Suzuki’s little engine that thinks big

ROUNDUP

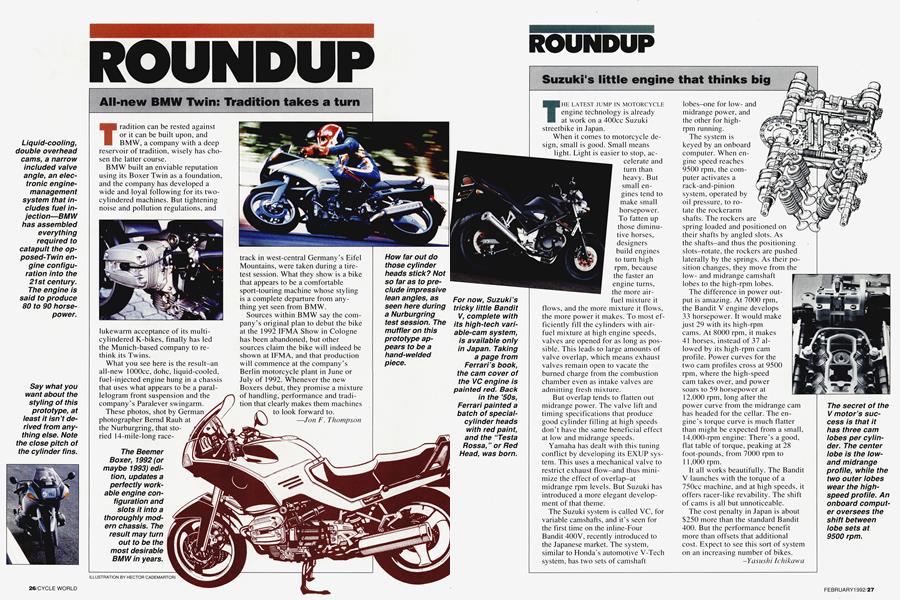

THE LATEST JUMP IN MOTORCYCLE engine technology is already at work on a 400cc Suzuki streetbike in Japan.

When it comes to motorcycle design, small is good. Small means light. Light is easier to stop, accelerate and turn than heavy. But small engines tend to make small horsepower. To fatten up those diminutive horses, designers build engines to turn high rpm, because the faster an engine turns, the more airfuel mixture it

flows, and the more mixture it flows, the more power it makes. To most efficiently fill the cylinders with airfuel mixture at high engine speeds, valves are opened for as long as possible. This leads to large amounts of valve overlap, which means exhaust valves remain open to vacate the burned charge from the combustion chamber even as intake valves are admitting fresh mixture.

But overlap tends to flatten out midrange power. The valve lift and timing specifications that produce good cylinder filling at high speeds don’t have the same beneficial effect at low and midrange speeds.

Yamaha has dealt with this tuning conflict by developing its EXUP system. This uses a mechanical valve to restrict exhaust flow-and thus minimize the effect of overlap-at midrange rpm levels. But Suzuki has introduced a more elegant development of that theme.

The Suzuki system is called VC, for variable camshafts, and it’s seen for the first time on the inline-Four Bandit 400V, recently introduced to the Japanese market. The system, similar to Honda's automotive V-Tech system, has two sets of camshaft

lobes-one for lowand midrange power, and the other for highrpm running.

The system is keyed by an onboard computer. When engine speed reaches 9500 rpm, the computer activates a rack-and-pinion system, operated by oil pressure, to rotate the rockerarm shafts. The rockers are spring loaded and positioned on their shafts by angled slots. As the shafts-and thus the positioning slots-rotate, the rockers are pushed laterally by the springs. As their po sition changes, they move from the lowand midrange camshaft lobes to the high-rpm lobes.

The difference in power output is amazing. At 7000 rpm, the Bandit V engine develops 33 horsepower. It would make just 29 with its high-rpm cams. At 8000 rpm, it makes 41 horses, instead of 37 allowed by its high-rpm cam profile. Power curves for the two cam profiles cross at 9500 rpm, where the high-speed cam takes over, and power soars to 59 horsepower at

12.000 rpm, long after the power curve from the midrange cam has headed for the cellar. The engine’s torque curve is much flatter than might be expected from a small, 14,000-rpm engine: There’s a good, flat table of torque, peaking at 28 foot-pounds, from 7000 rpm to 11.000 rpm.

It all works beautifully. The Bandit V launches with the torque of a 750cc machine, and at high speeds, it offers racer-like revability. The shift of cams is all but unnoticeable.

The cost penalty in Japan is about $250 more than the standard Bandit 400. But the performance benefit more than offsets that additional cost. Expect to see this sort of system on an increasing number of bikes.

Yasushi Ichikawa

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSex Lessons

FEBRUARY 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBoots And Saddles

FEBRUARY 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Cannon Connection

FEBRUARY 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1992 -

Roundup

RoundupAll-New Bmw Twin: Tradition Takes A Turn

FEBRUARY 1992 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

FEBRUARY 1992 By Jon F. Thompson