MOKO HARLEYDAVIDSON

ALAN CATHCART

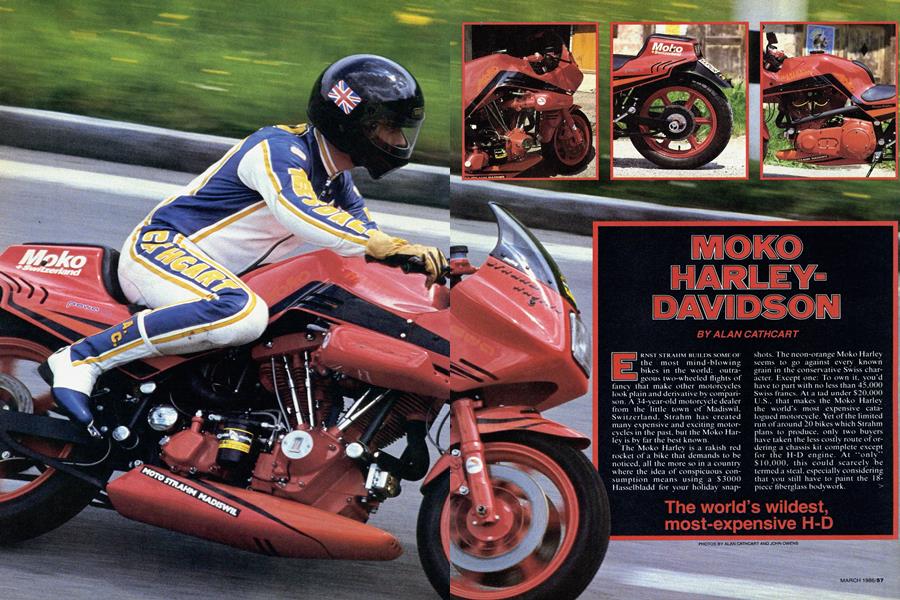

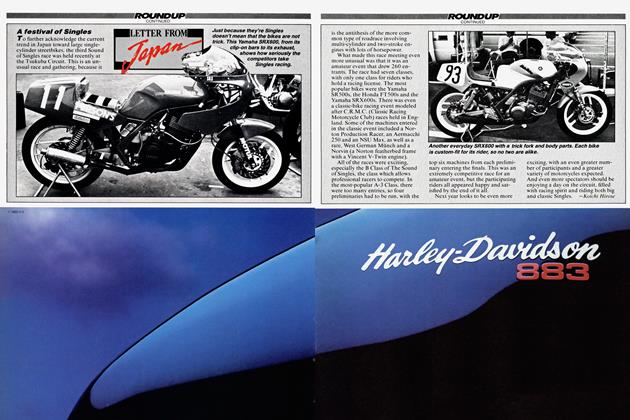

ERNST STRAHM BUILDS SOME OF the most mind-blowing bikes in the world: outrageous two-wheeled flights of fancy that make other motorcycles look plain and derivative by comparison. A 34-year-old motorcycle dealer from the little town of Madiswil. Switzerland. Strahm has created many expensive and exciting motorcycles in the past, but the Moko Harley is by far the best known.

The Moko Harley is a rakish red rocket of a bike that demands to be noticed, all the more so in a country where the idea of conspicuous consumption means using a $3000 Hasselbladd for your holiday snap-

shots. The neon-orange Moko Harley seems to go against every known grain in the conservative Swiss character. Except one: To own it. you'd have to part with no less than 45,000 Swiss francs. At a tad under $20.000 U.S.. that makes the Moko Harley the world's most expensive catalogued motorcycle. Yet of the limited run of around 20 bikes which Strahm plans to produce, only two buyers have taken the less costly route of ordering a chassis kit complete except for the H-D engine. At “only” $10.000. this could scarcely be termed a steal, especially considering that you still have to paint the 18piece fiberglass bodywork. > If possible, the Moko Harley looks even more outrageous in the flesh than in print. After all the hype and overkill styling, it comes as almost a surprise that the bike can actually be ridden at all. The base of the beauty is a 1973 iron-barreled FLH Harley engine, in standard 1340cc form (though any 80 eu. in. H-D unit can be used, even the latest Evolution alloy design). Strahm bemoans his

The world's wi1dest~ most-expensive H-D

greatest problem in meeting the desires of those high-rollers who’ve put down a deposit for a machine: the lack of suitable donor Harleys from which he can take the engine and gearbox. “There aren’t many Harleys in Switzerland anyway,” he says, “and those that are tend to be ridden so slowly they never crash or wear out. We have to go to Germany to buy engines from the U.S. air bases, but even there, people usually do anything they can to keep their bike on the road rather than sell it.”

What your average American Harley rider—if there is such a person — would make of the Moko H-D is hard to fathom. For one thing, there is none of the traditional Harley massiveness to this bike. It feels very small when you first swing a leg over it, even though the 58.7-inch wheelbase is rather long. Furthermore, the seating position is strange because the footrests are set very far rearward so they can be tucked in behind the engine’s enormous primary case, to offer increased ground clearance. Then there’s the big, 7.6-gallon steel fuel tank, shrouded by a shapely fiberglass cover that fits snugly against your chest.

Once seated on the wide-based saddle, you then have to grapple with the ignition key, mounted in traditional H-D fashion on the left, between the cylinders. Turning the key

sets the high-pressure fuel pump ticking; thumb the starter, and after a couple of desultory grunts the beast thunders into life. And in true, oldtime Harley fashion, your world is suddenly multiplied by at least two as the massive vibration of the 45-degree V-Twin engine makes itself felt.

Thanks to the engine’s prodigious torque, the bottom two gears are pretty well redundant on a sportbike like this. The comprehensive dashboard, lifted directly from a Fiat car, does boast a tachometer, but it’s irrelevant to your rate of progress. Simply change up when the 40mm twinchoke Dell’Orto carburetor—lifted from an Alfa Romeo parts bin—runs out of breath. The engine allegedly peaks at 5500 rpm, but with power from zero rpm, once you get into top gear you can pretty well leave it there. If you want a slightly spicier rate of acceleration, you can drop down a gear to third if you insist, but it’s hardly worth the effort. Simply whuff-whuff along all day in top gear until you have to come to a halt.

All of this is perfectly commonplace for anyone used to riding a big Harley, but theMoko should considerably expand such a person’s horizons by the way in which it matches such effortless torque to a modern, quickhandling chassis. Strahm’s friend Hausi Hilti, head of the Moko framebuilding company, is responsible for bending the tubes that tie the Harley together. The engine is suspended from a tubular chrome-moly steel backbone, four inches in diameter, which also doubles as an oil tank for the dry-sump engine. The steeringhead angle is a fashionably steep 25.5 degrees, which, combined with the 16-inch front wheel and 4.25-inch trail, gives quick handling in tight corners. This causes no problems, though at first you get a feeling of instability that lessens as you get used to the bike’s idiosyncrasies.

The monoshock rear suspension employs a DeCarbon unit mounted horizontally under the gearbox, with 4.7 inches of travel via a system of rods and linkages. Hilti describes the setup as “linear, but a little bit progressive.” Up front, a 42mm Forcella Italia fork has 5.7 inches of travel, a preload adjustment on the top of the stanchions, and includes a hefty steel brace from which the front mudguard is suspended.

But you don’t want to be fooled by the good handling and smooth suspension into going too fast; the Moko Harley displays all the hallowed braking characteristics of its older American cousins—i.e. you have to squeezelikehell to stop and hope you started planning soon enough. This is most surprising, because the Moko is nicely endowed with twin 1 1.8-inch Brembo front discs and calipers. Of

course, at 531 pounds dry, the Moko is a pretty hefty lump (the engine alone weighs 238 pounds). Fortunately, the 10.2-inch disc and Lockheed caliper on the rear offer excellent stopping capabilities.

Similarly hard to work is the clutch, which has extremely stiff lever action and further discourages use of the gearbox; the hard pull makes the shift from first to second extremely difficult. The shifting in general is very notchy and requires you to hold the clutch in for what seems like an eternity before the cogs engage.

But when all is said and done, what really matters on this bike above all else is the styling; there’s no disputing that Strahm has produced an absolutely outrageous bike to look at. The concept of combining a good, easy-handling chassis with a lazy, lusty engine from another place and time has been tried before, but never has the result been so stunning.

Still, the question remains: Why would anyone build such an exotic machine around an engine that, even by the manufacturer’s implicit admission, is outdated? “I wanted to build something nobody else had,” says Strahm. “I’d have preferred to make a Ducati, but there are any number of modern chassis for the big Desmo, and nobody had done a Harley, especially not quite like this. I really

wanted to make an XR 1000 version, and I actually have a chassis all ready; but can’t get hold of an engine. There just aren’t any in Europe. Anyway, this bike has done everything I could have wanted of it. It’s really focused attention all over the world on what I’m doing.”

With a bike as radical as the Moko Harley, that just might be the understatement of the year. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue