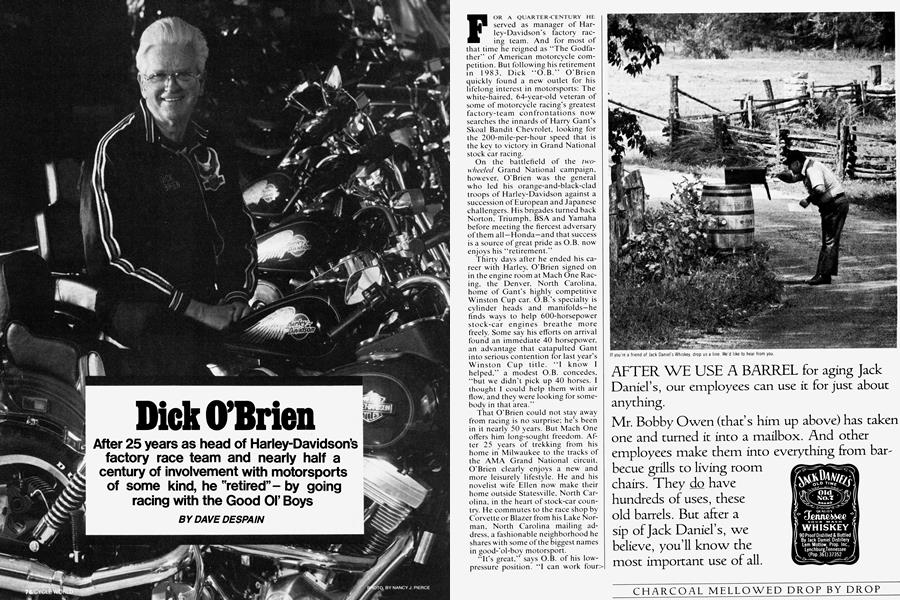

Dick O'Brien

After 25 years as head of Harley-Davidson's factory race team and nearly half a century of involvement with motorsports of some kind, he "retired" — by going racing with the Good 0I' Boys

DAVE DESPAIN

FOR A QUARTER-CENTURY HE served as manager of Harley-Davidson's factory racing team. And for most of that time he reigned as “The Godfather” of American motorcycle competition. But following his retirement in 1983, Dick “O.B.” O’Brien quickly found a new outlet for his lifelong interest in motorsports; The white-haired. 64-year-old veteran of some of motorcycle racing’s greatest factory-team confrontations now searches the innards of Harry Gant’s Skoal Bandit Chevrolet, looking for the 200-mile-per-hour speed that is the key to victory in Grand National stock car racing.

On the battlefield of the twowheeled Grand National campaign, however, O'Brien was the general who led his orange-and-black-clad troops of Harley-Davidson against a succession of European and Japanese challengers. His brigades turned back Norton, Triumph, BSA and Yamaha before meeting the fiercest adversary of them all —Honda—and that success is a source of great pride as O.B. now enjoys his “retirement.”

Thirty days after he ended his career with Harley, O’Brien signed on in the engine room at Mach One Racing, the Denver, North Carolina, home of Gant’s highly competitive Winston Cup car. O.B.’s specialty is cylinder heads and manifolds—he finds ways to help 600-horsepower stock-car engines breathe more freely. Some say his efforts on arrival found an immediate 40 horsepower, an advantage that catapulted Gant into serious contention for last year’s Winston Cup title. “I know I helped,” a modest O.B. concedes, “but we didn't pick up 40 horses. I thought I could help them with air flow, and they were looking for somebody in that area.”

That O'Brien could not stay away from racing is no surprise; he’s been in it nearly 50 years. But Mach One offers him long-sought freedom. After 25 years of trekking from his home in Milwaukee to the tracks of the AMA Grand National circuit, O’Brien clearly enjoys a new and more leisurely lifestyle. He and his novelist wife Ellen now make their home outside Statesville, North Carolina, in the heart of stock-car country. He commutes to the race shop by Corvette or Blazer from his Lake Norman, North Carolina mailing address, a fashionable neighborhood he shares with some of the biggest names in good-’ol-boy motorsport.

“It's great,” says O.B. of his lowpressure position. “I can work four> days a week if I want to. and that leaves me time to get in some fishing and boating. It’s a new challenge, it keeps me busy and I can pick up some extra scratch.”

"I'm proud of the XR?50 engine and the way it dominated flat-track racing. It really is a nice engine:'

Stock-car engine development is only the latest chapter in O’Brien's remarkable twoand four-wheeled competition career, a racing epic that spans nearly half a century. “I started out like a lot of kids back then,” he recalls of his formative years in the world of high performance as a Florida teenager. “You went and bought a jalopy out of a junkyard and started racing it. From there I went on to sprint cars, and I drove a few stock cars and was also helping the guys out with their engines.”

As O’Brien leapt with relish into the post-war racing scene, Daytona Beach became a motorsport Mecca— and his second home. “I drove the Daytona beach race twice in a stock car. I finished tenth once and didn't finish the other time. And I raced the Daytona 200—on Harley-Davidsons, of course—three times.

“The first time I went to the 200 was to watch in 1 938. The only one I missed was the first one in ’37,” he recalls, “and I didn't miss another one until last year, in 1984.” He laughs at the memory. “That was the only time since I came to Mach One that we ended up working on Saturday and Sunday, so I didn't get to go to the races!”

Though O.B. enjoyed some success as a racer, it was in the preparation of equipment, and later in the selection and coaching of riding talent, that he was destined truly to excel. “I found that I could build engines better than I could race,” he says with another laugh. “Those guys were goofier than I was.”

In 1957, while working for the Orlando, Florida, Harley-Davidson dealer—the race-crazy Puckett Motors, where five of the 15 employees did nothing but build race bikes— O'Brien got the call to go to Milwaukee, where he succeeded Hank Syvertson as head of the racing department. “1914 was when HarleyDavidson really started professional racing,” O’Brien recounts, a just pride creeping into his voice, “and from then until the time I left, there had been only three people in charge of racing. Each of us was there more

than 20 years. and I've got the lead with 26½: anybody who goes in there now is going to have to beat that." During O.B.'s long and prosperous watch, Harley-Davidson factory rid ers compiled an impressive record. winning the Grand National title a remarkable 16 times, including the year he retired. "I told John David son three or four years before I left," O'Brien recalls of his departure from the two-wheeled wars, "that when I reached 62, I was gonna be a gone> Jasper. I wanted them to start bringing somebody along to take my place. The other thing I wanted was to go out with the Number One plate.”

He got his wish. His 62nd birthday came in July of'83, and two months later, team rider Randy Goss claimed Number One; and on Halloween — “the day of the orange and black,” O’Brien laughs—he ended his unparalleled career with the factory. “I took 30 days off, then started to work here,” he says with another smile, surveying his new, four-wheeled surroundings. “I'd looked all over the country, considering where we might want to go, and I liked the mountains and the lakes down here. So I came down and bought a house in August, just before I left the factory.”

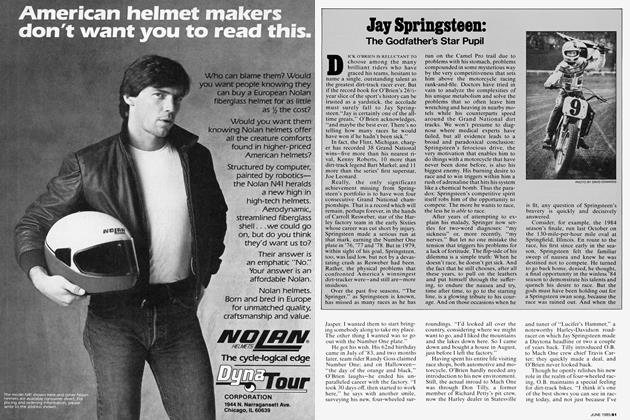

Having spent his entire life visiting race shops, both automotive and motorcycle, O’Brien hardly needed any introduction to his new environment. Still, the actual inroad to Mach One was through Don Tilly, a former member of Richard Petty’s pit crew, now the Harley dealer in Statesville and tuner of “Lucifer’s Hammer,” a noteworthy Harley-Davidson roadracer on which Jay Springsteen made a Daytona headline or two a couple of years back. Tilly introduced O.B. to Mach One crew chief Travis Carter; they quickly made a deal, and O'Brien never looked back.

Though he openly relishes his new role in the realm of four-wheeled racing, O.B. maintains a special feeling for dirt-track bikes. “I think it’s one of the best shows you can see in racing today, and not just because I’ve been in it. A of lot people I know in car racing have gone to a mile and said, ‘Jeezus, what a show you guys put on!’ They’re really charged about the whole thing. In fact, Travis watched one on TV the other day and said, ‘I’ll tell you, those boys put it in there.’ ”

Love of a good flat-track race notwithstanding, O’Brien doesn’t get to many motorcycle races anymore. That’s due in part to his work schedule at Mach One but primarily because five decades of chasing races has satisfied his yearning to be there for the drop of the green flag. A sheepish note touches the voice of the man who attended, rode or managed a team in a noteworthy 46 straight Daytona 200s. “Y'know,” he confesses, “I didn’t see a motorcycle race all last year. I do keep up with who’s doing what, and this year I had to call right after Houston to find out what happened in the opener. But I didn’t actually go to a race all last season.” Perhaps that is just as well. For had O.B. visited the ’84 Camel Pro Series,

he would have witnessed his beloved orange-and-black being devoured by the all-conquering Honda RS750 dirt-trackers, the machines that ended the 10-year reign of H-D’s XR750 as the King Kong killer-bike of American dirt-track racing. “I’m very worried about that set-up,” O’Brien says of Harley’s recently restructured racing team, which this year attempts to fend off the Japanese while confronting monumental budget problems. In fact, O'Brien was called back to the factory as a> consultant last December 7 —the ironic significance of the date is not lost on him—to help evaluate his old team’s options for the future.

In the short term, O’Brien does not share the doomsayers’ view that the Harleys are destined to lag far behind the technologically superior Hondas. “Harley can be fairly competitive with what they've got,” he contends, “if they go ahead with the development of the present engine, change the power curve and the rpm band, and come up with a little better-handling chassis.” But long-term, O.B. fears a root problem confronting the Milwaukee V-Twins and their factory program of support. “What hasn’t been done in the last year is development,” he says a bit sadly. “It’s OK to be a little lax if you're winning, but when it comes down to what it is now, you pull out the stops and run wide-open. But you’ve got to have the people and the money to do it.”

Having recently migrated from a race team strapped for money to a shop operating near the pinnacle of perhaps the richest motorsport series in America—the Winston Cup stockcar tour—O’Brien sees ample opportunities for his old friends from the bike world. “I think any top Expertranked motorcycle racer could make it in the automobile thing,” he says matter-of-factly. “And when a guy starts sliding over the hump, he should think NASCAR. This is where the money is and where the competition is, and I think it’s one of the safest racing sports in the world. A

guy can make a good living and keep racing right on up into his 40s.”

In that vein, O.B. subscribes to the belief that a racer is a racer is a racer. “I really don't see any difference,” he observes, “between motorcycle and automobile racers. It’s the same thing, and you find the same hangups. Some of them are cool, calm and

collected, and some of them aren’t. They’re just people.” If there is a significant difference between the car guys and the bike guys it is age. “With motorcycles,” O’Brien points out, “you're dealing with kids—16and l 7and 18-year-old people. These stock-car boys are in their late 20s, 30s and 40s, headed towards 50 and still out there going like a son-ofa-gun.”

