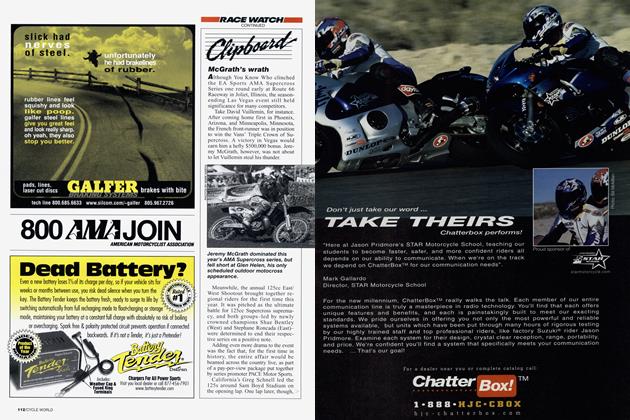

Clipboard

RACE WATCH

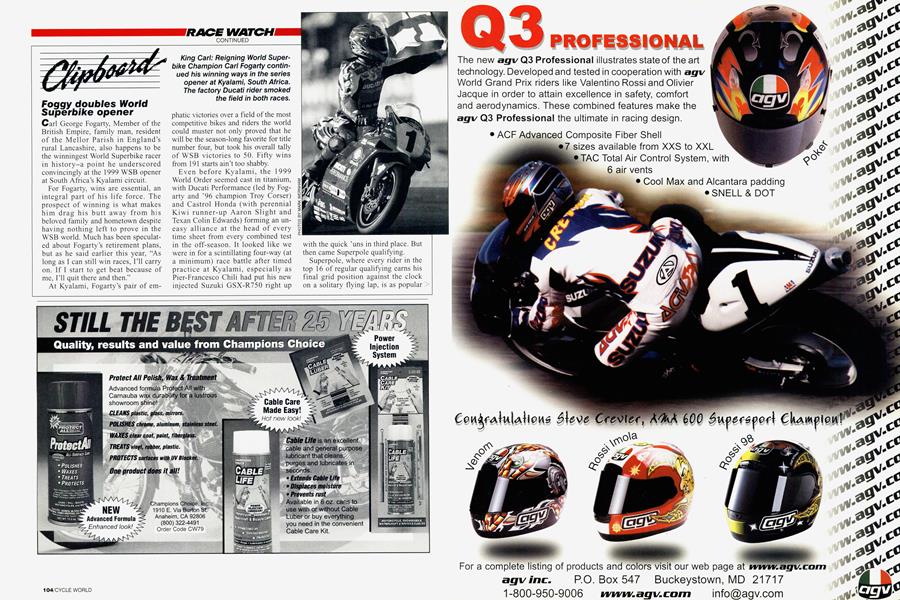

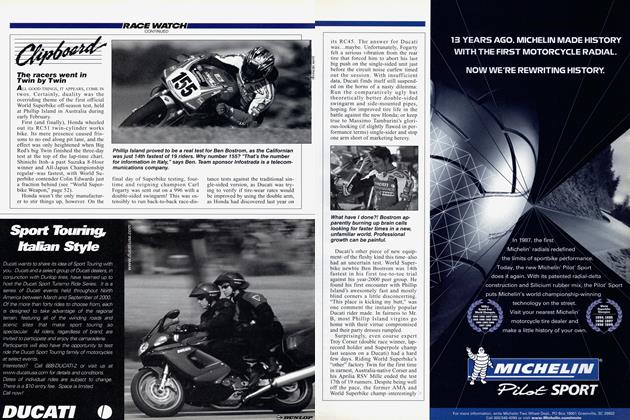

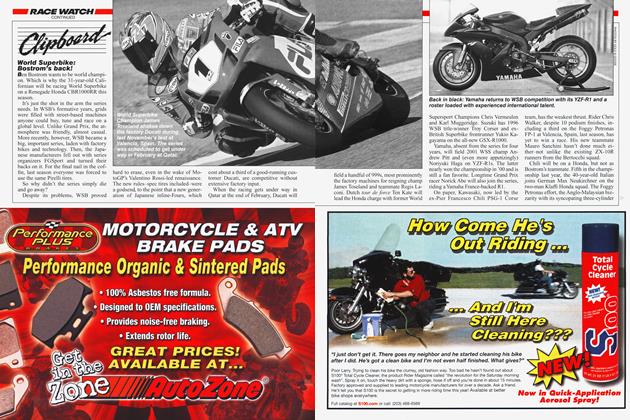

Foggy doubles World Superbike opener

Carl George Fogarty, Member of the British Empire, family man, resident of the Mellor Parish in England’s rural Lancashire, also happens to be the winningest World Superbike racer in history-a point he underscored convincingly at the 1999 WSB opener at South Africa’s Kyalami circuit.

For Fogarty, wins are essential, an integral part of his life force. The prospect of winning is what makes him drag his butt away from his beloved family and hometown despite having nothing left to prove in the WSB world. Much has been speculated about Fogarty’s retirement plans, but as he said earlier this year, “As long as I can still win races, I’ll carry on. If I start to get beat because of me, I’ll quit there and then.”

At Kyalami, Fogarty’s pair of emphatic victories over a field of the most competitive bikes and riders the world could muster not only proved that he will be the season-long favorite for title number four, but took his overall tally of WSB victories to 50. Fifty wins from 191 starts ain’t too shabby.

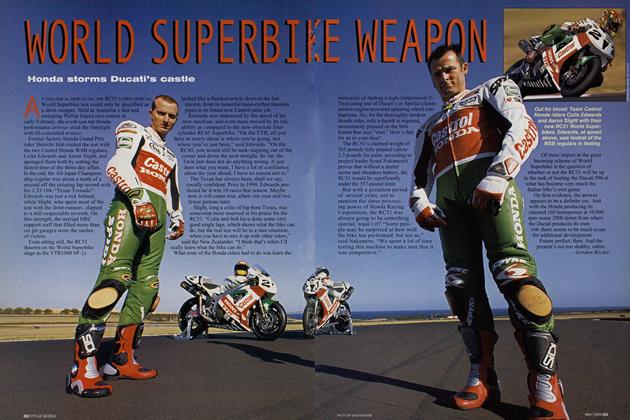

Even before Kyalami, the 1999 World Order seemed cast in titanium, with Ducati Performance (led by Fogarty and ’96 champion Troy Corser) and Castrol Honda (with perennial Kiwi runner-up Aaron Slight and Texan Colin Edwards) forming an uneasy alliance at the head of every time sheet from every combined test in the off-season. It looked like we were in for a scintillating four-way (at a minimum) race battle after timed practice at Kyalami, especially as Pier-Francesco Chili had put his new injected Suzuki GSX-R750 right up with the quick ’uns in third place. But then came Superpole qualifying.

Superpole, where every rider in the top 16 of regular qualifying earns his final grid position against the clock on a solitary flying lap, is as popular with top WSB racers as “Fidel Rules” T-shirts are at a Cuba Libre rally. No one needs the added pressure, and it transpired that Chili needed it less than anyone, botching his lap to end up on the fourth row at one of the most difficult-to-pass-on circuits on the 13-event 1999 WSB calendar.

This was a major contributor to Chili’s lowly finishing positions-that and the GSX-R’s eternal ability to bewitch and beguile all scientific approaches to tame its unquestioned abilities. Team Alstare Corona Extra Suzuki threw out three years of knowledge with the Harris Performance bathwater at the end of ’98 (including a complete rider change), so it may take the new boys a bit of time to get up to speed.

One area the Belgium-based team unquestionably leads the rest is in paddock presence. No fewer than 27 bodies were conscripted to service the needs of four 750 and four 600 Suzukis at Kyalami, all working out of a pit garage the size of three basketball courts, every inch of which was tinged, hued or outright painted with the sponsor’s distinctive blue-and-yellow branding. Inflatable beer bottles, indoor and outdoor gazebos, an allday chef on hand frying improbably vast quantities of local meat and fowl-the Alstare Corona boys had it all. Oh, and free beer, too.

Only one other team in the championship has as many bikes as the Belgians, at least in official terms: Castrol Honda. Last year, the RC45 was going nowhere at Kyalami; this year. Slight was a match for anyone except Fogarty, taking a third and a second, allowing Honda to cross off another of the RC45’s occasional bogey circuits. There’s no question that the V-Four isn’t even close to the end of its development life, because every year Honda just keeps on pumping more steroids into the engine and engendering the chassis package with more consistency.

Even Colin Edwards has overcome his initial dislike of the RC45’s frontweighted handling characteristics, aided by more predictable Michelins and a new remote-reservoir front suspension (now allegedly with springloaded pistons inside the reservoirs that deflect backward when fork pressure increases). A brave starter at Kyalami, Edwards is gagging to have a go at the world when his shoulder, badly smacked at Laguna Seca in final testing, gets better.

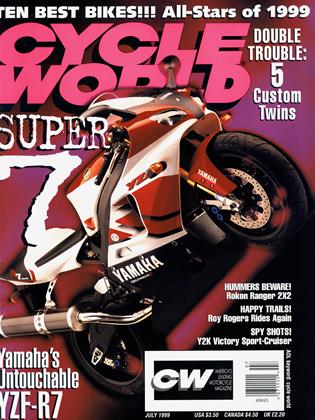

There seemed to be two races at Kyalami: one for the works Michelin runners and one for the rest. Noriyuki Haga, now a freshly vulcanized Michelin man after years on Dunlops, was way up front on Yamaha’s latest wonder-weapon, the YZF-R7, until he lost pace with first-race podium finishers Fogarty, Corser and Slight. Haga then lost the plot entirely in race two, to crash gloriously and comprehensively while staving off another attack from the chasing Slight. Top spectator value as ever. Haga has shown that the R7 is a very fine racing motorcycle, which may just develop into every other team’s worst nightmare when it delivers even more engine than it already has.

The other completely new bike in WSB is the Aprilia RSV Mille, a loner with its 60-degree V-Twin engine configuration. The Noale firm’s effort was rewarded with one DNF (due to a little too much speed during the bitch-flicking phase from lone pilot Peter Goddard) and a mighty fine seventh after a spirited effort from the same guy in race two. Two good top-10 finishes would have been nicer, but as a brand-new factory team, on what appeared to be uncompetitive Dunlop race rubber, you have to yell, “Bravo!” Goddard may be entirely realistic in his claim that a podium will be his before season’s end.

The happy vibes from the Aprilia pit were not so evident in the garage of the Eckl Kawasaki team. Overall results were respectable enough, with Akira Yanagawa and 1998 privateer of the year, Gregorio Lavilla, finishing the day in fifth and sixth in the championship table. But as was evident from the Grand Canyon of a gap between them and the top four or five guys, there is a lot of work to do if they want to have a realistic go at winning the world title this year.

Unless you take Eckl’s World Supersport 600 team into consideration, because it got off to a winning start, much to everyone’s surprise. Maybe “team” is actually too strong a word, because a couple of mechanics and one rider, Scotsman lain MacPherson, hardly constitute a WSS team in this year’s championship.

Sadly, possibly the best South African rider of his generation, Brett MacLeod, suffered fatal injures on the opening lap of the subsequently halted first Supersport race. The youthful MacLeod had been talent-spotted by Kenny Roberts and had ridden the Modenas Triple at the pre-season IRTA tests at Jerez. MacLeod’s death, in a pure racing accident that saw two other riders, Davide Bulega and Massimo Meregalli, go down injured, cast a sad pall over the second Superbike race once the news was made official. It also served as an unnecessary reminder that however much we all love motorcycle racing, sometimes it exacts the ultimate price, regardless of what safety measures we take. A sad opening to what we can only hope will be a happier, more competitive World Superbike season. -Gordon Ritchie

