Supercharged Superheroes

RACE WATCH

When it comes to racing Top Fuel dragbikes, mere mortals need not apply.

BRIAN CATTERSON

On the surface, drag racing is as simple as motorsports get: When the green light flashes, you gas it. Whoever crosses the finish line first wins.

But that simplicity is a paradox, because while drag racing’s rules are uncomplicated, its machines are as complex as any motorcycles on the face of the earth. Imagine the technology required to propel a Top Fuel racebike through a quarter-mile-little more than four football fields-in less than seven seconds at over 200 mph.

Strangely, though, these high-tech dragbikes aren't the products of factory-backed racing efforts with mega-dollar sponsorship deals. Rather, they’re the creations of a few dedicated individuals whose mechanical-engineering skills, cultivated largely in backyard workshops, are the stuff more typically found in the aerospace industry.

To find out what makes these earthbound rocketships fly, Associate Editor Don Canet and I ventured to Ateo, New Jersey, to attend the 27th Annual ProStar Orient Express U.S. Nationals. What we found is a motorcycling subculture that is nothing short of mind-blowing.

As a racing facility, Ateo is typical of many on the east coast. Built in 1961, it has seen little in the way of change. Like the rickety bleachers that line it, the dragstrip shows the strains of age, the years of battle with inclement weather, a touch of neglect. It seems an unlikely site for an event billed as the biggest motorcycle drag race of the year, until you learn that Ateo has a reputation as one of the world’s quickest and fastest dragstrips. The fact that it’s situated near sea level, not far from the Atlantic Ocean, and surrounded by trees, gives it near-perfect air for drag-racing motors to breathe. And the track surface, marred only by dips at the end of its twin concrete launching pads and a slight crown in the middle, offers optimum traction. The resultant combination can be magic, especially on a cool, fall evening. It’s no coincidence that we’re here in October.

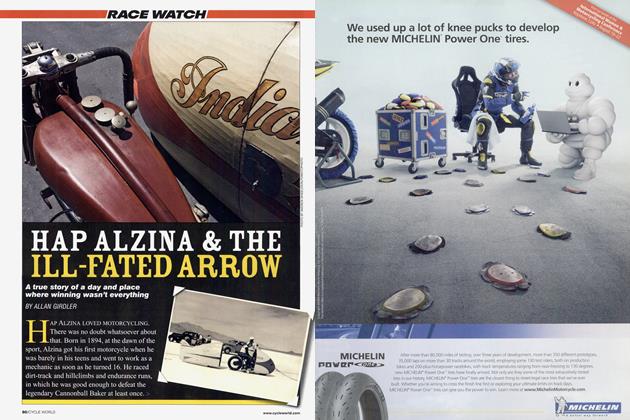

Arriving in time for Thursday’s tune and test session, we find the Ateo pits, while not exactly a hotbed of activity, still pretty lively. We track the sound of a racing motor to its source, where we discover a semi-circle of spectators, drawn like insects to a naked light bulb, all covering their ears. At center is reigning Top Fuel Champion Elmer Trett, blipping the throttle of his “Mountain Magic” Kawasaki. Coming into Ateo, this pairing holds the world record for a drag-racing motorcycle-6.67 seconds at 213 mph.

Those who have never heard a Top Fueler run should attend a drag race for no other reason: The noise is unreal. A twist of the throttle brings Trett’s motor from a staccato idle to a deafening peak-rpm crescendo seemingly in milliseconds. Forget defibrillators-one of these motors could surely jump-start your heart.

How can an engine withstand such abuse? For Trett, the answer is easy: Make everything as big and as strong as possible. Question this hard-looking heavyweight about his bike, and you’ll find that he’s really a good ol’ boy, soft-spoken and a little shy, with answers that are short and to the point. Though his bike is billed as a Kawasaki, a closer look reveals that not much of it was built in Japan. Ask Trett how much and he'll tell you: “The valve cover.” That’s it. The rest is cast, molded, stamped, welded or machined from solid blocks of billet, mostly at his shop, Trett’s Speed & Custom, in the North Georgia Mountains.

With its 13-inch-wide rear slick, 100-inch wheelbase and jutting wheelie bars that increase its overall length to some 16 feet, Trett’s motorcycle is as intimidating in stature as he is. Displacing over 1300cc, the two-valve-per-cylinder inline-Four is force-fed by a Magnusson supercharger, or “blower,” that is driven off the crank and mounted forward of the cylinder block where the exhaust headers would normally be. The unmuffled pipes exit from the rear of the cylinder head and bend upward to pass behind the seat. This routing is said to promote downforce on the rear wheel, increasing traction. With a multi-stage centrifugal clutch and a two-speed automotive transmission, there’s no clutch or shift lever, just a twistgrip for the throttle and a button for the air shifter. The handlebar levers control the front and rear brakes. Running on nitromethane diluted with alcohol, the motor produces 850 horsepower-five times that of the best 500cc grand prix roadracers!

To illustrate just how powerful his bike is, Trett grabs a fellow competitor’s crewman and has him press his weight downward on the idling bike’s front end. With each blip of the throttle, the torque reaction thrusts the crewman upward. Phenomenal. As overwhelming as the sound and power is the smell of burnt nitro. It fills the air, bringing tears to the eyes of even the most ardent onion-peeler.

Pitted near Trett is a Top Fueler that bears more than a passing resemblance to the Bat Mobile-> though it’s painted blue and white. Fittingly, the rider’s leathers identify him as “Spiderman.”

“I don’t know why they call me that,” the rider says in response to my query, “but a few years ago at Indy the announcer called me that and it just stuck.”

As it turns out, the rider’s real name is Larry McBride. A lanky sixfooter who owns Cycle Specialists in Newport News, Virginia, McBride won here last year, and he’s the guy Trett-and everyone else-will be gunning for this weekend. McBride has been experimenting with a new type of supercharger on his Suzuki GS1150-based racebike, and has been going seriously fast. Banned for car use by the National Hot Rod Association because of alleged supply problems, the blower is called a Sprintex, and it differs from the popular Magnusson unit in that it uses screw-type-rather than vane-typeblades. On McBride’s bike, the blower is positioned where the carburetors would normally be, and it breathes air through a plenum that hangs out in the airstream on the left side of the cylinder bank.

Typical of this sport’s brand of home-brewed ingenuity, McBride makes his own fuel-management systems, and has fitted a computer that monitors his bike’s vital signs-fuel pressure, blower boost, exhaust temperature, engine and output-shaft rpm, even g-forces.

Friday night, I hike down to the far end of the dragstrip to watch the bikes in full flight. I’m glad I did, because McBride’s first qualifying run is one to remember. Standing be hind the guard rail adjacent to the timing lights, I can barely see McBride as he performs his tirewarming burnout and stages a quarter-mile away. The lights flash green, and almost before I can hear the engine, he’s on me, flames shooting from the exhausts as he passes by at a velocity that just plain sucks the wind out of my lungs. With his elbows and legs flailing as he shifts his weight to keep the bike going straight and the front wheel more or less on the ground, I realize how he got his nickname.

Awestruck, I stand there with my mouth wide open, sensing that this was no ordinary run. Turning to the huge scoreboard, my suspicions are confirmed: 6.58/218, it reads-a new world record. Or maybe not. McBride’s time, I’m informed, is not yet a new record; he’ll have to make another pass within one percent as quick for the mark to be official. (Trett, in fact, recorded the quickest time ever-a 6.53/219-at Ateo last year, but was unable to back it up.)

As for Trett, he breaks a blower belt during his first qualifying pass and has to wait until the next day for another chance. True to form, he eclipses McBride’s time Saturday morning, turning a 6.51/217 to become the number-one qualifier, and to again have a shot at a new world record. During the third and final round of qualifying that afternoon, Trett and Englishman Brian Johnson become the first pair ever to record simultaneous 6-second/200-mph passes, but Trett’s time isn’t quick enough to back up his previous run.

McBride, however, is able to back up his previous night’s pass, turning a 6.64/208 to cement his world record. The other seven riders attempting to qualify for the eightbike field don’t even break into the Sixes.

First-round eliminations commence Sunday morning, and predictably, McBride and Trett are the stars of the show. Trett, in fact, throws a rod at the eighth-mile mark and still bests his opponent. Asked if his bike is always this hard on parts, Trett is elusive. “Sometimes it is, sometimes it isn’t,” he replies.

McBride, meanwhile, cruises to an uncontested victory (a “bye run”) when his competitor has mechanical problems and doesn’t stage. McBride’s bike proves to be pretty reliable, needing only a new set of exhaust valves after each run; when they’re in a hurry, the crew saves time by swapping complete cylinder heads.

Sunday morning’s clouds give way to afternoon rain, and the event is a washout, postponed to Monday. The racing is worth waiting for, however, because conditions are perfect the next day. In second-round eliminations, Trett, with a replacement motor, is caught napping at the line, but he defeats Brian Johnson anyway when the Englishman has to roll off to keep from crossing the centerline. And McBride receives the gift of another bye run when his competitor, unable to change airline tickets, is a noshow-most drag racers have to go to work on Monday. In the process, he uncorks another fire-breathing pass, a 6.49/214, to lower his record.

As if there were ever any question, the finals pit Trett against McBride in what promises to be a great race. Trett, however, can’t deliver on that promise: He fails to heat the tire properly during his burnout, and when the green light flashes, the tire goes up in smoke. McBride is the winner with a record-tying 6.49, this time one mph slower at 213, besting Trett’s 7.61/203. A bit anticlimactic after the long buildup, perhaps, but a fitting conclusion to a thrilling weekend of racing, nonetheless.

Later that evening, with my head still reeling-and my ears still ringing-from the spectacle, I contemplate what I’ve learned this weekend. And there’s one thing that baffles me: Despite the fact that they are the quickest and fastest dragbikes in the world, Top Fuelers carry mere sideshow status. In the grand scheme of things, the NHRA’s Pro Stock class is considered the most prestigious form of motorcycle drag racing in America.

The NHRA used to feature Top Fuel bikes, but eliminated the class because, depending on who you believe, (a) insurance rates skyrocketed, (b) entries dropped or (c) the equipment became unrecognizable, and thus unmarketable for the manufacturers.

No doubt the Pro Stock formula, with it’s reliance on productionbased streetbikes, makes for close racing, but can it ever be as spectacular as Top Fuel? Pro Stock bikes, in fact, were included at Atco-as a support class-and the winner, Vance & Hines’ Dave Schultz, set a new record at 7.63/177, still 1.14 seconds and 36 mph slower than McBride’s winning Top Fuel pass.

Top Fuel may be on the rebound, though. “The NHRA has contacted Elmer and me about bringing Top Fuel back on an exhibition basis next year,” explains McBride. “They originally dropped us because there weren’t enough reliable, competitive entries. But I think, these days, our quality of competition, appearance and reliability would make for an excellent show.” An NHRA spokesman confirmed this, saying that the class is indeed being written into the 1992 rulebook.

Even so, Pro Stock standout Dave Schultz doesn’t see Top Fuel becoming the featured class anytime soon. “There just aren’t enough entries,” he says. “We get 20 or more Pro Stock entries for a 16-bike field at an NHRA event. You couldn’t do that with Top Fuel. It’ll take at least three years for it to make the jump from ‘show’ status to a Pro racing class.”

Whether or not that happens, and when-if ever-Top Fuel is once again the premier form of motorcycle drag racing, remains to be seen. Until then, Top Fuel’s supercharged superheroes will continue to flex their muscles in the ProStar ranks, confident in the knowledge that no matter how much media exposure or money the Pro Stock racers get, Top Fuelers are motorcycling’s real Top Guns. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSex Lessons

FEBRUARY 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBoots And Saddles

FEBRUARY 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Cannon Connection

FEBRUARY 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1992 -

Roundup

RoundupAll-New Bmw Twin: Tradition Takes A Turn

FEBRUARY 1992 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Little Engine That Thinks Big

FEBRUARY 1992 By Yasushi Ichikawa