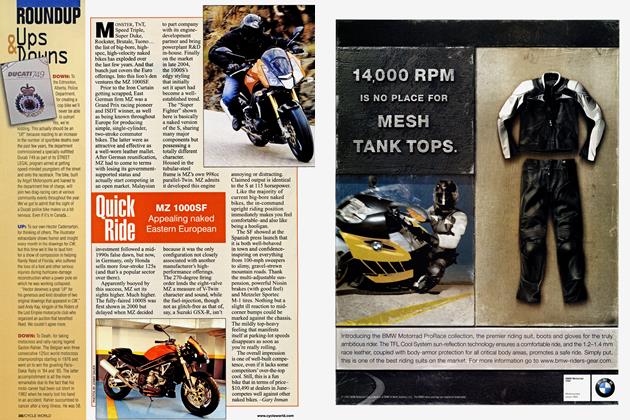

Clipboard

RACE WATCH

Foggy’s new Superbike

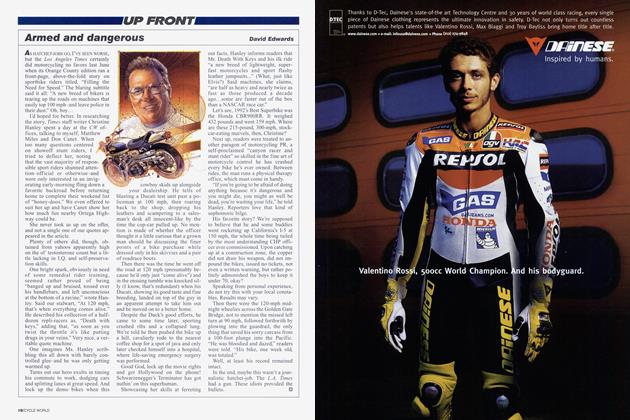

He was a hero the likes of which World Superbike racing had never seen, and his name became synonymous with Italian factory Ducati. So much so, in fact, that when injury forced his retirement from riding in 2000, it was half expected that he’d be put in some “managerial” position of esteem within the racing effort such as Mick Doohan has assumed with Honda.

But the wild-eyed four-time world champion set his sights higher, and decided to become his own motorcycle manufacturer.

Okay, that may be stretching things a bit, but when Malaysian oil giant Petronas decided it wanted to go Superbike racing in September of last year, it turned to Carl Fogarty to run the team, and lend his still-shining star power to the project. And so the Foggy Petronas Superbike was born.

Originally designed for use in the

four-stroke MotoGP series, the machine was to be converted to a full-spec Su perbike, and sold in streetbike form at

the earliest opportunity. In December last year, the first real work started on molding the three-;

cylinder beast into a finished motorcycle, ready for competition at the Brands Hatch WSB race-all being well.

To do this, the required road-going 75 bikes had to be completed by the June 30th deadline for FIM mid-season

homologation. No small feat, and nothing of its like had ever been tried before. But on June 11th, the Foggy Petronas FP1 racebike was unveiled in London, looking every inch the finished product, with an engine nestled away behind the capacious radiator and carbon-fiber bodywork. As the bike itself attested, Foggy’s boys, including ex-Team Roberts tech Nigel Bosworth, had completed their initial part of the project on schedule.

Whether or not the engines at the launch-the responsibility of former GP racer Eskil Suter-were runners or not, and whether streetbike project engineering company MSX had been able to make the required 75 machines in time at its English production facility (despite the bike being marketed as the first Malaysian Superbike-although the next ones will be manufactured in Malaysia) is unknown at presstime. One thing, however, is sure: Even getting to this stage of development of>

having just the two racebikes on show at the London launch in six short months is impressive.

The levels of design, fit and finish of the machine are remarkable, to say the least, and the short spec is that it runs an 899.5cc displacement (the maximum allowed for a three-cylinder in WSB), has 88.0 x 49.3mm bore and stroke, 14.0:1 compression, a claimed 185 horsepower at the crank at 13,500 rpm and 77 foot-pounds of torque at 11,000 rpm.

Sleeved down from its original 990cc guise, the FP1 has been redeveloped to be reliable as a roadbike and a racebike. Of course, a running prototype has yet to be seen. A test at Alméria, Spain, was to be the first airing of the machine on track, and-shooting for the moon as they are-the team expected that it would race at Brands Hatch, last-minute disasters aside.

A huge degree of effort has gone into optimizing the aerodynamics of the machine, with a single air intake in the pointed nose feeding a reverse engine layout, with the throttle bodies facing forward, and the convoluted exhausts facing the rear.

If the bike’s speed around the track meets the pace of development and execution so far, then a serious new player will really have arrived on the block. Especially with ’96 world champ Troy Corser and British Superbike charger James Haydon on board as riders.

The most ambitious project in the history of bike racing and roadbike manufacturing? Difficult to find another project to match it, whether it wins, loses or withdraws. -Gordon Ritchie

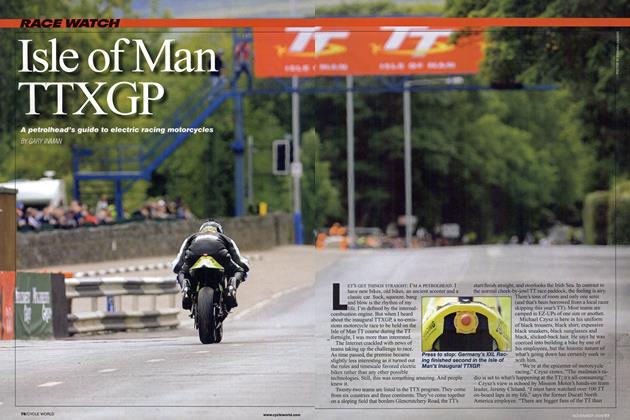

The TT returns, and the debate rages on

After all the Isle of Man TT has endured since its 1907 debut, it’s ironic that a disease that targets cattle finally, but temporarily, put the races on hold last year. The TT survived having its Grand Prix status stripped away, having the established international roadracing stars turn their backs on the place, and the countless attempts from external bodies to have the races stopped once and for all for reasons of safety. But the two-week festival of motorcycling, held on a speck of land in the middle of the Irish Sea, couldn’t withstand the hoof-and-mouth >

epidemic that decimated Britain’s livestock population. The races were sacrificed to stop the tens of thousands of visitors from bringing infectious spores

from the mainland with them.

In the interim, the TT also suffered one of its biggest-ever setbacks. The Isle of Man’s favorite adopted son, King

of the Mountain, winner of 26 TT races, Joey Dunlop, was killed in an obscure roadrace in the former Soviet Union a few weeks after the 2000 TT. The famous race meeting certainly had a lot to deal with this year...

But initial worries that TT visitors might have found a new summer vacation destination were quickly dispelled. Some 40,000 motorcyclists sailed from Ireland and England and the rest of Europe to renew their love affair with the place. Also on hand were 275 racers from 14 different nations, entered to ride the 37.73-mile public-road circuit. Everything looked good, and even the sun came out!

TT classes include those for Ultra Lightweight 125s through to 600cc Supersport bikes and even sidecars, but the real excitement is saved for the lOOOcc Fours of the Formula 1 and Production lOOOcc classes. This year saw Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha go>

head-to-head for top honors.

Every year, Honda plows a significant amount of money into sponsorship on the social side of the TT as well as its multi-pronged racing effort. You could be mistaken for thinking Big Red had taken over the island, but this year a Yorkshireman riding a brace of Suzukis spoiled the party. David Jefferies used his construction-worker build to keep on top of his rampaging GSX-R1000 to break the outright lap record in the F-l race with the first sub-18-minute/over126-mph lap. He then went on to win the Production lOOOcc race in spite of his transmission sticking in third gear on the last lap, and the Senior TT, during which he raised the lap-record speed to 127 mph.

Jefferies had won six TTs before this year’s haul of three elevated him to the status of TT great. There’s no doubting he’ll command a healthy paycheck to return next year.

One man who will be rooting around the back of his couch for spare dimes to ensure he can afford to return is San Franciscan Wade Boyd. Forty-plus with long vermilion hair, Boyd has been racing at the TT for 10 years,

coming back on a shoestring to try to beat his personal best.

