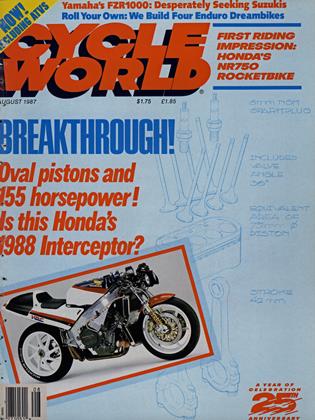

HONDA NR750

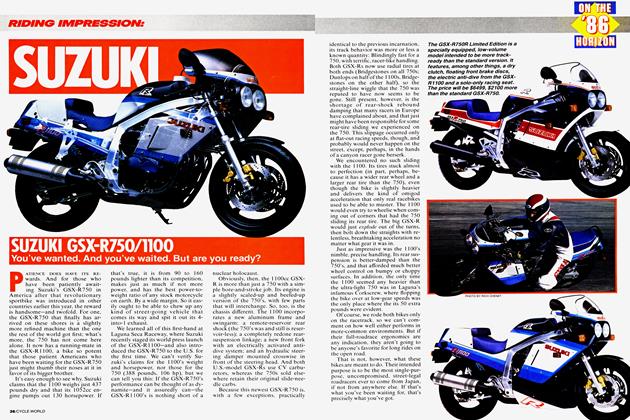

RIDING IMPRESSION

How do you pet a 155-horsepower pussycat? Carefully, very carefully.

ALAN CATHCART

SOMETIMES, DREAMS DO COME TRUE. Easter at the Paul Ricard racetrack in France for a two-day vintage race meet. After an earlymorning practice session, I was just sitting down to a breakfast of croissants and coffee in the Provencal sunshine when the public-address system blasted into life. Even above the thunder of assorted Golden Oldies returning from the track, I heard the announcement: “Will Alan Cathcart please come to race control; there is a message for him.”

It meant letting my coffee go cold, but you never know what these things might be, so I duly fronted up to the track office, to find a phone call awaiting me from Honda France. “Hello, I'm calling from Le Mans where the 24hour race will start later today. I'm glad we finally tracked you down, but it appears you're in the right place: How would you like to test-ride our new oval-piston NR750 prototype at Rieard on Monday, as well as this year’s RVF750 endurance racer? We’re going to drive through the night on Sunday so as to be there first thing in the morning the day after the race ends. Can you make it?”

You won't often find me lost for words, but there are exceptions to every rule. And anyway, I was trying to figure out which of my friends was bold enough to stage what was obviously a gigantic and well-executed leg-pull. It had to be someone who knew how fascinated I’ve been for the past decade with the whole NR500 oval-piston project, and how hard I’ve tried to persuade Takeo Fukui, boss of HRC, to let me ride the apparently aborted prototype GP bike.

“Don’t worry,” said Philippe Boursereau, public-relations chief of Honda France, apparently reading my thoughts by long distance. “This isn’t a joke. I assure you we’ll be there, and we hope very much you will be, too. Just a select six or eight journalists to ride the two bikes and talk to Honda technicians about it. Mr. Fukui and Mr. Oguma of HRC especially asked if you could come.”

Mentally reminding myself of the debt of gratitude I now owed the two top men in HRC, I wandered back to the paddock in a daze. I can’t really say I gave the weekend’s racing my best shot after that—had to stay in one piece for the Honda test, you know.

Come Monday morning, the Honda boys were indeed at Paul Ricard, rolling out the RVF750, which we would ride before saddling up to the NR. Honda’s confidence in the conventional V-Four was amazing. Just the day before, this machine had been flogged for almost 2000 miles en route to a win at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, yet here it was, ready for our inspection with nothing more than an oil change and a new set of brake pads.

A thumbnail sketch of the RVF? Well, certainly this a sharper-edged sword than the bike’s 1986 predecessor. Whereas that bike had a mile-wide powerband, acres of torque and seemed like a superfast roadbike, the 1987 version feels much more like a genuine GP bike, with an altogether peakier, more highly strung engine which demands active use of a new, six-speed gearbox. The new bike is, frankly, less enjoyable to ride, but it is much more effective, resembling nothing as much as a four-stroke 750cc Grand Prix racer, in recognition of the ever-increasing pace of endurance competition.

Still, our laps at the controls of the RVF were merely a prelude to the real reason for this Paul Ricard press session: to gain exposure for the NR750 and its oddly shaped pistons. The bike’s appearance at Le Mans in the hands of Aussie ace Mai Campbell and journalists Ken Nemoto (of RIDERS CLUB, Japan) and Gilbert Roy (MOTO REVUE, France) was itself a PR coup designed to draw maximum attention to the fact that all those promises made long ago about oval-piston technology were more than just hollow breast-beating on Honda’s part. The much-maligned NR500, albeit in an altered form, had returned in the NR750. And how.

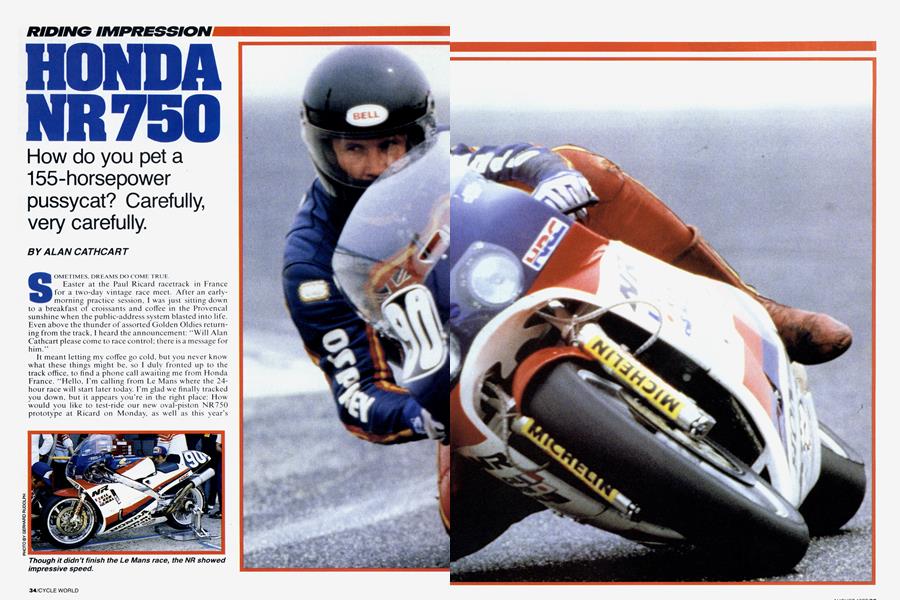

Second-fastest in practice by a whisker behind the works RVF, the NR750 stunned its competition and spectators alike with its devastating turn of speed: Literally nothing on the track could stay with it. Though its retirement with engine trouble after three hours must have been a bitter disappointment to Honda, here it was awaiting me at Paul Ricard, fitted with a fresh engine, all ready to go.

It was a good move to let us sample the RVF first, because it helped to put the NR750’s performance in perspective in no uncertain fashion. Just when you think you’ve ridden a paragon amongst racing four-strokes, along comes the real McCoy to knock it off its perch. Often, when you finally come to grips with something—or someone—you’ve been lusting after for ages, disappointment results; reality fails to fulfill expectation. But riding the NR was everything you and I might have expected it to be: a phenomenal experience. All I can say after a dozen all-too-short laps aboard the NR750 is wow!

It’s safe to say that this motorcycle could not have been built before the advent of radial tires, because the horsepower is such that you can slide the rear wheel in every corner if you’ve a mind to, simply by opening the throttle injudiciously. Crack the light-action twistgrip open exiting a bend while cranked over, and as the eight carburetor butterflies open, the front wheel lifts, the bars shake lazily in your hand, and suddenly the rev counter is reading 15,500 rpm—and it’s time to change gears now.

The NR750 engine isn’t as smooth as the conventional V-Four, perhaps because of the slightly narrower angle of its V-spread, but it’s even more flexible. Power comes in at 6500 rpm, followed by a strong pull at 8000 revs and a belt in the back once you get to the five-figure area where the engine likes to operate: It smooths out completely above 10,000 rpm. The left-foot, one-up, five-down gearchange is slightly harsh and notchy but quite positive, its six ratios well-chosen to keep the engine churning up in the 1 1,000to-14,000-rpm area where it seems to produce the most power.

But honestly, you must take great care in how you ride the bike, because it is just so powerful, so potent. Also, while you’re riding this bike you can’t forget what it represents in terms of development yen and man-hours; and this, combined with the sheer power available, induces a healthy concern for self-preservation. You must ride the NR with a delicacy that matches the lightness of its controls; but if you do it right, you’re repaid by the most scintillating performance you’ve ever experienced from a four-stroke motorcycle. In the end, you stop being overawed because the sheer delight of having all that smoothly delivered horsepower on tap is so pleasurable.

Of course, a superlative engine in an ordinary chassis wouldn’t do, but the NR’s twin-spar frame is up to the task. At casual glance, it is a clone of the RVF’s frame, but subtly, it is vitally different when you come to ride it. Thanks largely to the NR’s more-compact engine, the riding position is definitely lower, and you feel more comfortable and more a part of the bike than on the ’87 RVF. The NR also feels lighter and easier to change direction on, especially through Ricard’s famous “Pif-Paf” S-turns. Presumably, this is because the center of gravity is lower and/or the polar moment of inertia has been reduced by close attention to compacting the center of mass. Thanks to the effective grip of the Michelin radiais, the NR is easy to bank over hard, or to flip quickly from one side to the other, provided you take care not to get over-exuberant with the throttle on the way out; even radiais have their limits. And unlike the RVF, the NR is much more neutral under braking when cranked over. It’s an easy bike to ride hard—if you don’t forget the immense reserves of power.

And it is horsepower that will become this motorcycle’s calling card. By harnessing the NR’s considerable potential in such a usable way, Honda has made the real breakthrough. But it isn't just Honda’s ability to make oval pistons work that you have to admire; it’s how the power those pistons have unleashed is delivered and managed that is truly impressive. And there seems to be more ovalpiston advances waiting in the wings.

“Which one did you ride?” asked Honda’s GP-man Wayne Gardner when I saw him later that week at the Spanish GP and mentioned that I’d tested the NR750. “Oh, the endurance bike, with about 150-160 horsepower? Yeah, that one’s just a pussycat,” he said. “They can get 200 horsepower from the NR once they really start trying with the oval-piston idea. Honda can do anything they put their minds to, if they decide it's important enough, especially with four-strokes.”

Words of a loyal HRC servant, maybe. But after riding the endurance version of the NR750, designed to run for 24 hours at racing speeds, I'm beginning to think he’s right. An out-and-out sprint-race NR, either in Superbike or GP trappings, is something to contemplate. Who knows what improvements can—and will—be wrought on this most impressive of beginnings?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialSummer of '47

August 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1987 -

Departments

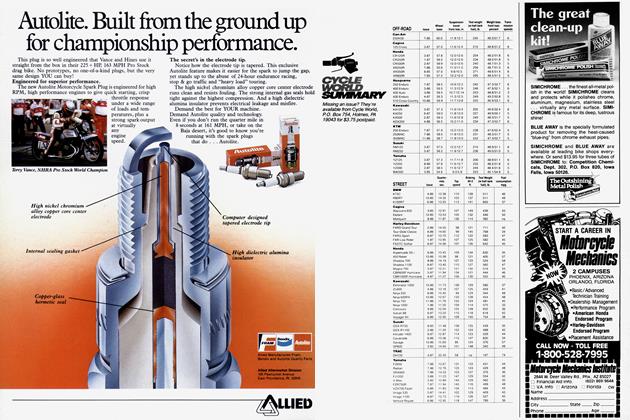

DepartmentsSummary

August 1987 -

Roundup

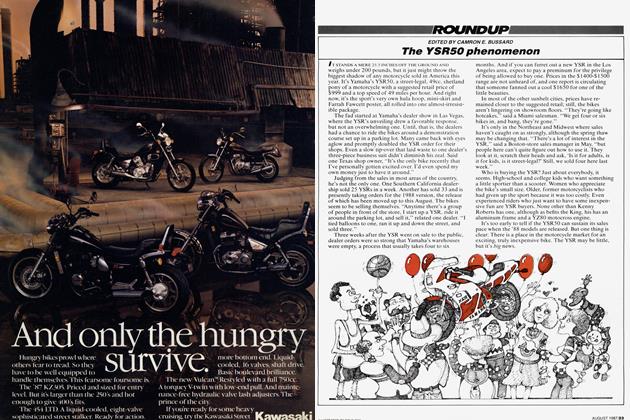

RoundupThe Ysr50 Phenomenon

August 1987 By Ron Griewe -

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the Performance of the 400s And Into the Price of the 750s

August 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupVelocettes Live Again

August 1987