The age difference points to another distinction O’Brien would draw between the two fraternities. “A lot of young kids don’t feel PR is important, but the automobile guys are a lot more grown-up in that regard and realize how important it is to their future. But no matter where you go in racing, they’re all good people,” he concludes. “To me, at least, it’s always been that way.”

The “good people” with whom O’Brien has worked during his unprecedented tenure in motorcycle racing include a pantheon of the alltime legends, names like Joe Leonard, Carroll Resweber, Bart Markel and, most recently, Jay Springsteen. There’s really no way to compare the greats,” O.B. says of the superstars he’s tutored. “So many things are different from one generation to the next. The equipment is so much better today and today’s riders have a lot more races on the schedule, so their career win records are more impressive. But I think the great riders would have been great in whatever era they raced.”

And what traits did “The Godfather” of dirt-tracking, the man charged with the responsibility for doling out those precious H-D factory-rider contracts and engine parts, seek out in selecting his annual stable to wear the orange-and-black? “You look for that determination,” O'Brien answers, “for that extra drive that only a very few people are fortunate enough to have. And the great ones have not only the drive but also the ability. Some people have one or the other, but you’re looking for both, the ability and the drive, in the same guy.”

For all his fond memories of the greats and the near-greats who populated his race teams over the years, O'Brien is quick to admit a special feeling for one: Cal Rayborn. “We were very close to Cal,” he admits. “He was a special individual. You could never stay mad at Cal for more than 10 minutes. He’d always say something that would crack you up. It was an awful blow to us,” he says softly, “when Cal was killed.”

"I think any top Expert-ranked motorcycle racer could make it in automobile racing'

continued on page 86

continued from page 84

Rayborn’s death, while testing a Suzuki following Harley’s virtual pull-out from roadracing, points up a risk team managers face by building friendships in a business marred by periodic tragedy. “You can’t help but get close to the guys,” he says. “You can’t run with these people four or five years and meet their wives and their kids and stay at their houses and eat with them and travel with them . . . how the hell are you gonna keep from getting close? It just happens. I’ve had the feeling of wanting to get out of racing because something happened to somebody. But then you stop and realize that your leaving won’t stop anyone from racing. Probably the best thing you can do is try to build the best and safest equipment for them to ride. I guess that’s the way you try and justify it to yourself. At least that’s the way I justified it.”

It is fitting that Rayborn contributed significantly to one of two achievements that O'Brien rates as his premier career accomplishments. “Two things stand out,” he says proudly, surveying his quarter-century in motorcycle racing. “One was the design and development of the XR750 engine and the way it dominated dirt-track racing for so many years. It’s really a nice engine. But the most thrilling moment for me in all of racing was in 1969 at Daytona, when all those Harleys went around the racetrack together on the first lap. It looked like a squadron of airplanes about a quarter-mile ahead of everybody else. We had seven machines there that year and six of them came by all together. The year before we’d been beaten down there, and we put in one of the hardest years in history working on the engines and in the wind tunnel. Cal went on and just annihilated the place, winning by about a lap-and-a-half and becoming the first rider ever to average 100 miles an hour there. I really don’t know why, but that was my biggest thrill, even better than getting Number One.”

As Dick O’Brien surveys his latest racing surroundings, a highly-accomplished stock-car shop nestled in the pastoral beauty of rural North Carolina; as he savors the memories of an extraordinary career and adds daily to their inventory, he moves toward a conclusion and grins at its simplicity even before it is drawn. “It’s all the same,” he smiles. “It’s all racing. These fellows just have a couple more wheels.” S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialCountering the Steering Myths

June 1985 By Pauldean -

At Large

At LargeInside the Accidental Fortress

June 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1985 -

Rounup

RounupLand Closure: the Fight For the Open Range

June 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupWave Bye-Bye To Street Hawk

June 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe World's Largest Gas Tank

June 1985