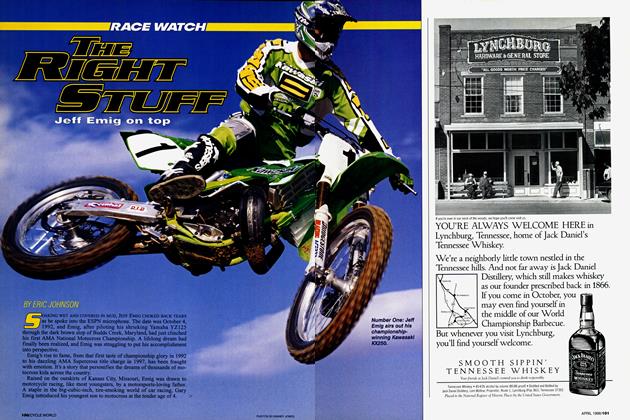

LaRocco (quietly) gets the job done

In the eyes of hardcore Supercross fans, 1999 was to be The Year of the Supercross Youth Movement. Intoxicated by the thought of snatching away Jeremy McGrath’s Number-One stadium plate, Team Honda opened up the war chest to finance a team of young lions. The Red Riders included three former AMA 125cc Supercross Champions-Kevin Windham, Mickaël Pichón and Ezra Lusk-and former 125 and 250cc World Champion Sebastien Tortelli.

Not since the motor giant’s halcyon era (1984 with David Bailey, Johnny O’Mara, Ron Lechien and Bob Hannah) had so much money and effort been earmarked for motocross. Not to be outdone, Kawasaki lured teen-sensation Ricky Carmichael into the factory mothership, hoping the 125cc whiz kid could inflict damage on the McGrath dynasty.

But somehow it’s gone wrong for the marauding group of kids who were so keen to burn down the house that Jeremy built, a courtesy of crashes, injuries and sub-par finishes.

Oldster Mike LaRocco, though, has grabbed another gear. A two-time AMA champion, the 28-year-old native of football-loving South Bend, Indiana, prepared for the 1999 campaign with a quiet confidence honed razor-sharp from a decade of banging bars on the Pro circuit.

It was the ’98 season that gave the battle-hardened racer a new lease on life. As a member of the Suzuki factory team during the 1996 and ’97 seasons, LaRocco struggled with team politics and off-song equipment. In a fortuitous stroke, he hooked up with Rick Zielfedleer of Factory Connection (an East Coast hop-up shop), who was putting together a Honda satellite effort with Jack in the Box sponsorship. After the ’98 campaign, LaRocco and the team embarked on a comprehensive winter testing program.

“I was satisfied, but not overly happy with my 1998 season,” LaRocco said while taking a break from etching out a new practice track near his home. “I podiumed once in Supercross and a few times in the nationals, but I knew I could have done better. I felt really good before this season started because we tested really well, and Honda stepped up to provide more help. I also felt a lot stronger because this was the first time in five years that I didn’t have to have surgery during the off-season.”

With mechanic Paul DeLaurier and personal manager Fred Bramblett by his side, LaRocco rolled into Anaheim, California’s Edison Field for the first round of the series. Lined up against the most competitive field in U.S Supercross history, he hoped for the best. “I knew it was a tough, very broad field,” he conceded. “I didn’t know what to expect. I just wanted to go out and do my best.”

When the curtain dropped later that evening, LaRocco had finished third and found himself on the podium spraying champagne with teammates Lusk and Pichón. “I felt really good about my riding, and I knew then that it was all going to start rolling,” he says.

And roll it did. While outshined by the hyped-to-the-hilt McGrath/Lusk duel, LaRocco pulled off three more consecutive podium finishes in San Diego, Phoenix and Seattle. And it was just about that time that the wheels began to come loose on the “youth brigade” miracle machine. Possessed in his quest to beat McGrath, Lusk began to hit the dirt on a regular basis. Pichón, while finding himself on the podium on a few occasions, battled with inconsistency. Windham, in his first year with Team Honda, struggled to come to terms with his new CR. Carmichael has ended up on his head on far too many occasions.

