INDIAN HISTORY

IGNITION

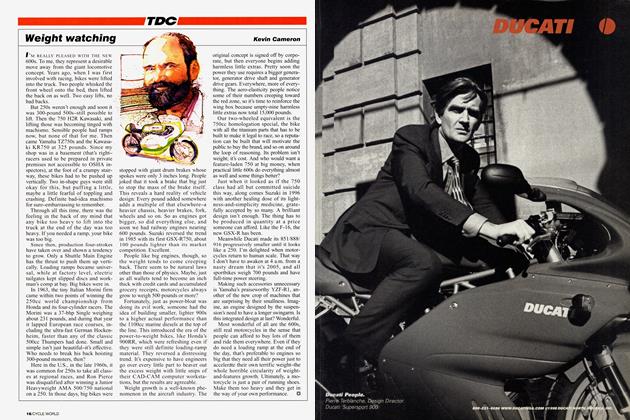

TDC

BIG IMPACT FROM SURPRISINGLY SMALL NUMBERS

KEVIN CAMERON

So much history was created by so few Indian motorcycles, in a sport that was then such a tiny part of the American scene. In its greatest years, Indian was a major innovator, pioneering all-chain drive and a two-speed transmission at a time when belt drive and “light pedal assist” were so common that Isle of Man TT race authorities banned pedaling in 1911. In that year, advanced Indians swept the TT, 1-2-3. Because motorcycles are the cheapest basic transportation, those early years were a golden age for Indian, peaking in 1913 with 31,900 machines produced.

Putting that in perspective, Indian in round figures produced a total of 400,000 machines from its beginning in 1901 to its end in 1953—a number that Honda in 2014 produced every eight and a half days. In 1929, in the prosperity that immediately preceded the Great Depression, there was one motorcycle registration in the US for every 800 Americans. Four years later, in the depths of the depression, when Indian produced only 1,657 machines, there was one registration for every 1,300 Americans. Japanese motorcycles barely existed, and none was imported here. There was no Ducati and no KTM. There had been 200 American motorcycle producers, but manufacturing economics or the depression killed almost every one of them.

In 2014, there was one motorcycle registration for every 37 Americans.

Indian continued to be a technology leader, demonstrating first with the Powerplus of 1916 and then in the evolving Scout line the value of rapid squish-assisted combustion. Franklin’s Irish-born racer-engineer Charles B. Franklin had independently discovered that causing part of the piston to closely approach the head at TDC “squished out” a fast-moving jet of mixture that accelerated combustion in the main chamber. Such rapid combustion burned up the

charge before heat effects could lead to combustion knock—detonation. This allowed side-valve engines to run safely on compression ratios that gave good pulling power.

Much romantic admiration is lavished upon the eight-valve OHV racers built by both Indian and Harley, but their fastwearing exposed valve gear and inability to pull from lower revs without knock kept them from non-track use. Franklin’s flatheads were production-practical because their entire valve trains were light in weight, fully enclosed, and lubricated, and their fast combustion gave them the ability to accelerate from low revs.

In a business sense, Indian did more things wrong than right, but the quality of the machines and their technology forged a lasting reputation. Between the wars, 1919 to 1939, Indian and Harley exported one-quarter to one-third of their production. In 1920, an obscure New Zealander named Burt Munro bought one of Franklin’s new Scout models, and we all know where that led. Many a famous European auto or motorcycle racer got his start on an Indian. In the 1920s, as British makers were switching from side valve to OHV, Franklin too produced advanced OHV single-cylinder prototypes—but the company could never get far enough ahead financially to try them in the market. Harley, more practical and less flashy, attended to the basics and survived. It would be Harley, not Indian, who would first bring an American OHV machine to quantity production—its EL of 1937.

Encouraged by its early sales success, Indian constructed a giant brick plant in Springfield, Massachusetts, with a notional capacity to build 35,000 bikes a year. But in 1913 Ford’s Model T hit the market, quickly satisfying the demand for cheap basic transportation. Indian sales declined. Ford’s innovation was rational mass production, which cut costs to the bone—especially when com-

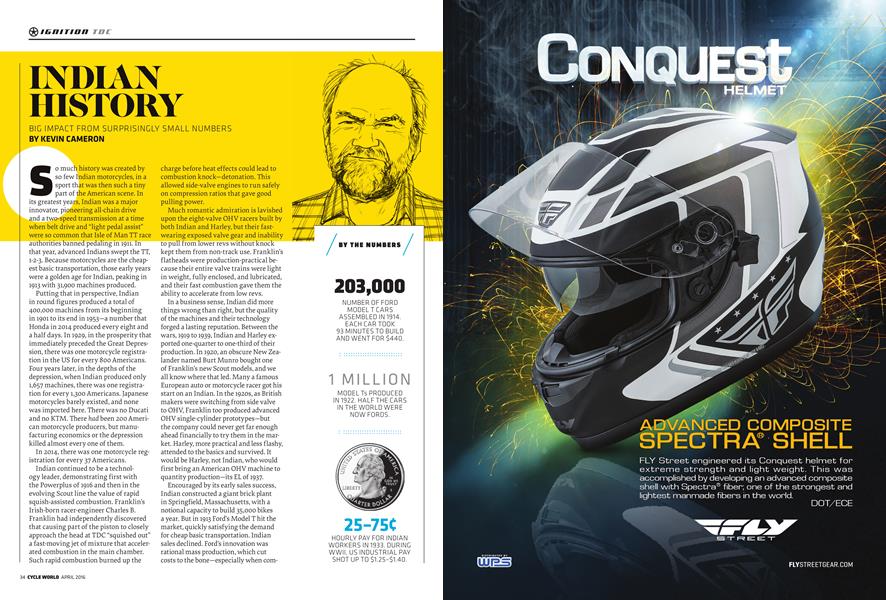

BY THE NUMBERS

203,000

NUMBER OF FORD MODELTCARS ASSEMBLED IN 1914.

EACH CAR TOOK 93 MINUTES TO BUILD AND WENT FOR $440.

1 MILLION

MODELTs PRODUCED IN 1922. HALFTHE CARS INTHE WORLD WERE NOW FORDS.

25-75C HOURLY PAY FOR INDIAN WORKERS IN 1933. DURING WWII, US INDUSTRIAL PAY SHOTUPTO $1.25—$1.40.

pared to the modified craftsman methods still being used in the motorcycle business. Ford could cut costs by such means as plunge grinding of crankshaft journals on new high-production machines, while Indian and Harley continued to make their cranks from five pieces—two taper-and-nut mainshafts, two shaped flywheel-cumcounterweight discs, and a single taper-and-nut crankpin. In a time when a V-twin motorcycle cost $285 the bike makers could only look on in amazement as the price of a Model-T Ford plummeted with every production enhancement.

When World War I ended, there was a post-war inflation (governments pay for wars by printing money), pushing up materials prices and wages. A big reorganization momentarily reversed Indian’s splash into red ink, and the popularity of the Powerplusderived Scout and its big brother the Chief expanded, which

brought a few good sales years.

Then came the Great Depression, which led to irrational acts, such as selling off the Scout tooling. And with Europe heading for war, here came foreign orders for all the essentials—motorcycles among them. Indian again produced thousands of military motorcycles but failed to read the contract fine print, losing money on wartime parts production.

Then came a decision that looked timely—to widen the motorcycle market by producing lighter sporting machines. It would work for Britain in the post-WWII years, but Indian’s new parallel twins failed from reliability problems.

Yet despite this, demand existed for the Scout. A strong visual feature of Indian’s flathead V-twins was their exhaust header pipes, which pointed nearly straight down from the ports. This was an advanced feature, for if we mentally invert those side-mounted

exhaust valves and ports to new positions atop the cylinders as overhead valves, their up-flowing ports suddenly look very modern, like those of Ducati’s Testastretta. Experience had taught C.B. Franklin the value of big valves and high-flowing ports—not only for good performance but also to minimize the inherent problem of side-valve engines; cylinders are distorted by the close proximity of hot exhaust ports, possibly leading to leakage, lubrication failure, and in extreme cases to seizure. Scout and Chief exhaust ports were surrounded by big cooling fin area. A free-flowing exhaust is another great aid to keeping an air-cooled engine reliable because it gets the hot stuff out quickly.

The temptation in looking at these 8o-year-old engines is to see only quaintness, but in fact every engine design is a well-considered response to the big problems of the moment. E1MM

...IN 1913 FORD’S MODELT HITTHE MARKET, QUICKLY SATISFYING THE DEMAND FOR CHEAP BASIC TRANSPORTATION. INDIAN SALES DECLINED.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue