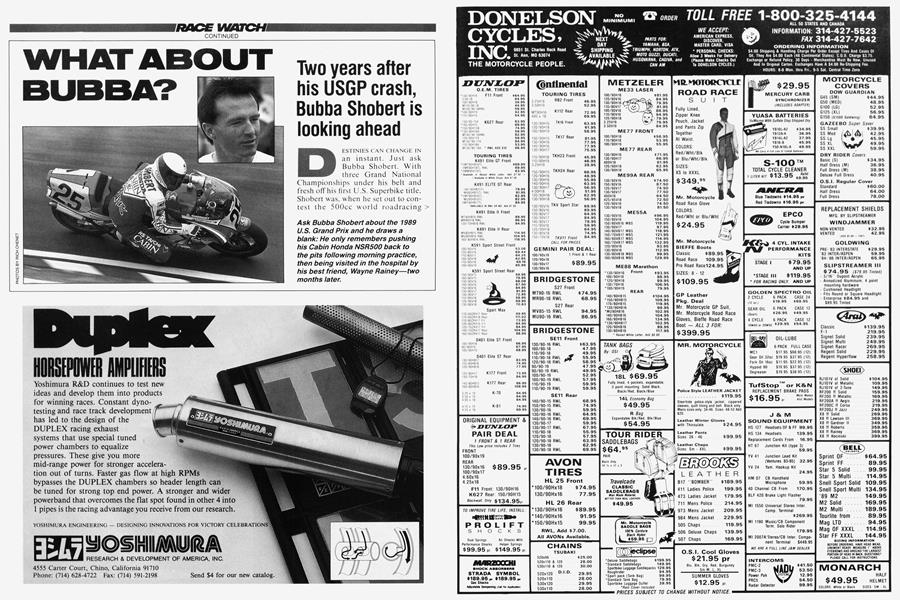

WHAT ABOUT BUBBA?

RACE WATCH

Two years after his USGP crash, Bubba Shobert is looking ahead

DESTINIES CAN CHANGE IN an instant. Just ask Bubba Shobert. With three Grand National Championships under his belt and fresh off his first U.S. Superbike title, Shobert was, when he set out to contest the 500cc world roadracing championship in 1989. on his way to greater racing glory. But his debut GP season lasted just three races—one of which he doesn't even remember.

Roadracing fans are familiar with the story of Shobert’s accident. Circulating on the cool-off lap of the 1 989 USGP at Laguna Seca, Shobert was congratulating third-place-finisher Eddie Lawson when the duo came upon Kevin Magee, who had stopped on the racetrack to vent his frustrations in a smoky burnout. Lawson looked ahead just in time to avoid a collision, but Shobert rearended Magee, knocking himself unconscious and breaking the Australian's lower leg and ankle.

Shobert was airlifted to San Jose Medical Center, where he remained in a coma for seven days. When he came to, he was not the same person as before, having difficulty with even the simplest tasks. He was flown to a rehabilitation center near his parents’ home in Texas, where he eventually improved to the point that he began talking about returning to racing.

Two years later, however, Shobert doesn't talk much about racing, as we discovered when we caught up with him recently at his home in Carmel Valley, California.

Yes, he admits he has ridden a Yamaha TZ250 during a Team Roberts test session at Laguna Seca, and he planned to do a few laps on his Honda RS750 dirt-tracker at the San Jose Mile—until he found out the promoters had invited the press, so he canceled. He still rides his RC30 sportbike down Highway 1 to Big Sur; he still rides an XR100 on the short track at Kenny Roberts' ranch; and he still rides motocrossers to stay in shape. But there are no immediate plans to return to racing, though he won’t say he's retired—at least not while the tape recorder is running.

“I still haven't given up on racing." Shobert says, when pressed on the matter. “It's hard for me to say I’m giving it up. because 1 get better every day. In my mind, I think I can race, but my coordination and my reflexes . . . you just don't realize how much you have until it's gone.”

What's gone, Shobert says, is his ability to control the right side of his body at the level required to be a professional racer. Typically, he illustrates his problem in racing terms: “1 can stay right with Wayne Rainey and the boys on Kenny’s short track, but when I ride motocross, I can’t go through the right-handers near as fast as the lefts.”

Realizing this, Shobert is wise enough not to tarnish his reputation with a half-hearted comeback attempt.

“I don’t want to race unless 1 can do it like 1 used to,” he says. ”1 don’t feel like I’ve reached that point yet . . . or if I ever will.

“I’m getting older, too. Twentynine don’t seem old. but you can only usually race until you’re 32 or so. You gotta quit sometime. I guess I had to quit earlier than I wanted to.”

So, if Shobert has indeed “quit” racing, what does he think of the accident that ended his career?

“It didn't look that bad to me (on videotape),” Shobert says. “I didn't even feel anything. All the broken bones I had (shoulder, thumb) were healed up by the time I knew what was going on.”

And what does he think of Magee, the person at whom many Shobert fans point damning fingers?

“I know he wasn’t doing it to hurt nobody,” Shobert continues. “It was just a weird thing that doesn’t normally happen. Sometimes, when I think about racing again, I think maybe somebody was trying to warn me that it was time to give it up.” If there’s a hint of newfound religion in what Shobert says, it’s no coincidence. Nor. he says, were the events of a year later, when Magee suffered similar career-threatening head injuries in almost the same place on the same racetrack.

“It kinda lets you know that there’s somebody else controlling everything, I think," Shobert says. “But I don't think Magee deserved it.”

These days, when Shobert does talk of returning to racing, it's not as a rider, but as a team manager, probably fora 1 londa-backed Superbike effort. He admits that he’s spoken to Craig Erion of Two Brothers Racing, and says that if he is able to procure sponsorship, he w'ould like to give a young dirt-tracker the ride. Texas teenager Mike Hale, 1990 AMA Rookie of the Year, is the first rider mentioned.

If Shobert does organize a team, it will be for love of the sport, not for money. A tour of his house high on a hilltop indicates that he is pretty well set for life. There are two garages, one containing an Acura NSX and a fleet of Honda motorcycles, the other stocked with a fishing boat and a home gym. A motocross track encircles the property, and there are two tee boxes from which he whacks golf balls when he’s not out on the links at a local country club. This is a man who made a lot of money during his racing career—$465,700 in Camel bonuses alone.

And it's not like Shobert is unemployed, either. He has a contract with Honda to do public relations and product development, and he also stands to earn royalties from Arai, which is poised to release a Bubba Shobert-model helmet. Add to the equation his new bride, Tara, and son. Clint, and Shobert has plenty of reasons never to risk his neck on a racetrack again.

He still limps sometimes; his signature is different than before; and the little finger on his right hand sticks out at an odd angle. But he insists he's lucky, and he’s thankful for having been given the chance to excel in the sport he loves. “I want to be remembered as a good racer. I wasn’t the best, but I was somebody who always tried, and worked hard for everything I got,” he says.

Even if he never races again. Bubba’s okay. —Brian Catterson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1991 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1991 -

Roundup

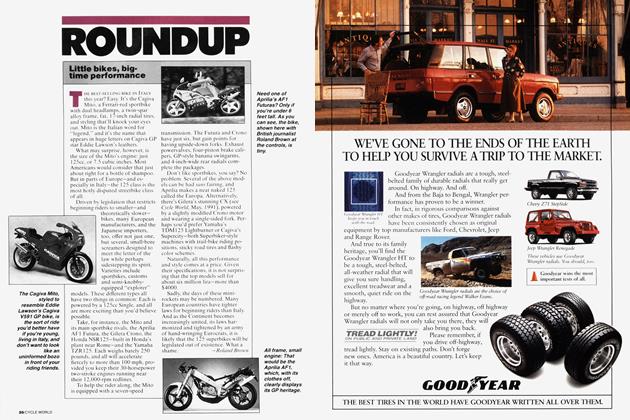

RoundupLittle Bikes, Big-Time Performance

October 1991 By Roland Brown -

Roundup

RoundupJapan's Terrific Tiddlers

October 1991 By Jon F. Thompson