“These guys have been fast-very fast,” LaRocco said. “However, Carmichael has been too aggressive for the 250, though he’s starting to figure it out. Same thing with Lusk; sometimes he just tries too hard. Windham took a while to get going, but then he became very fast and confident. Before he got injured (at Minneapolis), I think he was becoming too confident in his riding. The young guys just go too fast at times.”

Twelve races into the 1999 AMA Supercross series, LaRocco has garnered a total of seven top-three finishes, maintains an eyebrow-raising 4.4 average finishing position and sits a very comfortable second in the series point standings. Despite his excellent on-track form, however, the soft-spoken Hoosier has yet to pull off a stadium victory this season. His last was aboard a Kawasaki in April, 1995, at the Pontiac Silverdome.

“I definitely have a goal to win a race this year,” he proclaims. “I have had a number of good races, and the only goal 1 have left this year in Supercross is to be on top of that podium.”

Lauded for his ultra-aggressive natural-terrain skills, LaRocco also has a genuine shot at winning his third outdoor national championship. “Outdoors is better for me. The tracks are larger and the motos longer, which helps me make up for my notorious poor starts. I have a good chance for the title and that’s my goal: I want to be the big gun in the class,” he states.

In what was to be The Year of the Kid, LaRocco is an interesting study in the dynamics of motocross racing. Older than most of his factory-supported competitors, somewhat battered and bruised from a number of injuries, he’s ridden the emotional roller coaster of professional motocross many times.

“In 1996, it was not going well and I thought, ‘Man, I’m done.’ After I left the Suzuki team at the end of the 1997 season, I had nothing going, nor could I get anything,” LaRocco says. “Now, I feel so great that quitting is the last thing on my mind. If I continue to feel as good as I do now, I see myself going on because I really enjoy riding and training. I don’t see an end to this.” -Eric Johnson

“Coach” Schwantz

After a couple of stormy seasons in NASCAR’s Busch Grand National series, Kevin Schwantz is back on two wheels-as a coach. The 1993 500cc World Champion has joined forces with Fast By Ferracci’s Larry Pegram, who approached Schwantz last year. The former flat-tracker was riding a Yoshimura Suzuki TL1000R, but wanted another shot at a Ducati. “Larry asked me to help him,” Schwantz says. “He thought Ferracci would take a chance on him if I was there for motivation.”

It worked. Pre-season testing went well, and at Daytona Pegram qualified fifth, then suffered from brake problems during the race and finished ninth. “At Daytona, you just try to persevere,” Schwantz says. “If you can make the bike go around the track without wobbling, everybody gets through the infield at about the same pace.”

Two weeks later, at Phoenix, Pegram qualified 11th, ran as high as fifth, then lost a couple of positions at the end. “Considering how badly he’d been hurt there in ’93, I thought he did a pretty good job,” Schwantz opines. “I’d like to think Larry could get on the podium a couple of times this year, maybe even win a race.”

It won’t be easy. “I think the level of competition is as good as it’s ever been,” Schwantz says. “In 1987, when I was racing here, there were two or three guys who might winFred Merkel, Wayne Rainey and me. Now, there are a half-dozen guys who stand an honest chance. And there are another half-dozen guys with factory bikes who could put themselves up front if something were to happen.” Don’t look for Schwantz to suggest major chassis changes. “I don’t feel like that’s really my position,” he explains. “Besides, I’m not a setup man.

I wish I’d paid more attention to setup when I was racing, but I had my hands full with track stuff, knowing where to be and what to do every lap.

I didn’t need to be thinking about clicks and springs and oil and offset and things like that.”

Schwantz spent his entire professional career with Suzuki, and even though he retired five years ago, many still associate him with the Japanese manufacturer. “I’m still good friends with all the guys at Yoshimura and American Suzuki,” Schwantz admits. “We’re talking about trying to find a place within Suzuki for me. I’d like to be more involved on the development side, possibly picking kids to put in the Supersport program.

“Lately, it’s been nothing but Australian, English or whatever in World Superbike and Grand Prix-there haven’t been many Americans. I’d like to think that’s going to change. We’ve got a good group of young kids who have the ability. If I can give somebody an advantage, maybe that will help him go on.”

