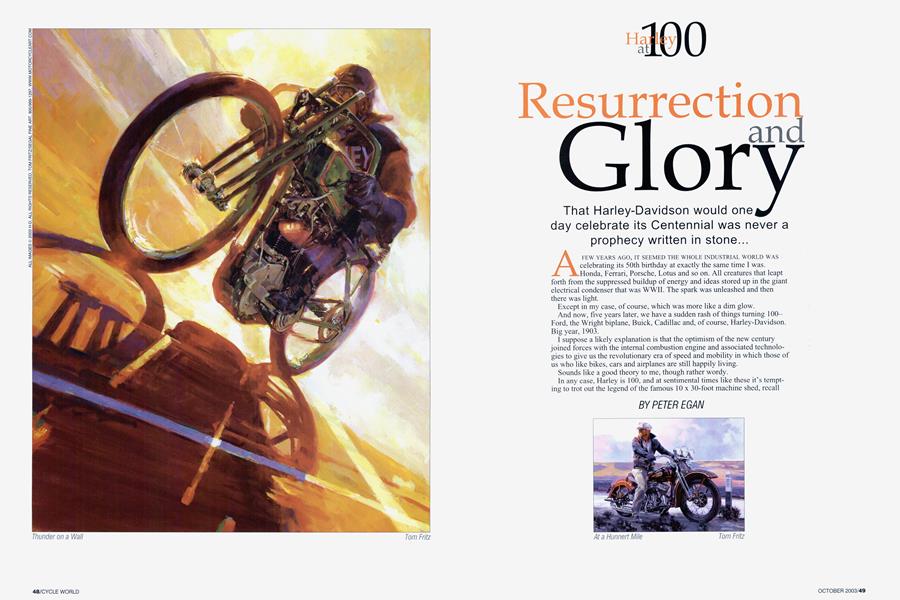

3ALL IMAGES © 2003 H-D. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. TOM FRITZ/SEGAL FINE ART. 800/999-1297. WWW.MOTORCYCLEART.COM

Resurrection and Glory

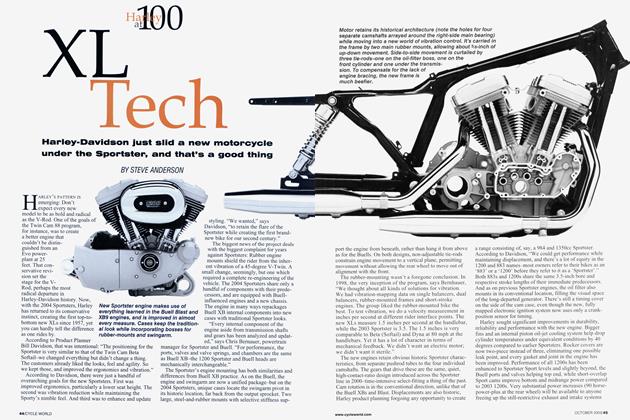

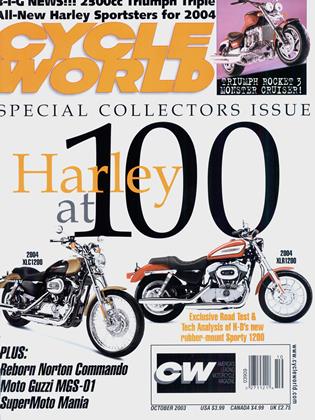

Harley at 100

That Harley-Davidson would one day celebrate its Centennial was never a prophecy written in stone...

A FEW YEARS AGO. IT SEEMED THE WHOLE INDUSTRIAL WORLD WAS celebrating its 50th birthday at exactly the same time I was. Honda, Ferrari, Porsche, Lotus and so on. All creatures that leapt

forth from the suppressed buildup of energy and ideas stored up in the giant electrical condenser that was WWII. The spark was unleashed and then there was light.

Except in my case, of course, which was more like a dim glow.

And now, five years later, we have a sudden rash of things turning 100-Ford, the Wright biplane, Buick, Cadillac and, of course, Harley-Davidson.

Big year, 1903.

I suppose a likely explanation is that the optimism of the new century joined forces with the internal combustion engine and associated technologies to give us the revolutionary era of speed and mobility in which those of us who like bikes, cars and airplanes are still happily living.

Sounds like a good theory to me, though rather wordy.

In any case, Harley is 100, and at sentimental times like these it’s tempting to trot out the legend of the famous 10 x 30-foot machine shed, recall

PETER EGAN

HOTOS © DANNY LYON/MAGNUM PHOTOS, FROM "THE BIKERIDERS' EXHIBIT MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM `TIL SEPTEMBER 14, 2003

fondly the Silent Grey Fellow and relive those glorious days of boardtrack racing, the old Indian rivalry and so on.

But to those of us who are (ahem) a little younger and still able to fog a mirror during our latest physical exam, I think a look at the past few decades may be more germane to our lives than those early, sepia-toned images. If we are to celebrate, it might be a good time to reflect, happily, that history sometimes turns out far better than we

had hoped.

Let me explain:

When I came to work for Cycle World in 198Ö, no one on the staff would have bet a large sum of money that Harley-Davidson would be alive 23 years later to celebrate much of anything. Nor would anyone have predicted that 2003 would find The Motor Company enjoying record motorcycle sales, or that hundreds of thousands of faithful owners of future bikes would come sweeping into Milwaukee for a huge party.

The general consensus in those days-among we youthful sages who thought we had a perfect understanding of nearly everything-was that Harley would be lucky to hang on for five or six more years before it joined Indian or Henderson as a quaint and charming name from the American industrial past.

In defense of our possibly overcooked pessimism, there was much precedent then for big, famous firms disappearing almost overnight, steamrollered into the pavement by the mighty Japanese industrial juggernaut with its knockout combination of quality, finish, technology and low price. The great firms of Triumph, BSA and Norton had just recently dwindled into nothingness with

remarkable swiftness, and even the American car industry was in trouble. Perhaps Harley would survive to a wistful 85th, but certainly not to a glorious 100th.

Why this sense of gloom and doom?

Well, the bikes were seen as being behind the curve, in both engineering and build quality, at a time when everything around them (save the Britbikes) was improving by leaps and bounds.

Okay, some of the AMF-era bikes were

better than others-and I think their shortcomings are often overstated in recollection (my 1977 XLCR was a very reliable bike)-but the fact remains that quality control was spotty.

Even those who loved Harleys and lusted after them were often left shaking their heads.

A brief scene from my own life in the late Seventies might serve as an illustration:

My wife Barbara and I lived in Madison, Wisconsin, then, and a neighbor used to drop by my garage to hang out while I worked on my Norton Commando or Honda 400F. When I asked if he owned a bike, he said he’d been saving for a brand-new Harley-Davidson for five years. “My dad had Harleys,” he said, “and so did all my uncles. We’re a Harley family, and I’m finally getting a new Electra Glide this summer.”

A few months later I ran into the guy at the grocery store and asked if he’d ever gotten that ’Glide. A high color rose into his face and the veins on the sides of his forehead stood out. I won’t say steam came from his ears, but I got the impression it could happen.

“I got it and now it’s gone,” he said through clenched teeth. “I had transmission trouble, engine trouble, electrical trouble...

LL IMAGES © 2003 H-D, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, SCOTT JACOBS/SEGAL FINE ART, 800/999-1297, WWW.MOTORCYCLEARL.COM

That company will never get another dime out of me.”

I walked back to the house with my groceries, wondering how Harley could afford to lose faithful customers like this, or keep any customers at all without improving its bikes.

Meanwhile, I’d spent a summer roadracing my Honda and had then ridden it to New Orleans and back, all without a single malfunction. At the same time, my new Commando had suffered nearly as many problems as my neighbor’s new Electra Glide. And Norton had just gone out of business.

This unease about Harley’s future was compounded when I moved to California and joined CW as Technical Editor in 1980. Part of my job was to time bikes at the dragstrip when our Executive Editor and test rider, John Ulrich, ran them through the quarter-mile.

Whenever we had a Harley to test, John would look at it ruefully and say, “Well, let’s see if we can make it through a day at the strip with this thing.”

Usually we did, and I don’t remember any catastrophic failures at the dragstrip, or elsewhere. But the Harleys we tested were always slow and shaky compared with other bikes of the time, and they seemed to operate in their own universe of low expectations.

When they didn’t do well in comparison tests, we often got mail accusing us of being “anti-Harley.”

But-strange ly enough-this was not the case at all.

Our Editor, Allan Girdler, was a hardcore flat-track fan, XL owner and Harley historian, and Managing Editor Steve Kimball was a great believer in the virtues of large-displacement, lowrevving engines with torque. Also, the simplicity and perpetual rebuildability of Harleys appealed to something in his Quaker

background, and he would defend these virtues against those who preferred slick but ultimately disposable technology. “No one ever throws a Harley away,” he would say, quite rightly.

And I myself had a natural affinity for Milwaukee’s V-Twins, having grown up in small-town Wisconsin where all motorcycles, essentially, were Harleys. My first motorcycle ride-which turned me toward this sport forever-was on the back of a big Duo-Glide with a buddy seat and a two-tone windshield, and I always loved the appearance and sound of Panhead engines. They looked to me like pairs of cylinders taken right out of one of my favorite radial aircraft engines, blood relatives of the Wright Whirlwind (of which I’d built a cutaway model) or the Continental 220 from a Stearman biplane. Prototypically American designs, with timeless appeal.

But I liked the sound and look of Shovelheads, too, so I volunteered at one of our editorial meetings to do a touring story with one of the last Shovelhead Electra Glides. It was a new 1981 Heritage Edition with a buddy seat and fringed leather saddlebags. This bike was Harley’s first real stab at a retro-look bike, a sort of early Road King, with a solidly mounted engine.

Barb and I took it up the West Coast and back and had a great trip, but by the time we got home the Harley was already cracking parts from vibration fatigue and shedding small pieces of itself

along the highway.

The crash bar around the right saddlebag cracked all the way through, and the springmounted floorboard panels simply disintegrated under my feet. Meanwhile, Barb’s footpeg rubbers kept “walking” off the end of

their pegs and disappearing on the road, and we kept replacing them at Harley dealerships.

But the bike was charismatic, fun to ride at its own leisurely pace and had great visual appeal to a Harley traditionalist such as myself. I had used the tour as a sort of extended test ride to see if I wanted to buy one. By the end of the trip, however, I’d decided the vibration problems were just too destructive to the bike’s long-term wellbeing. (Never mind that I would love to have this bike today, sitting alongside my 2002 FLHT.)

Like everyone else at CW back then, I liked Harleys in concept and wanted the company to survive, but wished they made better machines. I didn’t want them to make an American version of a typical Japanese bike, or change direction radically by developing, say, a high-revving inline-Four; I just wished they would make slightly smoother and more oil-tight versions of their own traditional designs. Just as Norton,

BSA or Triumph should-and might-have done, upgrading conservatively, but without alienating their traditional customers.

Our prayers (for those of us pious enough to pray) were finally answered in the early Eighties.

As is now well known, that’s when a group of Harley executives finally bought the company back from AMF, refinanced, issued stock and set the company off on a path of quality control and redesign. By 1984, the new Evolution engine was replacing the Shovelhead, and engineers took two of the new Evo-powered bikes to Talladega Speedway and hammered them around the banking for four straight days at an 85-mph average.

Suddenly the word was out: Harleys were actually getting better, rather than worse, for the first time in recent memory. Much, much better. While keeping their traditional look and sound, they were evolving into modern,

reliable machines beneath all that chrome and paint.

This message was not lost on a whole generation of new and reentering riders from the famous Boomer generation, or on those who had always been drawn to Harleys but were put off by their frailties.

Timing, as they say, is everything, and Harley both improved its quality and began to dip back into its own vast repertoire of classic styling devices at the exact moment when the 30to 50-somethings of this country (a) finally had enough money to buy a Harley and (b) had cooled somewhat in their love affair with ever more sophisticated technology that seemed to yield ever smaller benefits in aesthetics, riding pleasure and comfort. Not to mention maintenance and resale value.

By 1988, sales had finally climbed back up to their peak level from the 1970s. Among those buyers of Evolution Harleys, interestingly, were four of us former staffers from Cycle World. One of whom was Steve Kimball, my old riding buddy and colleague, who went out and bought himself an 883 Sportster simply because it was such a handsome, no-nonsense basic motorcycle he couldn’t resist.

I called Steve-who now lives in Detroit-the other day to get his thoughts on the resurgence of Harley’s fortunes, and he said, “I think they survived partly by improving their bikes and partly because they never made any really dumb decisions. They never rushed to market with bikes that were not fully developed-as Indian did with its vertical-Twins, for instance-and they didn’t follow any foolish trends that were all wrong for their traditional buyers.

