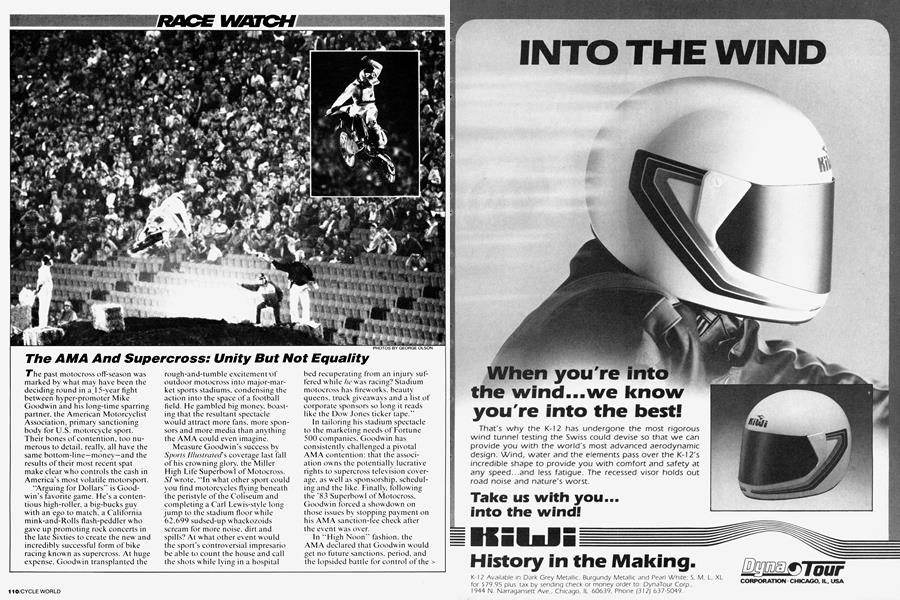

The AMA And Supercross: Unity But Not Equality

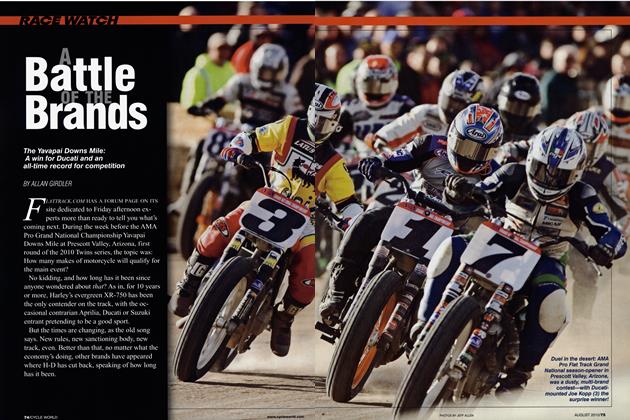

RACE WATCH

The past motocross off-season was marked by what may have been the deciding round in a 15-year fight between hyper-promoter Mike Goodwin and his long-time sparring partner, the American Motorcyclist Association, primary sanctioning body for U.S. motorcycle sport. Their bones of contention, too numerous to detail, really, all have the same bottom-line—money—and the results of their most recent spat make clear who controls the cash in America’s most volatile motorsport.

“Arguing for Dollars” is Goodwin's favorite game. He’s a contentious high-roller, a big-bucks guy with an ego to match, a California mink-and-Rolls flash-peddler who gave up promoting rock concerts in the late Sixties to create the new and incredibly successful form of bike racing known as supercross. At huge expense, Goodwin transplanted the rough-and-tumble excitement*of outdoor motocross into major-market sports stadiums, condensing the action into the space of a football field. He gambled big money, boasting that the resultant spectacle would attract more fans, more sponsors and more media than anything the AMA could even imagine.

Measure Goodwin’s success by Sports Illustrateds coverage last fall of his crowning glory, the Miller High Life Superbowl of Motocross. SI wrote, “In what other sport could you find motorcycles flying beneath the peristyle of the Coliseum and completing a Carl Lewis-style long jump to the stadium floor while 62,699 sudsed-up whackozoids scream for more noise, dirt and spills? At what other event would the sport’s controversial impresario be able to count the house and call the shots while lying in a hospital bed recuperating from an injury suffered while he was racing? Stadium motocross has fireworks, beauty queens, truck giveaways and a list of corporate sponsors so long it reads like the Dow Jones ticker tape.”

In tailoring his stadium spectacle to the marketing needs of Fortune 500 companies, Goodwin has consistently challenged a pivotal AMA contention: that the association owns the potentially lucrative rights to supercross television coverage. as well as sponsorship, scheduling and the like. Finally, following the '83 Superbowl of Motocross, Goodwin forced a showdown on those issues by stopping payment on his AMA sanction-fee check after the event was over.

In “High Noon” fashion, the AMA declared that Goodwin would get no future sanctions, period, and the lopsided battle for control of the money in supercross was on. That battle didn’t last very long. The ’84 season opened with the news that Goodwin had joined forces with other race organizers to form InSport, the promoter-owned, pseudo-sanctioning body that organized last year’s supercross series. The AMA’s attempt to counter with a series of its own mustered just three dates, one of which was later canceled and another boycotted by the factory teams. Goodwin had won a convincing victory, and the AMA was effectively out of the supercross business.

Then, in the aftermath of that power struggle, the picture changed again. Quiet negotiations late in ’84 were followed by the surprise announcement that the 1985 InSport Supercross series will be AMA-sanctioned. Have the dog and the cat, the snake and the mongoose, Goodwin and the AMA really made peace? Apparently so, for now, but the terms of that settlement redefine the AMA’s relationship with race promoters.

Explanations of the reconciliation vary. AMA Competition Director Wayne Moulton figures it came about in part because the InSport people found that running a sanctioning body was more work and cost more money than they expected. Former InSport Competition Director Gary Mathers, now raceteam manager for American Honda, agrees that may have been a factor but thinks the real reason InSport chose to negotiate was that the AMA simply caved-in on all the significant money issues.

In truth, the sanctions that the AMA now issues for so-called “InSport Tour” races are substantially different from those in other forms of professional racing.

InSport, which is quartered in Goodwin’s California offices, retains authority in such crucial areas as TV rights, sponsorhip and scheduling— the realms where the big money is made. The AMA’s role is essentially limited to officiating on the racetrack.

Whether such changes are in the sport’s best long-range interests remains to be seen. For example, the supercross riders, those hardy souls who bruise their bodies for the pleasure of the “whackozoids,” have consistently and logically argued that they should share more generously in the success of the sport. Recalling the AMA/InSport split, Moulton says the AMA’s insistence on more rider prize money was a major sticking point.

“We asked for a minimum purse of $35,000, but they didn’t want any part of that. In fact, one of the first things InSport did was lower the purses,” Moulton contends.

History must now judge how equitably the spoils of supercross success will be divided. For its part, the AMA is tickled to be back in the ballgame, while Goodwin and the rest of the sport’s promoters are busy flexing their newly acknowledged, and AMA-blessed, right to negotiate their own deals and to profit accordingly. A decade-and-a-half of infighting is over; and Mike Goodwin, the controversial inventor of supercross, is officially calling the shots regarding the sport’s future.

Dave Despain

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialA Matter of Opinion

March 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1985 -

Departments

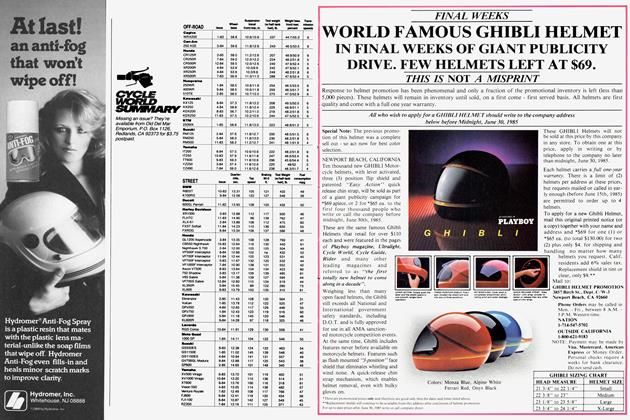

DepartmentsSummary

March 1985 -

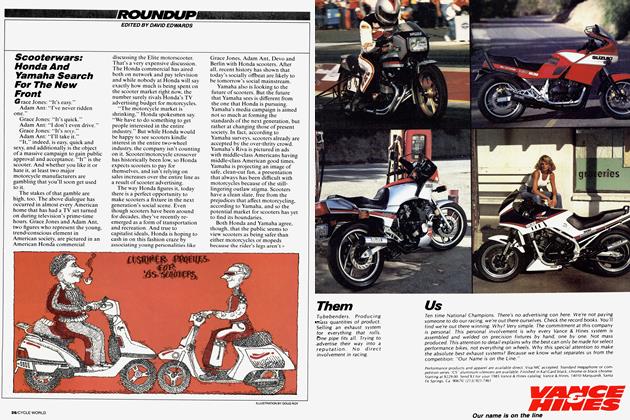

Roundup

RoundupScooterwars: Honda And Yamaha Search For the New Front

March 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupThe $590 Million Engine Rebuild

March 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThree-Wheeling, British-Style

March 1985