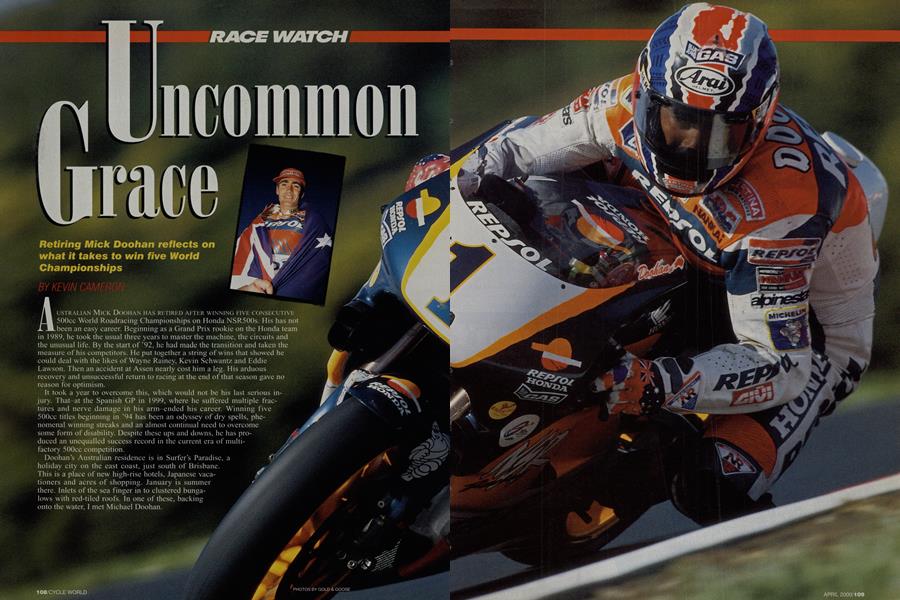

Uncommon Grace

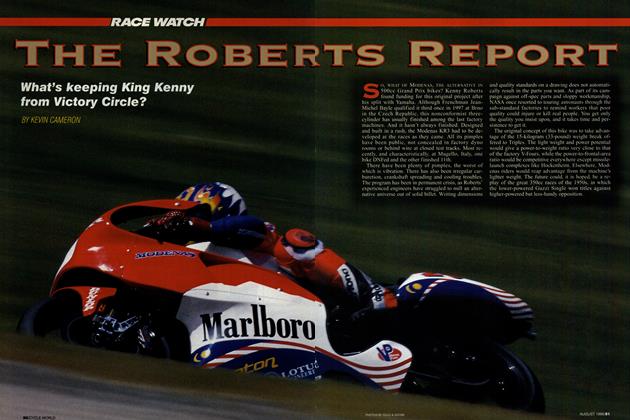

RACE WATCH

Retiring Mick Doohan reflects on what it takes to win five World Championships

KEVIN CAMERON

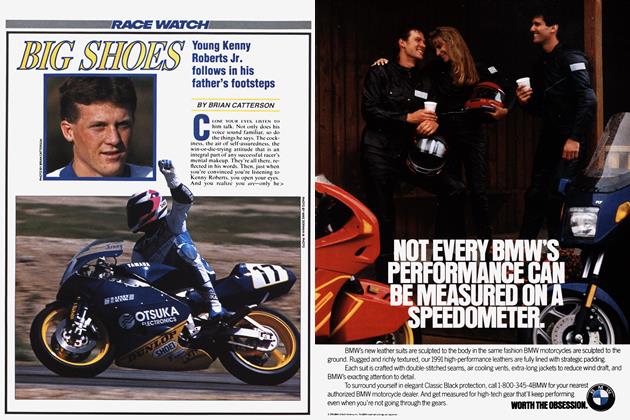

AUSTRALIAN MICK DOOHAN HAS RETIRED AFTER WINNING FIVE CONSECUTIVE 500cc World Roadracing Championships on Honda NSR500s. His has not been an easy career. Beginning as a Grand Prix rookie on the Honda team in 1989, he took the usual three years to master the machine, the circuits and the unusual life. By the start of ’92, he had made the transition and taken the measure of his competitors. He put together a string of wins that showed he could deal with the likes of Wayne Rainey, Kevin Schwantz and Eddie Lawson. Then an accident at Assen nearly cost him a leg. His arduous recovery and unsuccessful return to racing at the end of that season gave no reason for optimism.

It took a year to overcome this, which would not be his last serious injury. That-at the Spanish GP in 1999, where he suffered multiple fractures and nerve damage in his arm-ended his career. Winning five 500cc titles beginning in ’94 has been an odyssey of dry spells, phenomenal winning streaks and an almost continual need to overcome some form of disability. Despite these ups and downs, he has pro duced an unequalled success record in the current era of multifactory 5()0cc competition.

Doohan’s Australian residence is in Surfer’s Paradise, a holiday city on the east coast, just south of Brisbane.

This is a place of new high-rise hotels, Japanese vacationers and acres of shopping. January is summer there. Inlets of the sea finger in to clustered bungalows with red-tiled roofs. In one of these, backing onto the water, I met Michael Doohan. mf

“I’ve never really lived here,” he remarked, indicating the open-plan first floor with minimal furnishings. Four NSR500s can be seen, with another to come-one for each championship-and there is a crowded 12-foot glass trophy cabinet. For tax purposes, Doohan also maintains a house in Monaco, but racing and domesticity mix imperfectly.

We sat at the kitchen table, he pushing aside aviation magazines and a stack of baby’s bibs. Doohan and partner Selina have a 6-month-old girl, Alexis.

Doohan’s appearance is distinguished, like that of a fast-rising, respected university professor. His manner is watchful, self-contained, not forthcoming. He waits for questions, answers economically, and waits again.

began by asking about the wellpublicized differences between the two types of NSR engines-the “Big Bang” engine, which fires cylinder pairs simultaneously, spaced at just under 70 degrees, and the “Screamer,” which fires its pairs at even, 180-degree intervals.

“It’s all about wheelspin,” he began. “If you have wheelspin, it heats the tire and then the tire doesn’t last. The Big Bang was just one way of controlling wheelspin.”

In Doohan’s first GP season, 1989, 500cc engines had violent powerbands, the onset of which provoked wheelspin no matter who the rider was. Corner exits were a series of slip-and-grip slides that threatened to high-side the rider. The first technology used against this was the electronic torque controls of 1991. What I wanted to know was, did the Big Bang actually increase acceleration, or did it just improve control?

Doohan brushed the form of my question away as irrelevant. He obviously did not care how wheelspin was controlled, so long as the result was adequate tire life.

I asked about how he had managed relations with Honda engineers. Engineers like to “improve” things that can be measured like weight and power.

Riders’ objectives can’t be quantified. Championships are won on machines that are tailored in detail to suit rider style, not engineered to numbers. “The engineers listen to us about 90 percent of the time. I say 90 because engineers want to do what engineers do.” Smiling slightly, he continued: “And not everything we suggest works, but it works

often enough that we have a good working relationship.

“The main thing we accomplished, really, was to get them to stop making a completely new motorcycle every year. We wanted to keep the parts that did a good job, and just work on the problems we had.”

I asked if his motorcycle had been affected by the fashion for “calibrated chassis flex” that swept over Honda in 1996-97.

“No, not really. If you’re 5 seconds off the pace, that bit of flexibility makes the motorcycle feel better. So the (factory) test rider is developing a motorcycle for himself, one that makes him feel confident. But at the limit, it doesn’t have the feel.”

Honda had built such a chassis for the NSR, Doohan continued, but he had rejected it. If a new item such as a chassis or fork did not show value in a few laps, he moved on to more promising setups. GP racing is always short on time.

“As far as I’m concerned the chassis is just something that holds the wheels together. What determines the character of a motorcycle more than anything else is its suspension. You can change units-not just settings but units-and have a machine that handles completely different.”

Doohan has said elsewhere that the recent Hondas have been one-line motorcycles as compared with the latest Yamaha and Suzuki, which can turn tighter or change line at will.

“We had a new chassis-something completely different-that we were working on. I didn’t race it, but I had three bikes and we’d test with that one when there was time.” He seemed to regret leaving this experiment incomplete.

I asked about Showa’s attempts to get him to test new-design forks in recent years. Again, he replied that there was never time to spend more than a few laps on anything that was not clearly part of the way ahead.

“We bought an Öhlins fork and tested with it. I couldn’t race with it because of Honda’s special relationship with Showa. When we put it on-with no adjustments-straightaway it was a halfsecond a lap quicker. It was smoother.”

This unwillingness to spend time on novelties related directly to Doohan’s basic attitude toward riding the motorcycle. He was known for riding every lap of practice, race or test, as hard and fast as he could.

“That’s your opportunity to learn something,” he said, simply, implying that anyone who just “rolls around the circuit” is wasting time. In direct costs, each lap on a 500cc GP bike is something like $3000. Riding at less than 100 percent effort is, therefore, just very expensive personal transportation. Because nothing can be learned at less than 100 percent, it

makes sense to ride only at that level, and at every opportunity. Doohan’s legendary 100 percent riding effort is therefore just common sense in his terms. Because so many other riders practice and test as if breaking in new footrests, this common sense is not obvious to all.

Doohan’s competitiveness is legend, yet he remained largely aloof from the off-track cut-and-thrust of some of his rivals. How, I asked him, did you manage your competitiveness?

“Any competitive activity that is not directed at winning on Sunday is a waste,” he replied, succinctly. “You see two riders out in practice, and one outbrakes the other just to do it-they’re getting in each other’s way, really. Just racing from corner to corner, not thinking about how to win the race. When I met another rider in the paddock, I just said, ‘Hello.’ I didn’t want to give anyone any more reason to want to beat me on Sunday than he already had.”

More Mick Doohan common senseand yet not so obvious to others.

Doohan’s most recent style involved the use of fairly high corner speed, and his manner of coming on-throttle was correspondingly smooth and gradual. At high lean angle, the tire has little extra grip available for acceleration. I therefore asked him how he dealt with “Twins Syndrome.” Halfliter Twins like Honda’s privateer NSR500V must make their lap times on corner speed because they lack acceleration. But as the back tire deteriorates during a race, this advantage is lost and the rider must slow. The same problem arises on four-cylinder bikes whose riders use high lean angles.

“On some tracks-tracks that favor 250s-the point-and-shoot style is actually a handicap,” he began.

Point-and-shoot is the style of entering turns at less than maximum possible speed, getting the turning done early on a tighter radius, then using the remaining part of the turn as a launch pad for early acceleration. The current generation of young 500 riders have come up from 250 racing, and ride the high-corner-speed 250 style.

The new riders, he continued, go really fast in the first part of a race because of the very high corner speed they learned on 250s, yet, “It’s better, overall, if you can also steer at the back.” He went on to say that Alex Criville shows promise of learning this.

“I can push the front-I have pushed the front. But if you keep pushing the front all the time, you’re going to make a mistake. It’s really a matter of finding a way of riding that limits the risk to yourself.

“You have to change your style as the tire changes. The last 10 laps are where it all comes together, really.”

This means that Doohan changed his style, on the fly, to suit changing conditions. Yet riders naturally resist style changes. A rider’s style is his protection, his safe route through a high-risk environment. Yet Doohan had not only been able to take in stride all the machine and tire changes of the past 10 years, but was also able as he rode to make style switches that other riders couldn’t make in a year, or even in five years.

Adaptability has been Doohan’s key to winning races; to be quickest and most accurate in responding to change.

Equally remarkable has been his ability to recover from injuries—not only physically, which has been remarkable enough, but also psychologically. When a rider crashes, there is a hole in his web of security that must be closed up by discovering the cause and eliminating it. Many riders are unable to quite reach 100 percent again after a serious crash. Doohan did it again and again.

I asked about the 1998 change to nolead fuel, which has forced compression ratios and torque to lower values. I got a characteristic trenchant Mick Doohan answer: “The ‘green’ bike is not a racing motorcycle. It’s a streetbike.”

Doohan’s now-famous technical innovation was the thumb brake (seen now on almost every Superbike in U.S. competition). He adopted it out of need, when injuries prevented his using the foot brake, then discovered other uses for it. The thumb brake can be applied at times when the foot can’t reach the pedal, and is much more sensitive. This allows the rear brake to handle work that would otherwise have to be done by the hardworked front tire.

I described seeing European riders, accelerating out of corners, make no attempt to pull their weight forward to make their bikes steer. With front ends pushing and bikes running wide, these riders then desperately try to “dig in” the front tire-to increase steer angle in hopes of making the tire respond even with almost no weight on it. This risks tucking the front end and falling.

“Riders don’t necessarily do what they do because they understand how it works,” he replied. “It’s just something they’ve come to on instinct. Ninety-five percent of riders who reach Grand Prix level have really good skills, but they don’t always have a plan for moving ahead.”

More than one top European rider is known for his unwillingness to undertake physical training to improve strength and stamina. Doohan trained mercilessly-both to make himself capable of riding at 100 percent to the very end of races, and to recover from injury. More common sense that is apparently not all that common.

When I asked him what were the milestones in his riding technique, he said, “There’s only one, really, and that would be learning to ride the 500. I learned that a 500 can’t be steered on the front wheel. I’d had a few crashes, and I could see I’d have to come up with a way to move forward or I might as well stop there.”

Doohan came up from local racing, quickly graduating to importer-team Superbikes. At some point, he realized he could win championships. Knowing that, would it make sense not to win? Not winning means you overlooked something, made avoidable mistakes, behaved stupidly. Doohan has always found a way to move forward.

How will you do without racing?

“I’ll miss it,” he replied, “But I won’t be depressed! I’m going to take 12 months to let things settle, and take care of the tail end of a racing career. I’m very fortunate-I accomplished what I set out to do. I’ve always had that in front of me, and now it’ll be behind me. Motorcycling has been important to me and it always will be.”

He then referred to the talked-about deal to manage a team for flamboyant 250cc GP star Valentino Rossi, now signed to ride a Honda NSR500 in 2000. Just days after our interview he announced officially that he took the deal as general manager.

“I’m 35 years old-I will be this year. I’m not an old man, but I’m old for my sport. I know the next 15 years will go quickly, and then I’ll be 50. Another 30 and I’ll be 80, and that about sums it up,” Doohan said.

He wasn’t referring to the shortness of life but to the value of time. He has a family now, and time in which to expand from racing’s narrow discipline.

“It seems strange-the last time I rode a motorcycle was last May. If > everything were as it used to be, I ought to be going to the first test right about now.

“I’ve had time to read, so I’ve completed the written part of the pilot’s exam.” That explained the aviation magazines on the kitchen table and in his car. The 1977 500cc world champion, Barry Sheene, lives only 2 miles away, and has kept up his helicopter rating. Daryl Beattie, another retired GP racer and fellow Queenslander, flies a 1940s Beech Staggerwing and an aerobatic Sukhoi.

As Doohan walked to the door to drive me back to my hotel, his difficult movement suggested the extent of his accumulated injuries. How, I wondered, could this body be the source of all the powerful, violent grace we have seen in his riding? Of course, it is not. The grace comes from his mind.