“Harley was fortunate,” he added, “in that they always seemed to have people in charge who knew a bad idea when they saw one.” That dearth of bad ideas, combined with evolutionary improvement, has certainly worked its disarming magic on me over the past two decades. During that time,

ALL IMAGES © 2003 H-D, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, DAVID UHLJSEGAL FINE ART, 800/999-1297, WWW.MOTORCYCLEART.COM

I’ve had an 883, plus Electra Glides in both Evo and Twin-Cam 88 generations, and I currently own a plain-black 2002 Electra Glide Standard.

All these bikes have been among the most reliable, lowest-maintenance motorcycles I’ve owned. Oil changes are easy, tune-ups are cheap and simple, and the valves never need adjusting. Within the limits of their laid-back style (and floorboards), they handle well on the highway and are effortless to ride at low speed. Once rather demanding, Harleys are now, perhaps, the easiest of motorcycles to live with in daily use, whether commuting or running errands.

I own sportbikes that are faster, smoother and better handling, but there’s not much I’d change about the FLH. There’s a certain mood, a relaxed kind of ride, for which a big Harley is exactly right, and nothing else will do.

But that’s just a personal opinion, and many of my hardcore riding buddies don’t see it at all. I can’t argue with them on any logical plane; I can only suggest that beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

Or perhaps, more accurately, in the brain of the beholder-one whose gray matter melds American history, early impressions from childhood, first motorcycle rides, a taste for radial aircraft engines and the concussive benefits of internal combustion that sounds like closelyspaced mortar fire, into a strange amalgam of inexplicable pleasure.

Luckily for Harley, there are quite a few people who share at least some of these visual and mental eccentricities.

Since that turn-around point in the early Eighties, Harley has gone from strength to strength, becoming the darling of investment writers and business analysts. People keep predicting that the sales bubble has to eventually burst, and I suppose some slowdown is inevitable, but there’s little sign of it so far.

In the meantime, the resurgence of Harley-like that of Ducati-has fueled a new climate of fun, social activity and a general renewal of interest in motorcycling as a part of a life well lived. Always a good thing.

And it could so easily have been otherwise.

But it wasn’t, and for that we can probably thank the tenacity of the managers, engineers and line workers, and applaud their refusal to give up the faith or to lose sight of their own heritage.

Harleys, in a strange way, are like the church you grew up in. You hope it will improve with time and become more modem and reasonable, but every time you go home you want it to be exactly the same as it was when you were 10. And, as any theologian will tell you, finding that perfect balance between scientific enlightenment and spiritual conservatism is a daunting task.

But Harley has done a pretty good job of keeping the congregation happy, while finding more than a few new converts. And they’ve kept the candles lit for 100 years. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

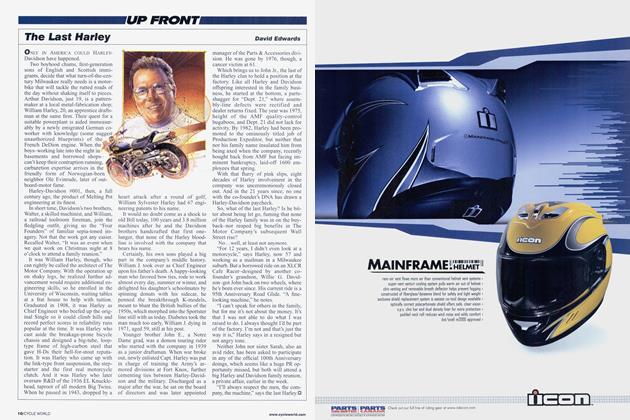

Up FrontThe Last Harley

October 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRevenge of the Soccer Dads

October 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCClutch Players

October 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2003 -

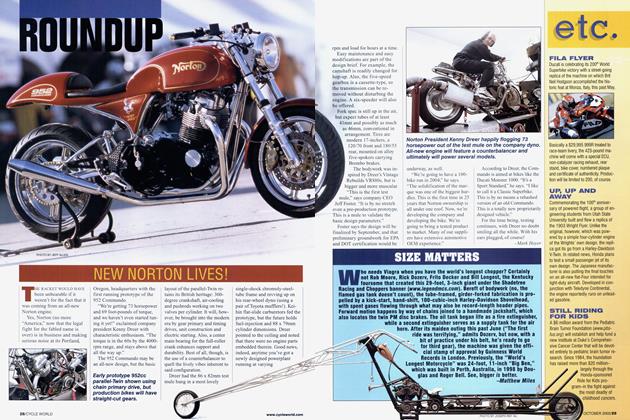

Roundup

RoundupNew Norton Lives!

October 2003 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupSize Matters

October 2003 By Matthew Miles