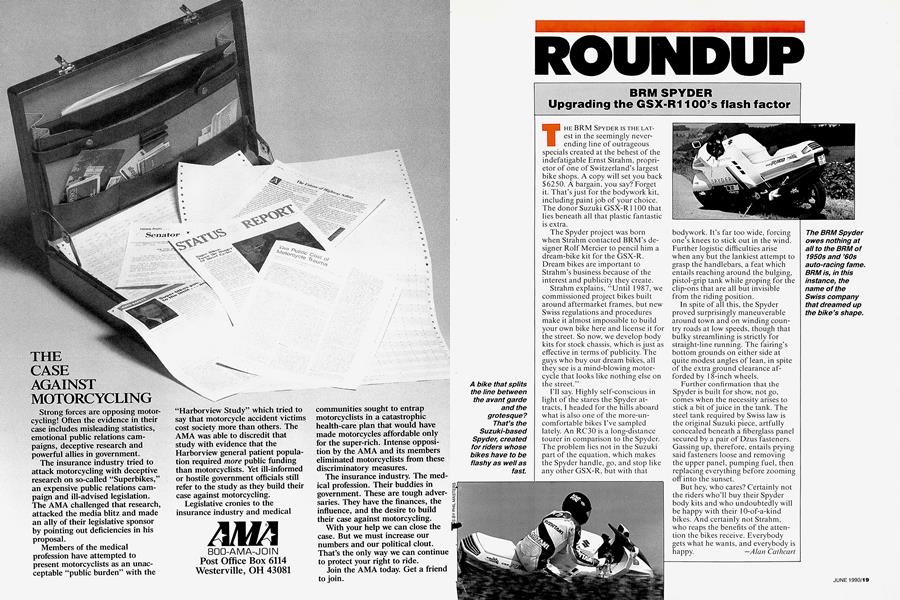

BRM SPYDER Upgrading the GSX-R1 100's flash factor

ROUNDUP

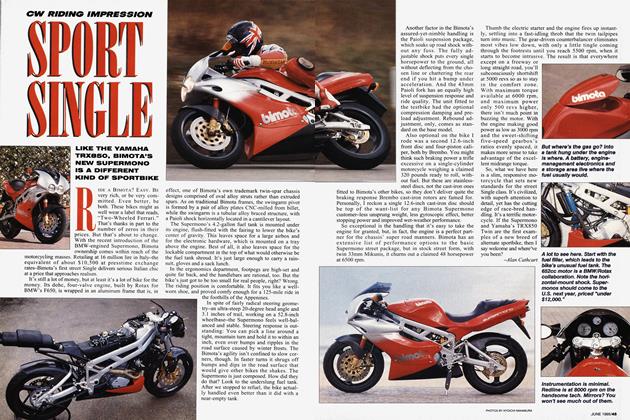

THE BRM SPYDER IS THE LATest in the seemingly neverending line of outrageous specials created at the behest of the indefatigable Ernst Strahm, proprietor of one of Switzerland's largest bike shops. A copy will set you back $6250. A bargain, you say? Forget it. That's just for the bodywork kit, including paint job of your choice. The donor Suzuki GSX-R1100 that lies beneath all that plastic fantastic is extra.

The Spyder project was born when Strahm contacted BRM’s designer Rolf Mercier to pencil him a dream-bike kit for the GSX-R. Dream bikes are important to Strahm’s business because of the interest and publicity they create.

Strahm explains, “Until 1987, we commissioned project bikes built around aftermarket frames, but new Swiss regulations and procedures make it almost impossible to build your own bike here and license it for the street. So now, we develop body kits for stock chassis, which is just as effective in terms of publicity. The guys who buy our dream bikes, all they see is a mind-blowing motorcycle that looks like nothing else on the street.’’

I’ll say. Highly self-conscious in light of the stares the Spyder attracts, I headed for the hills aboard what is also one of the more-uncomfortable bikes I’ve sampled lately. An RC30 is a long-distance tourer in comparison to the Spyder. The problem lies not in the Suzuki part of the equation, which makes the Spyder handle, go, and stop like any other GSX-R, but with that bodywork. It's far too wide, forcing one's knees to stick out in the wind. Further logistic difficulties arise when any but the lankiest attempt to grasp the handlebars, a feat which entails reaching around the bulging, pistol-grip tank while groping for the clip-ons that are all but invisible from the riding position.

In spite of all this, the Spyder proved surprisingly maneuverable around town and on winding coun try roads at low speeds, though that bulky streamlining is strictly for straight-line running. The fairing's bottom grounds on either side at quite modest angles of lean, in spite of the extra ground clearance af forded by 18-inch wheels.

Further confirmation that the Spyder is built for show, not go, comes when the necessity arises to stick a bit ofjuice in the tank. The steel tank required by Swiss law is the original Suzuki piece, artfully concealed beneath a fiberglass panel secured by a pair of Dzus fasteners. Gassing up, therefore, entails prying said fasteners loose and removing the upper panel, pumping fuel, then replacing everything before zooming off into the sunset.

But hey, who cares? Certainly not the riders who'll buy their Spyder body kits and who undoubtedly will be happy with their 10-of-a-kind bikes. And certainly not Strahm, who reaps the benefits of the atten tion the bikes receive. Everybody gets what he wants, and everybody is happy. —Alan Cathcart

View Full Issue

View Full Issue