“It’s totally amazing whatever speed you’re doing,” he says in the midst of

preparing a Kawasaki ZX-9R he rescued from a salvage yard. “Riding down Bray Hill is like diving off the edge of the world at 160 mph! It’s totally ex->

treme. There’s no room for error here. We normally lose someone-I call them a friend or relative whether I knew them or not-every year. Nobody wants to go home in a box, so you’ve got to keep it safe and sane.”

There are reminders of how unforgiving “real” roadracing can be everywhere during the TT fortnight (one week for practice, one for racing). The crowd is full of Joey T-shirts, pins and replica Arai helmets. And there were racers who paid the ultimate price this year. When tragedies happen, the old arguments for ending the TT begin anew.

One question is continually fired at supporters: How relevant is the TT? The festival is regularly referred to as an anachronism, a throwback to another time, and when you hear that the races are timed on stopwatches (by humans, for crying out loud!) and that they experimented with transponders for the first time this year, you might agree. But consider this: No one has to race here-there are no binding contracts, no championship points. Men and women choose to race here because they love the place.

Also, Honda has never lost its appetite for the TT, and because of that, other manufacturers have felt obligated to support British-based satellite teams to combat the biggest of bike companies. Because of this, the island is home to the most grueling and, some would say, important production races on earth.

Hugely popular bikes in both the 1000 and 600cc classes are given the ultimate test on the toughest racetrack this planet offers. Minimal changes (suspension, tires, exhaust, fuel) barely change the character of the bikes any of us can buy. Yet these machines are coping with a circuit, conditions and speeds that have to be witnessed to be believed. After TT week, riders roll onto the ferry home knowing that any bike that covers itself in glory on the Mountain circuit is one hell of a streetbike. If that doesn’t make the TT totally relevant to modern sportbikers, then I don’t know what does. Long live the TT! -Gary Inman

King Kenny’s V-Five four-stroke

If imitation is the sincerest form of it, then Kenny Roberts is set to flatter his old rivals Honda. Starting next year, there will be two different types of VFive on the starting grids for the new four-stroke MotoGP series. And one will be a Proton KR5. >

Roberts finally confirmed at the Spanish Grand Prix at Catalunya growing rumors that he was to build a V-Five, pre-empting his own planned launch with his own obvious excitement at the prospect. And he wasn’t just imitating Honda, he insisted, though clearly the out-of-the-box success of Big Red’s V-Five RC21IV had been influential.

The biggest reason had been his own V-Three two-stroke, launched as the Modenas in 1997, now running under the Proton name. After a rocky start, the little 500 has developed into a fine machine, not only beautifully designed, made and finished, all in-house at Roberts’s ever-growing factory headquarters in Banbury, England, but also incorporating cutting-edge chassis technology and aerodynamics.

It remains unsuccessful. He dreamed of undermining the class-ruling fourcylinder 500s by exploiting a lower>

weight limit, giving away ultimate top speed in exchange for better braking, handling and corner speed. The dream didn’t work.

“We’ve spent a lot of money with weight saving-lightness is cost. I don’t want to be penalized any more by being slower on the straight,” he said.

Roberts had steadily increased the size of the staff at his GP Motorsports establishment in the heart of England’s so-called “Formula One Belt” over the past 12 or 18 months, with a number of former F-l car engineers, and admitted

he had been tempted by the notion of a lightweight three-cylinder 990cc fourstroke, like Aprilia’s Cosworth-developed “Cube.” This not only has a lower weight limit than that applied to four/five-cylinder designs (298 pounds vs. 320) but would also benefit from a big body of F-l technology, having cylinders almost the same size as the three-liter V-10 engines that are universal in the top car class.

The four-stroke knowledge was not, however, confined to 330cc cylinders he said. “Two-stroke engines are a black art-nobody really understands how they work. With four-strokes, there’s a huge body of knowledge available, just down the road.”

They had decided to go with a fivecylinder design during pre-season tests, when nobody had yet seen the Honda, but everybody knew it had been setting impressive test times.

The new bike will be called a Proton, >

like the current KR3 Triple. And like the Honda it will have two cylinders in the rear upper bank, and three pointing forward. Roberts would not reveal the angle of the vee, but it is likely to be 72 degrees like the Honda, a fifth of 360 degrees, for balance reasons. Firing intervals were not yet decided.

Drawings had been completed and components were already being made, said Roberts. As before, they have the benefit of the Proton car factory’s rapid prototyping facilities; while a new wide-line chassis raced for the first time at Catalunya already has the frame tubes splayed out to accommodate the new engine.

A resin mock-up of the powerplant should be ready by the end of July, with a motor running by the end of November, and testing starting directly thereafter, said Roberts. “I’ll be doing some of the riding myself,” he said.

“We know how to make a motorcycle go around corners now,” he said. “If we can make one that can go fast down the straight as well, then we should be competitive.” -Michael Scott

Lino Tonti, 1920-2002

One year ago, the motorcycling fraternity mourned the loss of the great “Doctor T,” Ducati’s Ingegnere Fabio Taglioni. Now, it gathers again to remember another visionary from the Italian motorcycle industry, Lino Tonti.

Born in 1920 in Cattolica, a small town near where the Misano race circuit now stands, Tonti got his first job

at Benelli. There, he quickly proved his talent and was given the opportunity to work on some very advanced machinery, such as a supercharged Four that was being developed for roadracing. After WWII, Tonti moved

to Varese to join Aermacchi (later to become Harley-Davidson’s lightweight division and then Cagiva), which had acquired the rights to build a 125cc scooter he designed with then totally innovative (and now very popular) 16-inch wheels. In 1957, Count Giuseppe Boselli, founder of Mondial, entrusted Tonti with creating a twin-cylinder 250cc Grand Prix racer to replace the world-conquering Mondial 250 Single.

At the end of that same season, however, Mondial-together with Güera and Moto Guzzi-withdrew from racing. Even so, the development work for the new Twin did not go to waste. Tonti drew from that experience to design twin-cylinder roadracers such as the Pattoni 350, Paton (PAttoni-TONti) 500 and, in 1958, the Bianchi, which progressed from 250cc to 350cc in the hands of Remo Venturi and, ultimately, to the 454cc limit for the 500cc class. When Bianchi quit the motorcycle business, Tonti was hired by Güera, but those were hard days, and the two-year association produced few results.

In 1967, Tonti started what is regarded as the most productive period of his professional life, when he joined Moto Guzzi. The company had not yet been scooped up by DeTomaso, and the spirit was still there. From the moderate-performing V7 750, Tonti devel-

oped one of the most fascinating sportbikes of the time: the V7 Sport. When worker strikes prevented Tonti from getting his developmental work done, he did it himself, physically fabricating what would become one of the most celebrated frames of the time: the red-

painted, chromoly-tube unit that is still used on today’s California models. But while that was a good time for Tonti, it also was bad, because he had an unfortunate accident while testing a V7 Sport. The drum brakes he wanted to retain in the face of the already superior new disc brakes backfired on him, and his right leg was in a cast for a couple of months, leaving him with a permanent limp.

While working hard to give Guzzi its first sportbike in years, Tonti somehow found time to give life to his most successful racer: the Linto 500. The engine was the result of marrying two Aermacchi 250cc (Harley Sprint) horizontal Singles, and the frame was a fine work of competent engineering.

Tonti remained with Moto Guzzi until he retired in the mid-’80s, but he was often seen at the Mandello del Lario factory well into the 1990s. He will be missed. -Bruno de Prato

Bobby Strahlmann, 1921-2002

Bobby Strahlmann, for many years Champion Spark Plug Company’s technician at national motorcycle races, died recently in Ocala, Florida, aged 81.

Many, including myself, have benefited from his insights into engine performance, and his humor in the racing situation. In truth, Strahlmann was much more than a technician, for his engine experience both at trackside and in

the dyno room gave him unique insight into what could be learned from looking at sparkplugs.

The usual sparkplug representative’s job is to keep you from having a bad day with his company’s product, but Strahlmann went beyond that. If he saw that you had basic engine variables under control, he would help you work in closer to the limit, to get all

your engine could give. After examining your plugs under a magnifying glass, he would say something real and useful like, “You can push the timing up a half, maybe a whole degree.” We appreciated this because it worked, and because he explained what he saw and how he interpreted it. We always learned something useful from him. And he was generous with product to those who could make good use of it.

After his retirement from Champion, Strahlmann was involved in the construction of replica WWI combat aircraft. He is survived by his wife of 56 years, Lorraine. -Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue