invaded. Street signs, if they exist, are on the sides of buildings, halfway down the block, about 10 feet in the air. Route numbers, if given, are an afterthought, printed on something the size of your wallet. I am the blind leading the blind.

Thankfully, we spend two days riding with Bill and Beth Shott and come to rely on their well-polished cross-country skills. Bill, also a federal agent, is so fast he can get to the next roundabout, read the signs, consult the maps and road book, dial up a secret spy satellite operated by the U.S. government, and by the time we are there have it figured out. When that fails, he simply talks to an old French guy, interprets body language into direction, and off we go. It doesn’t always work. We end up on a narrow lane that becomes a path to, of all things, an ostrich farm. “You think we ’re lost, imagine how they feel,” he says.

The riding couples (Bill & Beth and Roy & Shari Remus) have one pace; the two-up riders another-the men concentrate on the road, the women on the wonder. Jim & Cathy Wright, Jerry & Judy Silber, Naran & Janice Reitman, Tom & Sybil Roach, Marc Lashovitz & Brett Deutscher share stories about their day-the particular cathedrals, castles, the sleek black horses in one field, the women tending gardens or bicycling home from the market, the farmhands talking across a fence, the joy of meeting someone whose family has lived in the same house for 800 years. They keep journals, take photos and fill sketchbooks.

At the end of the second or third day, Judy will give a onesentence review of a day spent touring wine country: “That was better than a bottle of champagne and 40 roses.”

On the second morning of the ride, we approach a town built atop a rocky crag, lit by sun just clearing the mountains. I am so preoccupied with this reverie that I miss the turn. I think of Werner’s dilemma. On an Edelweiss tour of California I once listened to a wonderful woman, an animation artist for Disney, tear into a Cycle World editor. Why didn’t the magazine ever attend to the beauty made accessible by the sport? We were staying at a place in Mendocino that had an incredible herb garden, right next to where our bikes were parked. Couldn’t you show that, she wanted to know? The editor mused aloud, “I suppose we could shoot a rider doing a stoppie next to the garden. The caption might read, ‘Oh look, fennel.’”

You see the problem?

Team Moron and Tres Hombres have little time for art. Whenever Brian finds a stunning vista, he tries to recruit riders to make passes for the camera. One, two, maybe three passes and they are gone. Fame? A cover shot? Who needs it? Seeya.

At the end of the tour, when Brian shows the group images on a laptop, they will not recognize where on the tour the photos were taken. “I can’t see the pavement. Show me the pavement and I’ll tell you where we were.”

PYRENEES PACHINKO

The Edelweiss brochures proclaim that we would ride “uncountable turns, one after another.” I thought they were being lazy, so I try counting. I cannot get past seven before the road devours my attention. Someone suggests counting straightaways instead, or the number of times we get into fifth or sixth gear. I recruit the pillion ladies, ask them to count turns in 2-minute intervals, and if possible 10-minute intervals. Judy gets 71 turns in 10 minutes on a river road filled with sweepers. Cathy records 25 in 2 minutes, 60 in 10. That gives a range of between 360 and 750 turns/hour. Assuming a seven-hour riding day, that’s between 2520 and 5250 turns a day.

I admit to being a curmudgeon. How many bikes does Valentino Rossi own? How many miles a year does he ride? Compare our stats. On race day he will do what, maybe 300 turns in just under an hour? Big deal. What can you say about a sport where the better you are, the less you do it?

At the morning briefings the guides usually outline two routes-short and long, scenic or challenging. But improvisation {i.e. getting lost) is an accepted practice. We have maps, and between our starting point and next night’s hotel there is a latticework of roads. I have the sense of being in a pachinko machine; you know, with steel balls that ricochet through nails. At any moment there might be five or six splinter groups working their way down the red, yellow or white roads, poking their way along goat paths, riding the ridges or swooping along a river.

At times it feels like slapstick, one of those scenes in a Peter Sellers movie with speeding vehicles careening in opposite directions while old men look on. And there are old men in every town. I wonder if it is a paid position.

On Friday, we pass through the town at the base of Château de Peyrepertuse. Some opt to climb to the ruins of the Cathar-era castle, others settle for a postcard. Some order food from a sit-down restaurant, others grab sandwiches from a tiny shop. We venture down the Gorge de Galaumus, a narrow lane hacked into the cliffs above a raging torrent, one of the greatest engineering feats in road building, ever.

We scatter, and bikes go down. Leading Team Moron on a new K1200S, Roland hits a patch of gravel and when the bike hooks up, it is facing sideways. When a K1200S hooks up, that’s the direction it goes. Roland rides the bike down a ravine. It takes all of Team Moron to haul it back up, levering the behemoth one wheel at a time, 10 inches at a time. Hearing about this later I recall a film, El Cid, in which Frank Sinatra hauls a humongous cannon across Spain, accompanied by Sophia Loren in a peasant blouse. Randy Jones stripped off his leathers, but the effect wasn’t the same.

At dinner we learn that Jim and Cathy hit a corner packed deep with fresh gravel and went down hard. She broke a leg and is in the hospital.

Brian and I have our own gravel encounters of the French kind. We find mounds of the stuff on the roadside and realize that the seeding of corners with gravel is intentional. The French repair roads one ingredient at a time. Cars pass through the corner and distribute gravel down the median for hundreds of yards (Wild Bill tells us he just rode the ruts, a narrow line but one that didn’t require slowing down). At one point we negotiate a road where fresh oil had been drizzled-like the sauces on a desert or the splatter painting of Jackson Pollock-in no rational pattern. Coming around a corner we find a road crew, and watch. Some workers throw gravel in one direction while the guy with the oil hose merrily sprays in another. Impressionist road repair?

There’s nothing as harrowing as the sound of gravel hitting your face shield on a dark mountain road. But you go to sleep and wake with a lust for the road that can only be compared to skiers who line up for first tracks. Frank the cop explains, “It’s all about the next corner.”

Edelweiss has an almost musical sense, a way of orchestrating a day’s ride so that you end on something exhilarating. A river road, a mountain pass, a swoop down to a remote ski village. The last day of riding finds us arcing down the Costa Brava, on a road that follows the coastline. A pure romp. On our right, stunted green trees. On our left, sparkling blue water, the occasional isolated beach. And everywhere, sportbikes. My rearview mirror looks like a showroom floor, three or four models in each oval.

It seems like every bike in Europe is converging on Circuit de Catalunya.

NOTES OF A MOTOGP VIRGIN

Sunday morning, we follow 105,000 fans into the track, past tents selling official Rossi gear and T-shirts for Dani Pedrosa, the local 250 favorite. Overhead, helicopters fly VIPs into and out of the arena.

Volunteers hand out inflatable noisemakers with blue-and-white Gauloises logos, green Repsol wristbands and ads for motorcycle insurance (the discarded flyers cre-

ate their own traction issues). Security guards check for glass, but turn a blind eye to airhorns and somehow miss enough fireworks to level a city. Guys dressed in diapers, bibs, construction helmets and adorned with oversized pacifiers lead the crowd in chants and try to initiate a wave.

A Jumbotron shows close-ups from the pit and follows the leaders around the circuit. Fans hoist flags on 20-foot fishing poles. Airhorns blast. Riders finish practice laps by doing long wheelies and burnouts that send up clouds of smoke. The fans respond with huge detonations of fireworks that send up even more acrid clouds of smoke. The guys in front of us roll spliffs with tobacco and hash. Rossi wins. Fans climb the fence and race across the track. Police herd them back. Fans throw bottles, batons, whatever, at the police vans.

In the parking lot afterward I watch women strip down to their lingerie, wrestle tan bodies back into riding leathers, climb aboard bikes and depart.

I recall that sketched bouquet of flowers back at that Barcelona pedestrian crossing, and I want to reach for it.

5 REASONS THIS IS THE LAST CYCLE WORLD GP EURO-TOUR

At our good-bye dinner I try to explain why good things have to come to an end, and offer a Letterman-style list;

1. Team Moron is faster than we are. (Well, maybe Canet or Hoyer could keep up, but who would put out the magazine?)

2. Ah, young Paduan, we have trained you well. You are now a Jedi Knight. (Most of the people on the tour are fully capable, i.e. the GPS guys who planned their own warmup tour.)

3. Everyone has memorized David Edwards’ 16 reasons you should ride a GS on an Edelweiss tour (reasons #10-16 “White Roads”)

4. With the USGP at Laguna Seca, we no longer have to go to Europe to feel normal.

5. We are looking for the next thing. And you will be invited.

James R. Petersen, for 30 years an editor at Playboy, has ridden a Norton for most of that time, either through loyalty, lack of imagination or the complete absence of discretionary income. This is his third appearance in Cycle World.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMiscellany

December 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsKing of the World

December 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCFire, Misfire

December 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2005 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's New Air-Bagger!

December 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupMonster Jugs

December 2005 By Mark Hoyer