Legal tender

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

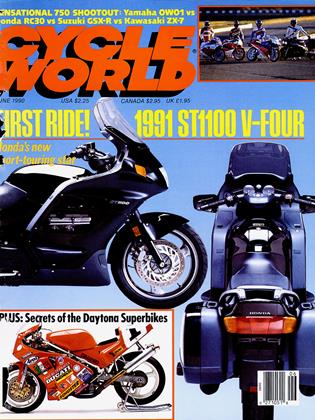

"YOU GOING TO THE AUCTION?" ALlan Girdler asked, poking his head into my office.

“Probably," I said. “What auction?"

He handed me a flyer that said. "Los Angeles Vintage & Classic Motorcycle Auction. Santa Monica Civic Auditorium." Below the large type were separate photos of 60-some bikes to be sold. An interesting mixture of stuff, mostly Harleys and British, with a smattering of Italian and Japanese iron, some early Indians and Hendersons, with a few skeletal remains of pre-WWI bikes that looked like they might have been dredged up from river bottoms. One photo showed a wooden crate, above the legend. "1963 BSA Goldstar DBD-34—new in crate."

“Sounds good to me," I said, my eyes magnetically drawn to any number of clean-looking Norton Commandos and 1960s Triumphs, not to mention a Series C Vincent Rapide and a nice Velocette Venom. “I don’t have enough money to buy anything," I told Allan, “but I can easily imagine worse ways to spend a Saturday than looking at all these bikes. Besides. I’ve never been to a motorcycle auction before."

Editor David Edwards and my friend John Jaeger decided to go. too, so we all met at my house at 7:30 in the morning. Allan threw' up his best defense by arriving on his Harley and announcing that he’d left both his money and pickup truck at home, making an accidental purchase nearly impossible. Edwards was out for blood, however—pickup truck, large wad of cash and that strange blue light you see in the eyes of individuals who have decided that what they really need in life isa 1975 Triumph T-Í60 Trident, as pictured in the auction brochure. There were even tie-downs in the truck, coiled like grappling hooks. Big trouble. Those who plan for the worst, as Walter Miller once said, will soon have it.

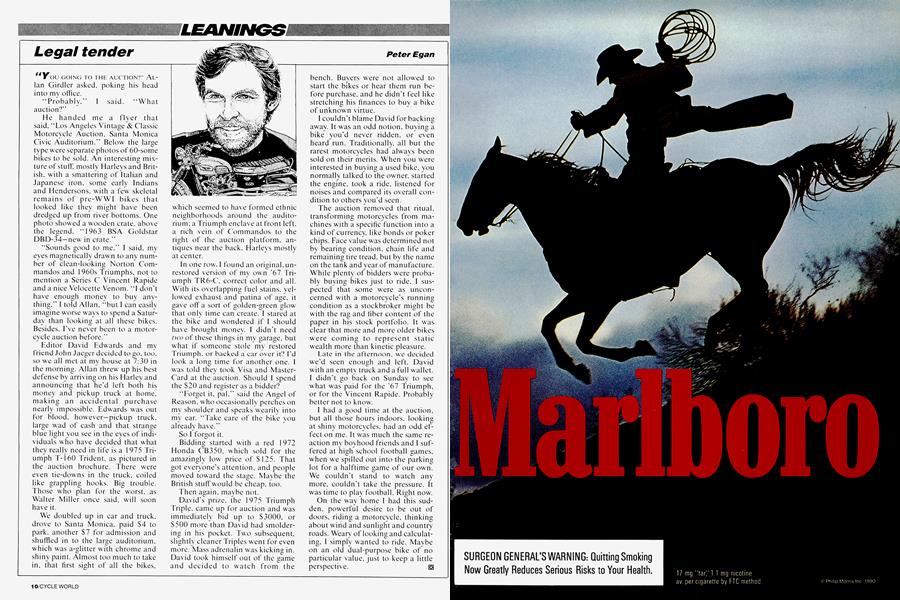

We doubled up in car and truck, drove to Santa Monica, paid S4 to park, another $7 for admission and shuffled in to the large auditorium, which was a-glitter with chrome and shiny paint. Almost too much to take in, that first sight of all the bikes. which seemed to have formed ethnic neighborhoods around the auditorium; a Triumph enclave at front left, a rich vein of Commandos to the right of the auction platform, antiques near the back. Harleys mostly at center.

In one row, I found an original, unrestored version of my own '67 Triumph TR6-C. correct color and all. With its overlapping fuel stains, yellowed exhaust and patina of age, it save off'a sort of golden-green glow' that only time can create. I stared at the bike and wondered if I should have brought money. I didn't need two of these things in my garage, but what if someone stole my restored Triumph, or backed a car over it? I’d look a long time for another one. I was told they took Visa and MasterCard at the auction. Should I spend the $20 and register as a bidder?

“Forget it, pal.” said the Angel of Reason, who occasionally perches on my shoulder and speaks wearily into my ear. “Take care of the bike you already have.”

So I forgot it.

Bidding started with a red 1972 Honda CB350. which sold for the amazingly low price of $125. That got everyone's attention, and people moved toward the stage. Maybe the British stuff'would be cheap, too.

Then again, maybe not.

David's prize, the 1975 Triumph Triple, came up for auction and was immediately bid up to $3000, or $500 more than David had smoldering in his pocket. Two subsequent, slightly cleaner Triples went for even more. Mass adrenalin was kicking in. David took himself out of the game and decided to watch from the

bench. Buyers were not allowed to start the bikes or hear them run before purchase, and he didn’t feel like stretching his finances to buy a bike of unknow n virtue.

I couldn’t blame David for backing aw'ay. It was an odd notion, buying a bike you'd never ridden, or even heard run. Traditionally, all but the rarest motorcvcles had alw'avs been

J J

sold on their merits. When you were interested in buying a used bike, you normally talked to the owner, started the engine, took a ride, listened for noises and compared its overall condition to others you’d seen.

The auction removed that ritual, transforming motorcycles from machines with a specific function into a kind of currency, like bonds or poker chips. Face value was determined not by bearing condition, chain life and remaining tire tread, but by the name on the tank and year of manufacture. While plenty of bidders were probably buying bikes just to ride. I suspected that some were as unconcerned with a motorcycle's running condition as a stockbroker might be with the rag and fiber content of the paper in his stock portfolio. It w'as clear that more and more older bikes were coming to represent static wealth more than kinetic pleasure.

Late in the afternoon, we decided we’d seen enough and left. David with an empty truck and a full wallet. I didn't go back on Sunday to see what was paid for the '67 Triumph, or for the Vincent Rapide. Probably better not to know?

I had a good time at the auction, but all those hours indoors, looking at shiny motorcycles, had an odd effect on me. It was much the same reaction my boyhood friends and I suffered at high school football games, when we spilled out into the parking lot for a halftime game of our own. We couldn't stand to watch any more, couldn't take the pressure. It w'as time to play football. Right now.

On the way home I had this sudden. powerful desire to be out of doors, riding a motorcycle, thinking about wind and sunlight and country roads. Weary of looking and calculating, I simply wanted to ride. Maybe on an old dual-purpose bike of no particular value, just to keep a little perspective.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontConversations

June 1990 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeThe Sport of the '90s

June 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupBrm Spyder Upgrading the Gsx-R1 100's Flash Factor

June 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

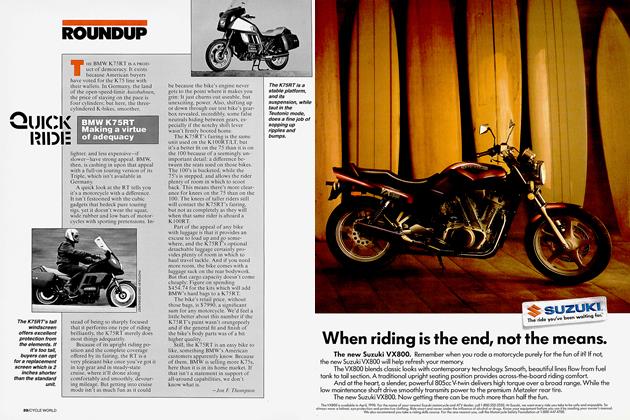

RoundupBmw K75rt Making A Virtue of Adequacy

June 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupJune, 1965

June 1990