Boots and saddles

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

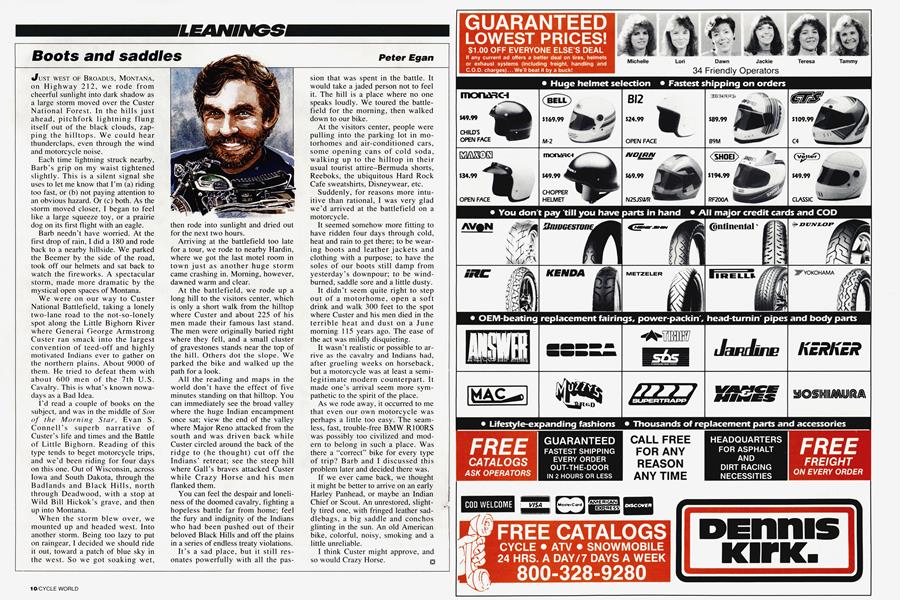

JUST WEST OF BROADUS, MONTANA, on Highway 212, we rode from cheerful sunlight into dark shadow as a large storm moved over the Custer National Forest. In the hills just ahead, pitchfork lightning flung itself out of the black clouds, zapping the hilltops. We could hear thunderclaps, even through the wind and motorcycle noise.

Each time lightning struck nearby, Barb’s grip on my waist tightened slightly. This is a silent signal she uses to let me know that I’m (a) riding too fast, or (b) not paying attention to an obvious hazard. Or (c) both. As the storm moved closer, I began to feel like a large squeeze toy, or a prairie dog on its first flight with an eagle.

Barb needn’t have worried. At the first drop of rain, I did a 180 and rode back to a nearby hillside. We parked the Beemer by the side of the road, took off our helmets and sat back to watch the fireworks. A spectacular storm, made more dramatic by the mystical open spaces of Montana.

We were on our way to Custer National Battlefield, taking a lonely two-lane road to the not-so-lonely spot along the Little Bighorn River where General George Armstrong Custer ran smack into the largest convention of teed-off and highly motivated Indians ever to gather on the northern plains. About 9000 of them. He tried to defeat them with about 600 men of the 7th U.S. Cavalry. This is what’s known nowadays as a Bad Idea.

I’d read a couple of books on the subject, and was in the middle of Son of the Morning Star, Evan S. Connell’s superb narrative of Custer’s life and times and the Battle of Little Bighorn. Reading of this type tends to beget motorcycle trips, and we’d been riding for four days on this one. Out of Wisconsin, across Iowa and South Dakota, through the Badlands and Black Hills, north through Deadwood, with a stop at Wild Bill Hickok’s grave, and then up into Montana.

When the storm blew over, we mounted up and headed west. Into another storm. Being too lazy to put on raingear, I decided we should ride it out, toward a patch of blue sky in the west. So we got soaking wet, then rode into sunlight and dried out for the next two hours.

Arriving at the battlefield too late for a tour, we rode to nearby Hardin, where we got the last motel room in town just as another huge storm came crashing in. Morning, however, dawned warm and clear.

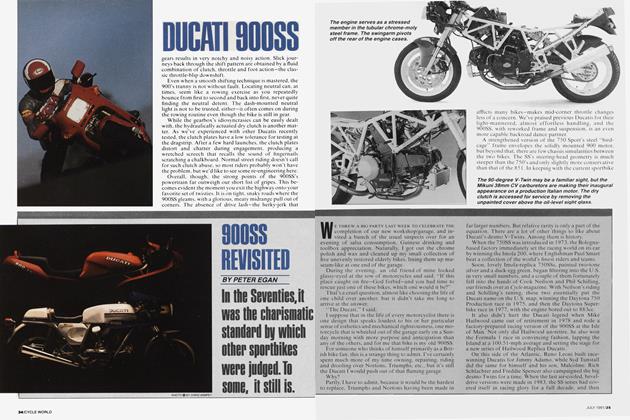

At the battlefield, we rode up a long hill to the visitors center, which is only a short walk from the hilltop where Custer and about 225 of his men made their famous last stand. The men were originally buried right where they fell, and a small cluster of gravestones stands near the top of the hill. Others dot the slope. We parked the bike and walked up the path for a look.

All the reading and maps in the world don’t have the effect of five minutes standing on that hilltop. You can immediately see the broad valley where the huge Indian encampment once sat; view the end of the valley where Major Reno attacked from the south and was driven back while Custer circled around the back of the ridge to (he thought) cut off the Indians’ retreat; see the steep hill where Gall’s braves attacked Custer while Crazy Horse and his men flanked them.

You can feel the despair and loneliness of the doomed cavalry, fighting a hopeless battle far from home; feel the fury and indignity of the Indians who had been pushed out of their beloved Black Hills and off the plains in a series of endless treaty violations.

It’s a sad place, but it still resonates powerfully with all the passion that was spent in the battle. It would take a jaded person not to feel it. The hill is a place where no one speaks loudly. We toured the battlefield for the morning, then walked down to our bike.

At the visitors center, people were pulling into the parking lot in motorhomes and air-conditioned cars, some opening cans of cold soda, walking up to the hilltop in their usual tourist attire-Bermuda shorts, Reeboks, the ubiquitous Hard Rock Cafe sweatshirts, Disneywear, etc.

Suddenly, for reasons more intuitive than rational, I was very glad we’d arrived at the battlefield on a motorcycle.

It seemed somehow more fitting to have ridden four days through cold, heat and rain to get there; to be wearing boots and leather jackets and clothing with a purpose; to have the soles of our boots still damp from yesterday’s downpour; to be windburned, saddle sore and a little dusty.

It didn’t seem quite right to step out of a motorhome, open a soft drink and walk 300 feet to the spot where Custer and his men died in the terrible heat and dust on a June morning 115 years ago. The ease of the act was mildly disquieting.

It wasn’t realistic or possible to arrive as the cavalry and Indians had, after grueling weeks on horseback, but a motorcycle was at least a semilegitimate modern counterpart. It made one’s arrival seem more sympathetic to the spirit of the place.

As we rode away, it occurred to me that even our own motorcycle was perhaps a little too easy. The seamless, fast, trouble-free BMW R100RS was possibly too civilized and modern to belong in such a place. Was there a “correct” bike for every type of trip? Barb and I discussed this problem later and decided there was.

If we ever came back, we thought it might be better to arrive on an early Harley Panhead, or maybe an Indian Chief or Scout. An unrestored, slightly tired one, with fringed leather saddlebags, a big saddle and conchos glinting in the sun. An old American bike, colorful, noisy, smoking and a little unreliable.

I think Custer might approve, and so would Crazy Horse.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSex Lessons

FEBRUARY 1992 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCThe Cannon Connection

FEBRUARY 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1992 -

Roundup

RoundupAll-New Bmw Twin: Tradition Takes A Turn

FEBRUARY 1992 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Little Engine That Thinks Big

FEBRUARY 1992 By Yasushi Ichikawa -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

FEBRUARY 1992 By Jon F. Thompson