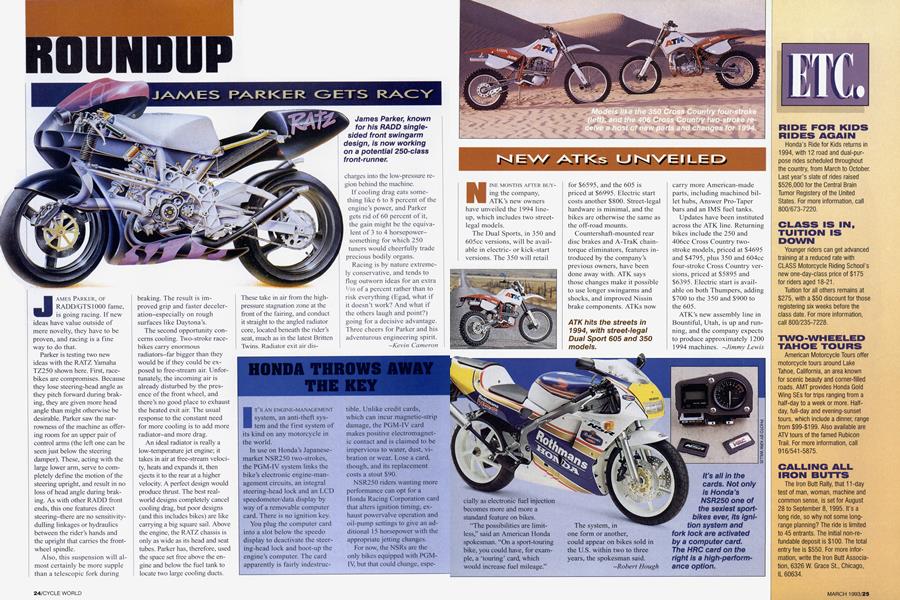

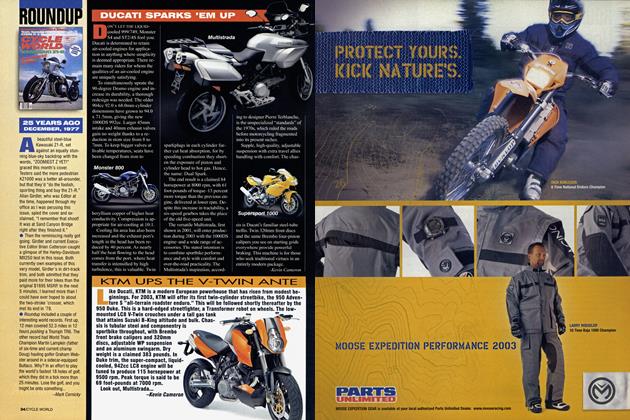

JAMES PARKER GETS RACY

ROUNDUP

JAMES PARKER, OF RADD/GTS1000 fame, is going racing. If new ideas have value outside of mere novelty, they have to be proven, and racing is a fine way to do that.

Parker is testing two new ideas with the RATZ Yamaha TZ250 shown here. First, racebikes are compromises. Because they lose steering-head angle as they pitch forward during braking, they are given more head angle than might otherwise be desirable. Parker saw the narrowness of the machine as offering room for an upper pair of control arms (the left one can be seen just below the steering damper). These, acting with the large lower arm, serve to completely define the motion of the steering upright, and result in no loss of head angle during braking. As with other RADD front ends, this one features direct steering-there are no sensitivitydulling linkages or hydraulics between the rider’s hands and the upright that carries the frontwheel spindle.

Also, this suspension will almost certainly be more supple than a telescopic fork during braking. The result is improved grip and faster deceleration-especially on rough surfaces like Daytona’s.

The second opportunity concerns cooling. Two-stroke racebikes carry enormous radiators—far bigger than they would be if they could be exposed to free-stream air. Unfortunately, the incoming air is already disturbed by the presence of the front wheel, and there’s no good place to exhaust the heated exit air. The usual response to the constant need for more cooling is to add more radiator-and more drag.

An ideal radiator is really a low-temperature jet engine; it takes in air at free-stream velocity, heats and expands it, then ejects it to the rear at a higher velocity. A perfect design would produce thrust. The best realworld designs completely cancel cooling drag, but poor designs (and this includes bikes) are like carrying a big square sail. Above the engine, the RATZ chassis is only as wide as its head and seat tubes. Parker has, therefore, used the space set free above the engine and below the fuel tank to locate two large cooling ducts. These take in air from the highpressure stagnation zone at the front of the fairing, and conduct it straight to the angled radiator core, located beneath the rider’s seat, much as in the latest Britten Twins. Radiator exit air discharges into the low-pressure region behind the machine.

If cooling drag eats something like 6 to 8 percent of the engine’s power, and Parker gets rid of 60 percent of it, the gain might be the equivalent of 3 to 4 horsepowersomething for which 250 tuners would cheerfully trade precious bodily organs.

Racing is by nature extremely conservative, and tends to flog outworn ideas for an extra Vio of a percent rather than to risk everything (Egad, what if it doesn’t work? And what if the others laugh and point?) going for a decisive advantage. Three cheers for Parker and his adventurous engineering spirit.

Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue