The basement

TDC

Kevin Cameron

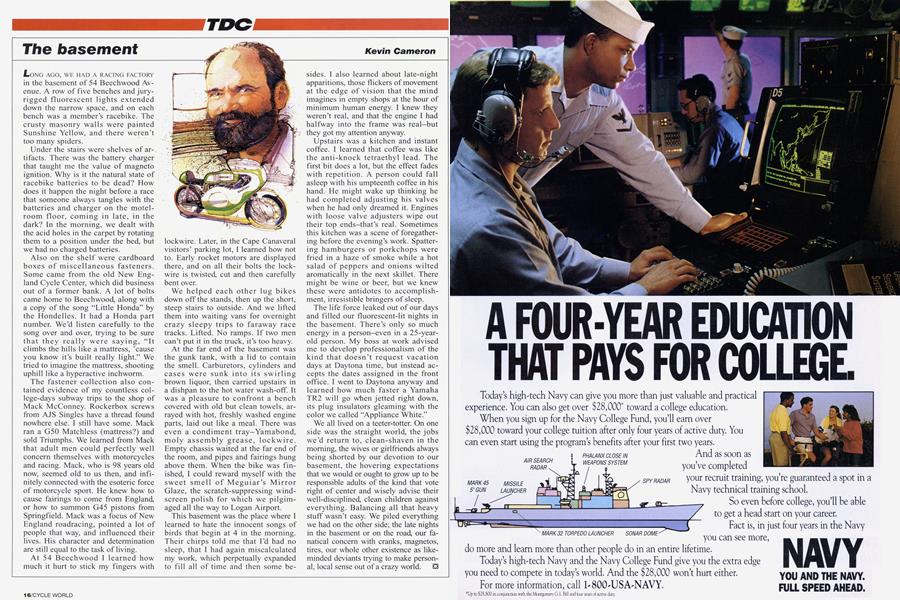

LONG AGO, WE HAD A RACING FACTORY in the basement of 54 Beechwood Avenue. A row of five benches and jury-rigged fluorescent lights extended down the narrow space, and on each bench was a member’s racebike. The crusty masonry walls were painted Sunshine Yellow, and there weren’t too many spiders.

Under the stairs were shelves of ar-, tifacts. There was the battery charger that taught me the value of magneto ignition. Why is it the natural state of racebike batteries to be dead? How does it happen the night before a race that someone always tangles with the batteries and charger on the motelroom Hoor, coming in late, in the dark? In the morning, we dealt with the acid holes in the carpet by rotating them to a position under the bed, but we had no charged batteries.

Also on the shelf were cardboard boxes of miscellaneous fasteners. Some came from the old New England Cycle Center, which did business out of a former bank. A lot of bolts came home to Beechwood, along with a copy of the song “Little Honda” by the Hondelles. It had a Honda part number. We’d listen carefully to the song over and over, trying to be sure that they really were saying, “It climbs the hills like a mattress, ’cause you know it’s built really light.” We tried to imagine the mattress, shooting uphill like a hyperactive inchworm.

The fastener collection also contained evidence of my countless college-days subway trips to the shop of Mack McConney. Rockerbox screws from AJS Singles have a thread found nowhere else. I still have some. Mack ran a G50 Matchless (mattress?) and sold Triumphs. We learned from Mack that adult men could perfectly well concern themselves with motorcycles and racing. Mack, who is 98 years old now, seemed old to us then, and infinitely connected with the esoteric force of motorcycle sport. He knew how to cause fairings to come from England, or how to summon G45 pistons from Springfield. Mack was a focus of New England roadracing, pointed a lot of people that way, and influenced their lives. His character and determination are still equal to the task of living.

At 54 Beechwood I learned how much it hurt to stick my fingers with lockwire. Later, in the Cape Canaveral visitors’ parking lot, I learned how not to. Early rocket motors are displayed there, and on all their bolts the lockwire is twisted, cut and then carefully bent over.

We helped each other lug bikes down off the stands, then up the short, steep stairs to outside. And we lifted them into waiting vans for overnight crazy sleepy trips to faraway race tracks. Lifted. No ramps. If two men can’t put it in the truck, it’s too heavy.

At the far end of the basement was the gunk tank, with a lid to contain the smell. Carburetors, cylinders and cases were sunk into its swirling brown liquor, then carried upstairs in a dishpan to the hot water wash-off. It was a pleasure to confront a bench covered with old but clean towels, arrayed with hot, freshly washed engine parts, laid out like a meal. There was even a condiment tray-Yamabond, moly assembly grease, lockwire. Empty chassis waited at the far end of the room, and pipes and fairings hung above them. When the bike was finished, I could reward myself with the sweet smell of Meguiar’s Mirror Glaze, the scratch-suppressing windscreen polish for which we pilgimaged all the way to Logan Airport.

This basement was the place where I learned to hate the innocent songs of birds that begin at 4 in the morning. Their chirps told me that I’d had no sleep, that I had again miscalculated my work, which perpetually expanded to fill all of time and then some be-

sides. I also learned about late-night apparitions, those flickers of movement at the edge of vision that the mind imagines in empty shops at the hour of minimum human energy. I knew they weren’t real, and that the engine I had halfway into the frame was real-but they got my attention anyway.

Upstairs was a kitchen and instant coffee. I learned that coffee was like the anti-knock tetraethyl lead. The first bit does a lot, but the effect fades with repetition. A person could fall asleep with his umpteenth coffee in his hand. He might wake up thinking he had completed adjusting his valves when he had only dreamed it. Engines with loose valve adjusters wipe out their top ends-that’s real. Sometimes this kitchen was a scene of foregathering before the evening’s work. Spattering hamburgers or porkchops were fried in a haze of smoke while a hot salad of peppers and onions wilted aromatically in the next skillet. There might be wine or beer, but we knew these were antidotes to accomplishment, irresistible bringers of sleep.

The life force leaked out of our days and filled our fluorescent-lit nights in the basement. There’s only so much energy in a person-even in a 25-yearold person. My boss at work advised me to develop professionalism of the kind that doesn’t request vacation days at Daytona time, but instead accepts the dates assigned in the front office. I went to Daytona anyway and learned how much faster a Yamaha TR2 will go wtien jetted right down, its plug insulators gleaming with the color we called “Appliance White.”

We all lived on a teeter-totter. On one side was the straight world, the jobs we’d return to, clean-shaven in the morning, the wives or girlfriends always being shorted by our devotion to our basement, the hovering expectations that we would or ought to grow up to be responsible adults of the kind that vote right of center and wisely advise their well-disciplined, clean children against everything. Balancing all that heavy stuff wasn’t easy. We piled everything we had on the other side; the late nights in the basement or on the road, our fanatical concern with cranks, magnetos, tires, our whole other existence as likeminded deviants trying to make personal, local sense out of a crazy world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue