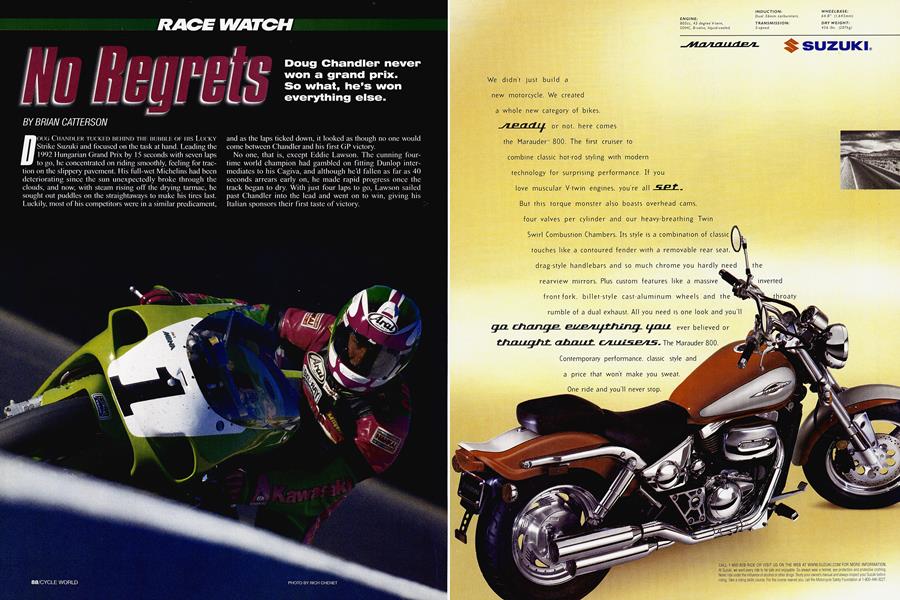

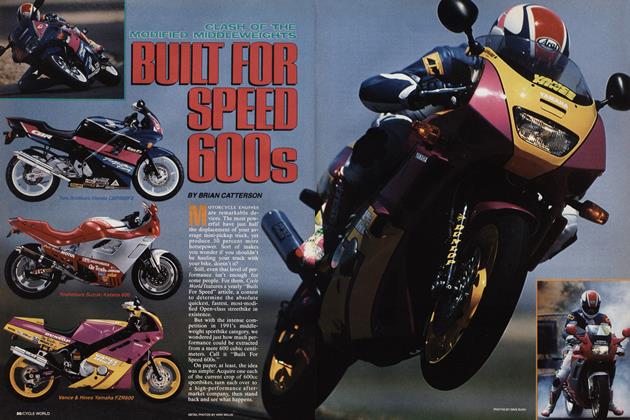

No Regrets

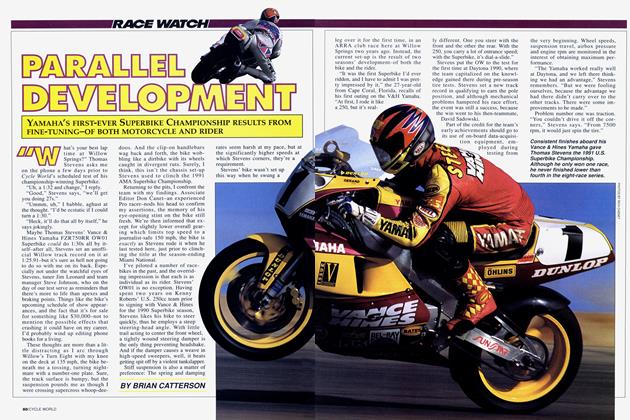

RACE WATCH

Doug Chandler never won a grand prix. So what, he's won everything else.

BRIAN CATTERSON

DOUG CHANDLER TUCKED BEHIND THE BUBBLE OF HIS LUCKY Strike Suzuki and focused on the task at hand. Leading the 1992 Hungarian Grand Prix by 15 seconds with seven laps to go, he concentrated on riding smoothly, feeling for traction on the slippery pavement. His full-wet Michelins had been deteriorating since the sun unexpectedly broke through the clouds, and now, with steam rising off the drying tarmac, he sought out puddles on the straightaways to make his tires last. Luckily, most of his competitors were in a similar predicament,

and as the laps ticked down, it looked as though no one would come between Chandler and his first (iP victory. No one, that is, except Eddie Lawson. The cunning ftur time world champion had gambled on fitting Dunlop inter mediates to his Cagiva, and although he'd fallen as far as 40 seconds arrears early on, he made rapid progress OflCC the track began to dry. With just four laps to go, Lawson sailed past Chandler into the lead and went on to win, giving his Italian sponsors their first taste of victory.

Unfortunately for Chandler, that’s as close as he ever came to winning a GP. In a four-year international career that saw him ride for Yamaha, Suzuki and Cagiva, he notched his share of pole positions and podium finishes, but he never quite managed to mount the top step. And when Cagiva pulled the plug on its 500cc effort at the end of the 1994 season, the GP career of America’s brightest hope was quietly extinguished.

But that’s all in the past for Chandler, and he harbors no ill will. At age 31, he’s been racing for a mind-boggling 25 years, and he regards this as just another episode in a lifetime of ups and downs.

“I enjoyed my time over there,” Chandler says today. “I felt I was a little short-changed, because I didn’t think we were finished over there, but that’s the way it happened. When I left Suzuki to go to Cagiva, I was offered a lot of money. I knew there was the potential of not doing good on the bike, but you can’t pass up a deal like that. But I can’t help feeling that if maybe I’d stayed at Suzuki, I’d still be there today.”

Born September 27, 1965, to parents John and Sharon, Chandler started racing at the tender age of 6, riding a Honda 50 Mini-Trail at short-tracks near his Salinas, California, home. He quickly graduated to 80s, and then to 250s, racing three to four times a week through his teens. Upon graduating high school in 1983, Chandler jumped in his van and drove to Illinois, where he won the very first Pro race he entered, the Santa Fe Short-Track. At age 17, he became the second-youngest rider ever to win a National. (Scotty Parker was one month younger when he won his first in 1981.)

Chandler finished third the following weekend at the DuQuoin Mile, was crowned AMA Rookie of the Year at season’s end, and promptly signed a fat contract with Honda. Along the way, he’d begun dating a race promoter’s daughter, and in due course, he and Sherry were married. The only thing missing from the fairy tale was a happy ending.

That would have to wait, because after just one year as a factory rider, Chandler was left without a ride when Honda decided to downsize its dirt> track effort. But the year hadn’t been a total loss: In addition to notching his second career win (at the Ascot TT), he’d also gotten his first taste of roadracing. And he liked it.

“Back then, with the Camel Pro Series, you could get extra points by roadracing, so Honda gave me a Formula One bike,” he recalls. “I didn’t know what I was doing, I was just kinda riding around.”

The following year, Chandler joined forces with Freddie Spencer and SuperTrapp, an arrangement that would last four years. Racing privateer Hondas, he notched another two TT wins at Santa Fe, plus victories in the Ascot Half-Mile and San Jose Mile. On the asphalt, he raced an RS500 GP bike in the F-l class, before making the switch to a VFR750 Superbike when the rules changed for 1987.

Chandler earned a roadrace podium finish with a third place in that season’s finale at Sears Point. The following year, he fared even better, earning the nickname “Mr. Third Place” en route to third overall for the season.

It was then that Chandler decided to get serious about roadracing. Weighing his options, he decided to re-prioritize, putting his beloved dirt-track on the backburner.

“I had my own say in that,” he says. “I didn’t see a future in dirt-track. The AMA kinda hosed Honda by making them run restrictor plates, and it got to the point where there was only one manufacturer involved. If Harley’s the only one racing, why should they spend any money?

“It’s pathetic, because nothing compares to a good mile. It’s the closest form of racing. When you can go from third to first to fifth in half a lap, that’s cool. You have some races like that on the road bikes, but you don’t have as many guys.”

For 1989, Chandler signed to ride the fledgling Muzzy Kawasaki Superbike. It was a frustrating season. “We broke at every race except the last two at Mid-Ohio and Topeka, where we > won,” he recalls.

Though 1989 was frustrating, it did bear fruit. In winning his first Superbike race, Chandler became one of just four riders to complete an AMA “grand slam,” with wins in every racing discipline run on the Camel Pro Series: mile, half-mile, short-track, TT and roadracing. And he had one last hurrah in the dirt, with a victory at the Ascot Half-Mile.

Chandler built on that success the following season, winning four of eight roadraces to become the 1990 AMA Superbike Champion, and scoring victories in the World Superbike rounds at Brainerd, Minnesota, and Sugo, Japan. The years of hard work had finally paid off.

Then, following in the tire tracks of former Superbike champs Eddie Lawson, Wayne Rainey and Bubba Shobert, Chandler opted not to defend his title. Muzzy wanted him to go World Superbike racing full-time, but the lure of the GPs was too much, and Chandler signed to ride on Kenny Roberts’ Yamaha farm team.

“Anybody is going to make that same decision,” Chandler insists. “Ultimately, 500s are the top class. Salary-wise, it’s not a lot different from Superbikes, but if you tell your helmet and leathers companies that you’re racing 500 GPs, you can double what you’d normally get from them.”

The 1991 season saw Chandler learning the GP ropes, finding his way around unfamiliar circuits and, more than anything, marveling at teammate Wayne Rainey.

“Wayne was the best by far,” he says.

“I don’t think ability-wise, or talentwise, he was the best; it wasn’t easy for > him, like it was for Kevin Schwantz. Wayne would just work and work and work to make it. He had so much determination. I remember when I was there in ’91, Wayne would still be a second off in Sunday-morning warmup. They’d completely disassemble that thing, change the offset, the rake, the pivot or the engine position or something, and he’d wheel it out there and race it, and race up front!”

Seeing first-hand how Rainey and Yamaha worked, Chandler expected to find more of the same when he joined Schwantz at Suzuki for the ’92 season. But although he has high praise for the team, he found Schwantz’s

technical knowledge sorely lacking, “After being around Wayne in ’91, I was looking forward to working with Kevin,” Chandler says. “That’s when I figured out why he was in the position he was in, all broken up. No matter what the bike was like, he’d just throw his leg over it and pin it!”

The following season, Chandler jumped ship again, with Cagiva becoming his third new home in as many years. He spent a bittersweet two seasons there, plagued by mechanical problems and injury.

“The throttle stuck,” Chandler says of the biggest get-off of his career, in Malaysia. “You go down the back straight, then there’s a fast right, a left, and then another long right. I went in there, and when I went to roll off, it just kept going. I broke all the bones in the top of my left hand, and punctured the palm. My glove was all bloody.”

Despite the fact that Chandler didn’t miss a race, Cagiva took the opportunity to hire John Kocinski mid-season, after his falling-out with Suzuki’s 250cc GP team. This chafed Chandler.

“They brought in Johnny, which I think was a slap in the face to me. When a team does something like that, you feel you’re not getting 100 percent support. Having the team behind you gives you more incentive to go out there and do a better job for them. When you start having doubts about them, you’re not gonna risk your neck for them.”

Matters improved somewhat in 1994, when Cagiva hired former Roberts/Lawson mentor Kel Carruthers to tune for Chandler.

“Kel helped me a lot,” Chandler says. “He got me going again as far as my racing. I wasn’t so much doing it for Cagiva as for us. I think we kinda pulled the team through that year and made the bike what it ended up being, which was damn close to being a really good bike.”

Then came the paralyzing injuries suffered by Chandler’s good friend Rainey.

“That was a big one,” Chandler says glumly. “That just didn’t seem real. We were all supposed to be on the same plane that night to come home, and I expected Kenny to walk through the door anytime and say Wayne was okay. But it never happened.”

In tribute to Rainey, two of the Chandlers’ three children-Jett Wayne, 6, and Rainee, 2-are named after his former teammate.

Reeling from the shock of Rainey’s injuries and unexpectedly left without a GP ride after Cagiva’s withdrawal, Chandler landed on his feet in a most unexpected place: back in the AMA Superbike series, aboard a factory Harley-Davidson VR1000. Had things changed much during his absence?

“The biggest difference was the manufacturers got involved,” Chandler says. “When I left, it was just Kawasaki and Suzuki. When I came back, we had all the majors involved, even Harley. The money’s good enough that you can stay home and still make a pretty good living.”

Unfortunately, Chandler’s year aboard the Harley was plagued by injury, rattling his confidence.

“I took myself out of the first half of the year,” he says. “At Daytona I fell and broke my collarbone, and > then I fell and rebroke it testing at Laguna. It’s bad because you start really doubting yourself. You think you know what you’re doing, and then you keep falling off.”

“It’s not worth the risk anymore,” Chandler says. But that doesn’t stop him from training on dirt-track bikes, which he insists are the best tool for up-and-coming roadracers.

“It gets you used to the speed, and having the bike moving around underneath you. You learn a lot more about chassis set-up, too; it relates more to the roadrace stuff.”

After his disappointing season with Harley, Chandler re-upped with Muzzy Kawasaki for 1996, returning to the team with whom he won the 1990 title. And the outcome was the same: Chandler clinched the numberone plate with a dramatic victory in the barn-burning, winner-take-all finale in Las Vegas.

“It was pretty enjoyable, after several frustrating years,” Chandler says of his season-long rivalry with Honda’s Miguel Duhamel. As for this coming season, well, that looks to be even more competitive.

“Everyone makes it out to be just Miguel and me, but you’ve got Mat Mladin on the Ducati and Aaron Yates coming up on the Suzuki. It’s good to have those new guys, because we’re all going to be better riders in the end.”

Asked if there are any races he’d like to win that he hasn’t, Chandler doesn’t name the Daytona 200 or the Suzuka 8Hour. Instead, he cites the World Superbike round at Laguna Seca.

“I’m looking forward to it this year. I thought we had a good chance last year, but we got kinda hosed by brake problems. When we tested at Laguna recently, my lap times were quicker than what Anthony Gobert did last year in the race, so I’m feeling pretty confident.”

At an age when many riders are

contemplating retirement, Chandler is still going strong. How long will he keep it up, and what does he envision for the future?

“If I can do this until I’m 35, that’ll be pretty good. After that, who knows? Car racing looked pretty good, but when Eddie Lawson started driving Indy Lights, I went to Laguna and got the inside info on how all that works, and I got disgusted. It’s so political.

“I’ll probably stay involved in the sport. I don’t know if I’d rather run a team, or just open up a bike shop here in Salinas.”

Somehow, the latter scenario seems appropriate for the down-home dirttracker done good. Because in spite of his fancy Rolex watch, Chandler’s a regular Joe. He prefers musclecars and pickup trucks to sports cars, eats hamburgers instead of rabbit food, and chews tobacco. True, he lives in the upscale part of his hometown, but then Salinas isn’t exactly the Monterey Peninsula. He’s the guy next door, who just happens to be one of the most accomplished motorcycle racers in history.

“You’d always like to win everything, but you’ve got to accept what, you’ve got and be happy with it,” Chandler says in summary. “You can’t mope or complain about it. It’d have been nice to win a GP or a world title, but I’ve done pretty good without doing those things.”

Who’s to say otherwise? □