Matthew Miles

Britten back in business

Tantalizing rumors aren’t enough. We want to know what’s really been happening at Britten Motor Company since John Britten’s death from cancer in 1995. We’d heard other makers had taken a look and pronounced the innovative VI000 racer uneconomic to produce. Some team members had left-at least one to help with the new Auckland-built BSL 500cc GP Triple. With the completion of the last in the series of big V-Twins, would the operation fold to become history?

Not according to Wayne Alexander, head of the present four-man team working at Britten. “We’re getting a base, so we can stand on our own two feet,” he said. “Our strength was always our ability to do the engineering on a shoestring. I don’t think a solution will come from outside. I think the solution is here.”

The team is working on a spin-off of the radical Single that Britten was designing at the time of his illness. A lightweight Thumper, it’s intended for speedway, short-track and possibly motocross.

The last time I spoke with Britten, he told me that although he couldn’t yet say much about the Single, it included “interesting” features. Now, I discover that the prototype motor’s cylinder and head were in one piece, eliminating the weight and bulk of head bolts, as in the very latest Formula One car engines. Six valves were used-four intakes and two exhausts-with three sparkplugs. As an engine’s bore is made larger to accommodate greater valve area, its stroke grows shorter, and the resulting pancake-shaped combustion chamber burns too slowly for efficiency. More mapped ignition points prevent this.

Two of the four intakes (the outside pair) were sized, shaped and timed for low-to-mid power. High-velocity flow through them would generate combustion-chamber turbulence for efficient burning at lower revs. Each intake had its own fuel injector, with its own fuel map. The inner pair and their injectors throttled up at higher revs to supply top-end airflow. These six valves were operated from only two camshafts without rocker arms, through the use of unique oblong or oval tappets. This was Britten’s experimental approach to the problem other makers now are tackling with complex variable-valvetiming systems: How to get a full spread of torque from bottom to top revs? Traditionally, top-end engines with big intake area stumble at lower revs, while those optimized for lowspeed torque fade at higher revs. Britten wanted to have it all.

The engine ran on the dyno just two weeks after Britten’s death, making a reputed 88 horsepower on the first test series, from 605cc. Britten intended to explore, with later versions of this design, such things as carbonfiber composite cases and connecting rod. Only now are F-l race car constructors experimenting with carbon gearbox housings. Britten was never shy about innovation.

This project had been sparked in part by seeing the Vertemati four-stroke MXer in 1993. The team’s current work relates to the popularity of speedway in Australia, and while members were in Daytona this spring they spent Friday and Saturday nights at the Daytona short-track, “having a look round.”

The current development project employs just four valves but retains the reversed, intake-forward, exhaustbackward orientation of the original Single. The goals are light weight, high power and engine/chassis integration. “Our ability to build race equipment is our strength,” Alexander continued, “so it makes sense to stay in the motorcycle game.”

He was saying this because, in the last couple of years, company survival has meant taking in other work, such as development of a carbon-fiber propeller and fabrication of prosthetic parts for amputees. Britten was not the only one in the group with ideas. Those who remain knew him and his ways well. They know how ideas grow when several minds play pingpong with them over time. “John did leave ample material (to work from),” Alexander went on. “The creative process is flowing again.”

Britten Motor Company is back, and the goal for now is “a nice little lightweight Single.” We miss John Britten, but we’re glad his work is continuing.

Kevin Cameron

Seeling super-quick at NHRA opener

Angelle Seeling wasted no time at the NHRA Pro Stock drag-racing season opener in Gainesville, Florida, winning the event and setting a new record in the process. The 29-yearold defeated John Smith in the final round and also posted a new national low-E.T. mark of 7.212 seconds on her Team Winston Suzuki.

Though he finished second to Seeling, Smith managed to set a new national speed record during the event, hitting 192.22 mph in the quarter-mile. Defending NHRA Pro Stock Champion Matt Hines ended up third-the victim of chassis and engine troubles.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue