Tipping over

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

IT WAS AN ALMOST-PERFECT ILLUSTRAtion of Egan’s First Law of Physics, which is: A falling motorcycle, once in motion, tends to remain in motion unless acted upon by three or four guys who have the presence of mind to drop their beers and streak to the rescue.

Here’s the scene:

Nice summer evening, monthly meeting of the Slimey Crud Motorcycle Gang, this time at the home of our venerated president, Dr. Kenneth Clark, a person of remarkable sanity and clarity of thought, considering he has a PhD in Psychology, a pursuit which has ruined lesser intellects. At least a dozen of us are standing in Dr. Clark’s driveway, admiring our bikes and the bikes of others while sipping on the various bottles of dark, heavy, “small label” beers and ales we each bring to these events in our never-ending search for Nirvana, as imagined by Bavarians and British dart players.

Up rides long-standing Crud, intrepid muskie fisherman and police officer Mike Puls, who is also our road captain and supplier of huge dead fish for the ritualistic tribal dinners that mark these occasions. Mike is riding his new/used, very red Ducati 907ie, which he has just purchased that very afternoon. This is his first ride on it.

We all gawk and admire for a while this new bike, which you will recall has fully enveloping bodywork, like a blood-red Fabergé egg on wheels, and one of the nicest engines in all of motorcycling, with a V-Twin exhaust note to match. Soon the admirers are taking short test rides.

One of them, who shall remain nameless because it could have happened to any of us (and has), returns from a short ride, attempts to turn around in the driveway while threading his way past other bikes and runs into the dreaded Ducati absence of steering lock. This causes the bike to do its traditional low-speed high-side tip-over. The rider makes a valiant attempt to catch the bike, but of course it’s hopeless. The front wheel dollies out from under him and he lays it down in a small explosion of mirror smithereens and splintering, cracking plastic.

Owner Mike, who is talking to me at the moment, says quietly, “Oh, no....”

The 12 of us who are looking on do nothing, knowing from experience that we will be too late and picturing the futile mess of 12 dropped beer bottles on the concrete driveway. Tipping over, like injury in battle, is a small, personal moment of private hell. No one can undo it.

The bill for this brief ballet will be $1100, on a bike that cost $5600 used. Faired-in mirror smashed, three separate body panels crunched, punctured or scraped. Seems an excessive price for such a brief misjudgment; almost as bad as sex in high school.

We’ll call the above unhappy incident Scene I. Roll the clock back a few months and return with me now to Scene II.

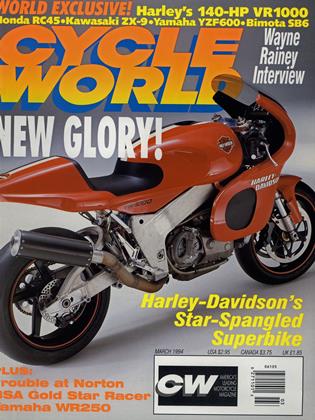

It is last spring and we are in the Alps, Editor David Edwards and I, on the Cycle Hbr/iZ/Edelweiss GP EuroTour with a dozen or more other riders. We are stopped at a gas station somewhere in Austria. David is riding a BMW R100GS-PD, the redoubtable Paris-Dakar Boxer with its 9.3-gallon gas tank. I have been riding a BMW K75S for the past three days, and we agree to switch bikes for the afternoon.

I am standing around at the gas station, jawing with an Austrian passerby who speaks excellent English, when I suddenly realize that everyone is fueled, mounted up and leaving. Pulling on my helmet, I jog across the drive and make a kind of Hopalong Cassidy leap into the saddle of the very tall Beemer. I jerk the bike upright off its sidestand, and lo and behold it just keeps going (a falling

motorcycle, once in motion...etc.).

And going. I put one leg out for support, but the angle is wrong because I’m so high off the ground. The bike crashes to the ground with a sickening thud that can be picked up by anxious seismologists in San Juan Capistrano.

Five or six of us and a team of horses manage to get the tall, top-heavy bike back up on its sidestand. It would be nice to have the excuse that the 9.3gallon gas tank was full, but it was not. Typical of these bikes, David hasn’t filled it since yesterday, and it’s only about half-full. Maybe I could blame slosh factor, but mostly I’ve just Bozed-out by trying to be some kind of hotshot. Pride goeth before a fall.

Inspecting the Beemer for damage, we discover-nothing.

Well, almost nothing. There’s a minor blemish in the paint on the crashbar that surrounds the cylinder heads...a small white rough spot on the end of the handgrip rubber...a nearly indiscernible scuff on one turnsignal. Nearly all evidence disappears with a little spit and rubbing with a rag. If it were my own bike, I could shrug it off and forget it, not replacing or repainting a thing.

Frankly, I liked the outcome of this latter incident better than the Ducati scenario.

Granted, a BMW R100GS is an extreme case in point, because these motorcycles are almost made to be dropped. But with the cost of body panels on fully faired bikes these days (and our subsequent insurance rates), I’m not sure it doesn’t make sense to build in at least a modicum of tip-over protection on any bike that has a lot to lose by crashing to the pavement-pure racing machines excepted.

Honda’s Pacific Coast, with its padded bumpers built into the outer edge of the fairing, is a nice example of what can be done. When you consider the poor odds that any two-wheeled vehicle will remain upright during its many years of service, some constructive bet-hedging is not a bad idea.

A little thoughtful engineering might go a long way toward mitigating the effects of Egan’s Second Law of Physics, which is: An expensive new motorcycle that belongs to someone else is unstable in direct proportion to the number of people watching.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue