Clipboard

The racers went in Twin by Twin

ALL GOOD THINGS, IT APPEARS, COME IN twos. Certainly, duality was the overriding theme of the first official World Superbike off-season test, held at Phillip Island in Australia during early February.

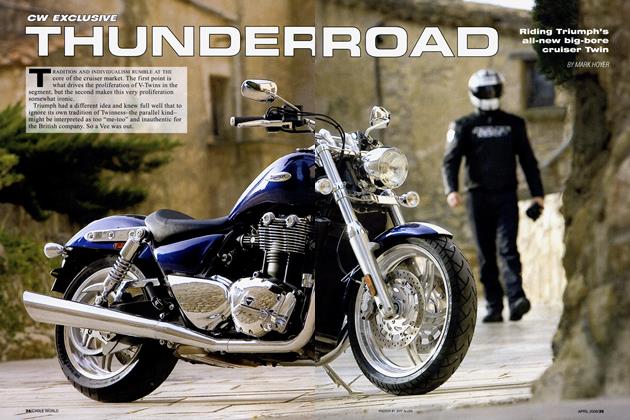

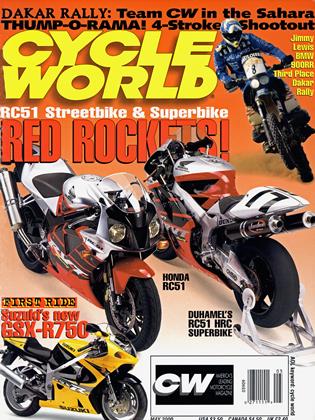

First (and finally), Honda wheeled out its RC51 twin-cylinder works bike. Its mere presence caused frissons to no end along pit lane, and the effect was only heightened when Big Red’s big Twin finished the three-day test at the top of the lap-time chart. Shinichi Itoh-a past Suzuka 8-Hour winner and All-Japan Championship regular-was fastest, with World Superbike contender Colin Edwards just a fraction behind (see “World Superbike Weapon,” page 52).

Honda wasn’t the only manufacturer to stir things up, however. On the

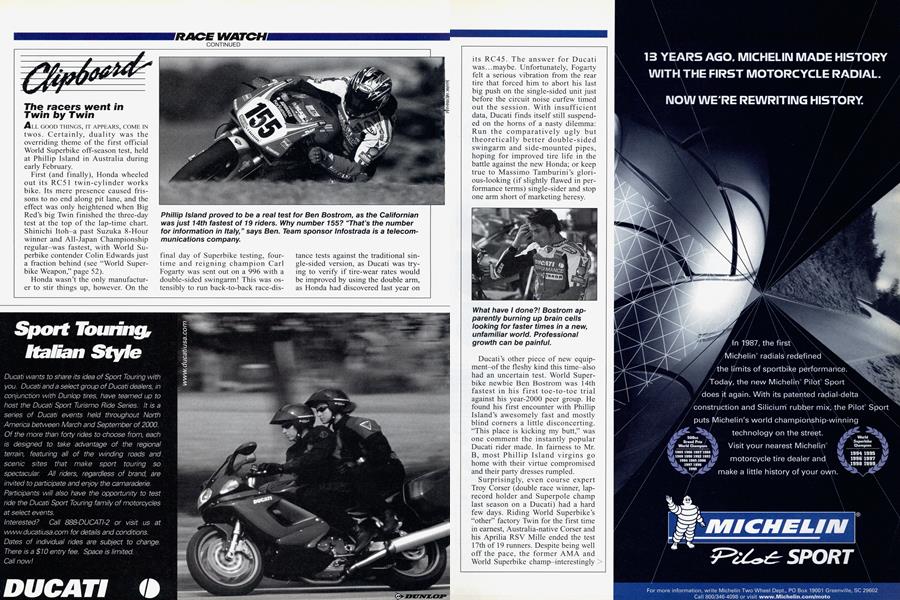

final day of Superbike testing, fourtime and reigning champion Carl Fogarty was sent out on a 996 with a double-sided swingarm! This was ostensibly to run back-to-back race-dis-

tance tests against the traditional single-sided version, as Ducati was trying to verify if tire-wear rates would be improved by using the double arm, as Honda had discovered last year on

its RC45. The answer for Ducati was...maybe. Unfortunately, Fogarty felt a serious vibration from the rear tire that forced him to abort his last big push on the single-sided unit just before the circuit noise curfew timed out the session. With insufficient data, Ducati finds itself still suspended on the horns of a nasty dilemma: Run the comparatively ugly but theoretically better double-sided swingarm and side-mounted pipes, hoping for improved tire life in the battle against the new Honda; or keep true to Massimo Tamburini’s glorious-looking (if slightly flawed in performance terms) single-sider and stop one arm short of marketing heresy.

Ducati’s other piece of new equipment-of the fleshy kind this time-also had an uncertain test. World Superbike newbie Ben Bostrom was 14th fastest in his first toe-to-toe trial against his year-2000 peer group. He found his first encounter with Phillip Island’s awesomely fast and mostly blind corners a little disconcerting. “This place is kicking my butt,” was one comment the instantly popular Ducati rider made. In fairness to Mr.

B, most Phillip Island virgins go home with their virtue compromised and their party dresses rumpled.

Surprisingly, even course expert Troy Corser (double race winner, laprecord holder and Superpole champ last season on a Ducati) had a hard few days. Riding World Superbike’s “other” factory Twin for the first time in earnest, Australia-native Corser and his Aprilia RSV Mille ended the test 17th of 19 runners. Despite being well off the pace, the former AMA and World Superbike champ-interestingly >

dropped last year by Ducati after finishing third in the championship-remained upbeat about his forced arrival in the Aprilia’s saddle. “I think the engine is good and the chassis is not too bad,” said Corser, who suffered a viral illness on the second day of testing that limited his track time. “Our goal will be to finish top IO in the first races, but I’m confident we can get podiums by the end of the year.” Aprilia stayed on for more testing, and lap times improved, as did Corser’s feelings about the bike’s potential.

For the other factory teams, Phillip Island was a mixed bag of fortune cookies, with Suzuki and PierFrancesco Chili coming out best of the four-cylinder entries. Third fastest on the strength of his absolute final lap, Chili was riding an updated but still 1999-spec GSX-R750 (as in the U.S., the factory has decided to wait another

year before racing the 2000 version).

Fourth fastest was Fogarty, who is much more the great racer than great tester. Spaniard Gregorio Lavilla was a surprising fifth, carrying the green flag for his Kawasaki teammate Akira Yanagawa, who crashed and suffered an ankle injury on the first day.

A whole squall of All-Japan Championship contenders politely crashed the tests. Aside from fast-man Itoh and his RC5l, most filled the bottom of the time charts, save Kawasaki’s Hitoyasu Izutsu. No slouch, the speedy Japanese rider ended up sixth fastest and put himself just ahead of Hondamounted Aaron Slight.

A minor shock was the sight of Vittoriano Guareschi’s name above that of his ostensibly more illustrious (and much slimmed-down) Yamaha quasiteammate, Noriyuki Haga. Contrary to Haga, who gets full factory support, the Italian is no longer a full-on works man. He now rides for the Belgarda Yamaha team, which formerly handled the factory’s official effort. As a consequence, Guareschi is riding a YZFR7 that uses a ’99 factory chassis fitted with a non-factory engine. Based on Phillip Island’s showings, his second full year on the World Superbike circuit could be a lot more fruit>

ful than his first, and his performance raised a few eyebrows in the paddock.

In the end, Itoh-and, more importantly, long-tenured World Superbike regulars Edwards and Slight-proved at Phillip Island that Honda may have the right stuff to take a Superbike title in the RC51’s debut year. But you can

count on Ducati’s race-win superconductor, “King Carl” Fogarty, having something to say about that. The last word, however, goes to Chili, who summed things up so far: “Honda has built a very fast bike, and I think everyone will want to ride it next year.” Gordon Ritchie

The-moto underground

THERE’S A HARD-CORE RUMBLING IN the underground of the motocross world. It’s coming from a place where a haze of blue-white smoke hangs in the air, roost flies in your face and the racers are so close you can see the whites of their eyes as they pancake their 125s and 250s flying on by.

It’s the PACE-promoted National Arenacross Series, an intense, highenergy show, the motorsports equivalent of a punk concert in a small club. But instead of some screaming halfwit with a Mohawk spitting at you, you’ve got talented racers banging bars, chucking roost and skying double jumps. The venues are more intimate and the action is closer and harder-hitting than any other form of motocross racing. Average lap time? Just 30 seconds. Makes the 1-minuteper-lap pace of your average Supercross seem glacial by comparison.

It’s been described as part slamdance, part hockey hip-check and part roller derby, except all on motor>

cycles, so it’s way cooler-and there’s a jump contest, too!

In all, the Arenacross world is a strange one. If you don’t already know about it, you probably aren’t one of the thousands of fans getting a winter fix at venues with names such as the Cow Palace, Lazy E Arena and the Livestock Events Center. Don’t misunderstand, the series has moved up-market from its more humble beginnings so it now also visits places like the fairly large ARCO arena in Sacramento. But in general terms the series goes where Supercross does not, particularly through the snowbelt to give more remote motoheads something to get them through the cold, roostless winter.

Packed into small arenas, the tracks generally are very tight, and often have only four straightaways. “It’s weird. When you’re racing, the track doesn’t seem that small,” says series star Denny Stephenson, who’s been competing in AX four years now. “But sometimes when I walk the track before the races, I can’t believe how small it really is. I’ve gone back to do some Supercrosses and can’t believe how much space there is. I think that’s one of the reasons the

guys in Supercross are generally more cordial. In Arenacross, when you get an opportunity to pass, you see that door open a crack, sometimes you’ve got to kick it open! You might not get another chance.”

While there is extensive TV cover-

age on Speedvision and Fox Sports Net, those who have seen an Arenacross in person generally agree that the racing loses a lot in the boob-tube translation. Like with hockey, the action is better live. “What doesn’t show up on TV is how tight and furious the racing is,” says Steve Dye, manager of the Arenacross series. “You don’t have any idea how crazy it can get.”

Whereas in Supercross the sheer scale of the venues means that most fans, even those seated near the floor, are quite removed from the action, Arenacross is right in front of you-there are usually 8000 to 18,000 seats at most rounds, so it’s hard to be too far away. When the pack comes around, you’re as likely to hear your fellow spectators yelling, “Go, Denny!” as, “Cover your beer!” to remind you that you might need to keep the roost out of it. “The crowd is super-close, really part of the action,” says one jaded photojournalist who’s been shooting all kinds of motorsports for years. “In a lot of ways the

racing is better than in Supercross, too. They really bang bars and are aggressive. It’s kind of how Supercross used to be.”

Three-time Supercross Champion Rick Johnson, on hand for TV commentary said at one of the events, “Supercross has gotten a little more cordial in the ’90s and now in 2000, but these Arenacross guys race hard. It’s in real tight quarters, short races, so there’s going to be contact.”

Contact, indeed. Says Stephenson matter-of-factly, “When you go into a fight you know you are going to get hit. Sometimes you have to make

things happen.” He added that although there is a lot of latitude on the track, it isn’t a complete free-for-all. It can’t be-you see too much of the other racers. “There are 72 main events this year. We’re a tight-knit family on and off the track, but we’re pretty open to doing what you want as long as you aren’t hurting anybody.” And as PACE Director of Communications Lance Bryson pointed out, there is a bit of a get-what-you-give code: “These guys remember if they’ve been unfairly taken out. Let’s just say they keep score.”

Arenacross star Buddy Antunez has three consecutive titles to his credit, and as the 1999-2000 series swung through midseason he was again leading the points and looking good for his fourth championship. But Suzuki teammate Stephenson might have something to say about that. “I’ve really put a lot more effort into it this year, training and stuff,” Stephenson says. “Before, I was just coming out and enjoying the racing, but I’m a lot more serious now. Buddy’s got a good lead. He’s pulled away a little bit in the points. But when you race four mains a weekend, things can change really fast.”

Therein lies the beauty.

Mark Hoyer

PACE joins the race

BACK IN THE OLD FEUDAL DAYS, IF you roadraced with any club but the AMA, you were an “outlaw.” The AMA would send its officials to other clubs’ events to take riders’

names. These riders-even if entered under the usual false names like Dick Tater or Sumner Tunnel-would then be suspended. After some murky legal pushings-and-shovings, this predatory behavior was replaced by an uneasy peace between the AMA and “the clubs”-regional roadracing organizations such as California’s AFM, the East Coast’s AAMRR, and the Southeast’s ERA/WERA.

Clubs developed fresh expertise in running races because they did it so often, with many classes. Because the same officials appeared at all the races in a series, race operations and cornerworking advanced to a high standard.

In the AMA, volunteer race workers were used because AMA roadraces took place all over the country. And because different people worked the various events, they were prevented from developing much professionalism-or sympathy for the riders. Such race workers were, too often, older men with “a whistle, a belly and an attitude.”

When AMA starting grids shrank alarmingly in the late 1970s, its management realized it had to reach an accommodation with the vigorous regional clubs, whose memberships were always increasing. The AMA needed a grass-roots organization, a farm league to supply riders, and it needed experienced race management and event workers. The clubs needed the clout of a larger organization, and they needed improved access to

insurance. Roger Edmondson’s Championship Cup Series became associated with the AMA in an evolving symbiotic relationship.

After some years of relative tranquility, that relationship exploded in the early ’90s. The AMA picked up most of the pieces and Edmondson went his own way with CCS and, later, with the NASB and Formula USA.

Now, after winning a noisy lawsuit against the AMA, Edmondson and associates have sold CCS to PACE Motor Sports, which also purchased Doug Gonda’s foundering Formula USA national series. What will happen now?

PACE is well known for its successful Supercross/Arenacross promotions, but roadracing is a new thing for them. PACE is a business, which is what you have to be to compete in a world of other businesses. Business means lean operation, aggressive marketing and strictly rational decision-making. Gary Becker, PACE’s CEO, has said, “We’re an entertainment-promotion company,” and the new roadracing series will be “an entertainment property based around motorcycle racing.”

Some months ago, I speculated quite innocently in these pages as to what might happen if some businesslike entity were to “pick up” U.S. motorcycle roadracing, just as Bernie Ecclestone picked up Formula One auto racing. With skillful application of business methods in place of tradi-

tional management, F-l racing has become very popular, profitable and a highly valued TV commodity. Could PACE do something like this with U.S. motorcycle racing?

We don’t know, but obviously PACE thinks it’s worth a try. Its new national series features four horsepower-limited or “spec” classes like those formerly run by Edmondson, with events scheduled to avoid conflict with the AMA Superbike Championship. The clear message is, “We don’t want to fight, but we do plan to play.” I see PACE’s interest as a test. Can they make money with this? Can this kind of racing be successfully promoted, and sold to TV and to sponsors? Further, PACE recently announced its acquisition of a number of high-profile dirt-track events formerly promoted by Chris Agajanian, including the Sacramento and Del Mar Miles. No schedule has been announced, but the events will be sanctioned by Formula USA.

What does this mean for the AMA? The AMA has for years oscillated between an outgoing determination to make racing a successful business, and a traditional inward-looking desire to build up the club and serve racing’s inner circle. It has a good, competitive series now, with strong factory and sponsor participation, but the wider audience that may or may not exist for this exciting sport has so >

far been elusive. Competition from the businesslike PACE can only serve as a stimulus to the AMA to become more businesslike, and that’s good. The greater racing’s financial strength becomes, the more likely it is still to be here next year.

Asked about the new development, Edmondson replied, “They’re going to do what I wanted to do.”

In an early internal PACE discussion of the new roadracing property, someone asked, “But will it sell tickets?” Lance Bryson, director of communications for PACE, replied, “I don’t think anyone has tried in America.”

PACE will try. That has to be a good thing for the sport.

Kevin Cameron

Jimmy Button injured

“IT’S ALL LUCK,” SAID JEFF EMIG, SPORTing a pair of broken wrists from a recent crash. “It’s all luck whether a racer gets hurt or not.”

It was a Saturday afternoon and Team Yamaha’s Jimmy Button lay motionless in the whoop section of San Diego’s Qualcomm Stadium Supercross course.

A small, concerned crowd, Emig among them, had gathered around the fallen rider trying to do anything they could to help-and hoping Button would get up on his own. He didn’t, and wouldn’t, for weeks.

During a 250cc practice session, Button took a low-speed tumble before the first lap had even been completed. He hit the ground head-first and suffered then-unknown neck and spinal injuries. He was taken to a neighboring hospital whereupon it was learned that he had suffered a bruised spine, stretched ligaments and trauma-induced paralysis. Thankfully, doctors explained the Yamaha rider would not suffer permanent paralysis, but his recovery would likely be very slow and difficult.

His condition later improved, and the 26-year-old was transferred to a hospital near his parents’ home in Phoenix, where he began a strenuous rehabilitation program. As anticipated, feeling and movement came back to Button slowly, but each small improvement brought hope and encouragement. By press time, he was able to move his arms and legs, and for a few minutes at a time, stand on his own.

In a grand gesture of support, Chaparral Motorsports in San Bernardino, California-once a sponsor of>

Button’s-held an auction to help generate proceeds for the fallen rider. Showing true compassion and concern for the 1999 Washougal National winner, the motorcycle and entertainment industries cleaned out closets and trophy rooms, donating upward of 400 items, all of which were auctioned off at Chaparral and over the Internet.

As one would expect, there were many items donated by members of the two-wheeled world. Contributors included Jeremy McGrath (his chrome helmet worn at the second Anaheim round drew $9750!), Emig, Bostrom brothers Ben and Eric, Kurtis Roberts, Mat Mladin and Travis Pas-

trana. But several notable outside-theindustry-types participated as well, with actors Jeremy London (“Party of Five”) and Matt LeBlanc (“Friends”), not to mention former Formula 1 World Champion Jacques Villeneuve-a certified moto-nut-stepping in to help. In the end, more than $65,000 was raised for Button, who has already begun talking about climbing back aboard a motocross bike. A concrete prognosis wasn’t offered by his physicians, though the wide-ranging support from his fans and the industry, along with his early steps toward recovery, have his spirits high.

Eric Johnson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontFree Bikes And Other Myths

May 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOpening the Eastern Gate

May 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCWorking All Night

May 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

May 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupTop Tourer? Honda Gl1800 Gold Wing

May 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Street-Traciker

May 2000 By Nick Ienatsch