Triumph Motorcycles in America

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

AT LONG LAST, A BOOK ABOUT TRIUMPH motorcycles that does not come from England.

I thought I was going to have to write one myself, but fortunately a guy named Lindsay Brooke has done it, thereby saving me years of research and dozens of missed Triumph rides on summer afternoons.

The book. Triumph Motorcycles in America, arrived last week by mail, sent to me by the author with a note of thanks for my editing help. Brooke sent me a manuscript of the book about a year ago and asked if I would check it over, a task 1 gladly accepted. This is like being asked to eat cookie dough with a large spoon, with the understanding that you will later tell the cook if it was any good. My kind of job.

In all honesty, however, my editing help was modest at best. Though 1 have owned four Triumphs and followed the news of company fortunes since the early Sixties, I am no trained Triumph historian. Just an attentive fan of the marque. In researching his book, Brooke learned (and now reveals) more about Triumphs than the random owner could hope to discover in a lifetime.

With or without my help, this is the Triumph book I always wanted to read.

Why?

Because nearly all my other British bike books come from England. Which is fine, except that most of them naturally tell the story from an English point of view and tend to immerse themselves in the politics of factory life, while ignoring the fact that North America was generally Triumph’s biggest market. The huge American competition scene is usually mentioned only in passing, as is the considerable impact of Triumphs on American culture.

So Brooke’s 224-page book is quite a relief. Here’s the story of Triumph’s growth in America, with Johnson Motors on the West Coast and TriCor in the East; of racing with Ed Kretz, Bill Baird, Gary Nixon and Gene Romero; of Hollywood’s love affair with Triumphs (Brando, Robert Taylor, Lee Marvin, Keenan Wynn, Steve McQueen and Ann-Margret, no less); of Bonneville speed records, warranty claims, corporate fumbling and wrong turns. It’s all here, nicely written, with lots of good photos.

While the book is naturally a cele-

bration of Triumphs, it also has another side. Careful reading can leave the involved reader with an undeniable sense of sadness and frustration.

In the late Sixties, Triumph was absolutely on top of the world. They had style, racing victories, speed records, social cachet and an on-road/off-road versatility that has not been seen since-at least not in any motorcycle with a claim to aesthetic excellence. Triumph was on a roll.

So what did Triumph’s managers do with this resounding success?

They threw it away in a few short years, that’s what.

Instead of figuring out ways to reduce vibration in the world’s most popular vertical-Twin, they spent millions on a “think tank” where overpaid nonmotorcyclists could ponder the future of design. Instead of investing in simple O-rings and good gaskets to keep the oil inside their engines, they “modernized” with ugly plastic sidecovers and tall oil-in-frame models that sent welding slag straight to the engine innards. Instead of buying new machine tools at the factory, they took big stock dividends and long lunches. Instead of listening to their American dealers’ cries for better quality, they designed Buck Rogers mufflers.

While Japanese workers built the oiltight CB750, British workers went on strike. Or casually dropped the random handful of screws into the crankcase, just to teach Capitalism a lesson.

How a successful company could have made so many bone-headed decisions and fatal errors in such a short

period of time is hard to comprehend, though I suspect a sociologist might attribute it at least partly to the Swinging London Syndrome. The late Sixties and early Seventies were a time when everyone wanted to be a Beatle and smoke dope in Chelsea, but no one wanted to study metallurgy or drill-bit technology. Specificity and real knowledge were out of fashion. Bell bottoms got caught in the drive chain of quality.

Reading Brooke’s book now, a paraphrase of Brando’s famous line from On the Waterfront kept going through my mind: “They could have been a contender.”

By concentrating on the simple things that really mattered to people-smoothness, oil tightness, build quality and long-legged stamina for the road-Triumph could now be England’s version of Harley-Davidson. It turns out there were a lot of people who wanted Harleys, once the company could prove the bikes wouldn’t fall apart, and I suspect the same might have been true of Triumph Twins.

The Triumph name, of course, is alive and well in the hands of John Bloor, with his perfectly modern Fours and Triples. By all accounts, these are excellent bikes (I haven’t ridden one yet), and they certainly look good. No complaints here.

But the old Bonnevilles and Trophies are gone, and I’m not sure they really had to go, despite the wellknown limitations of the large-displacement vertical-Twin. With cleverly integrated counterbalancers and other internal improvements, their lightness and striking good looks (circa 1967) might have put them in the same class as Harley, Ducati and Guzzi V-Twins or BMW’s Boxer, classic designs that never die because they work.

Every time I ride my 1967 TR-6C, it occurs to me that there is no satisfactory modern substitute. I’d still love to buy a brand-new, 380-pound, big-bore roadbike (with Nineties reliability) that can successfully handle cow trails, deserts and continents, win at dirt-tracks, enduros, TTs and Daytona, be ridden solo or two-up, and have chrome an inch deep, beautiful paint and timeless styling.

If someone made such a thing today, I’d probably own just one motorcycle.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

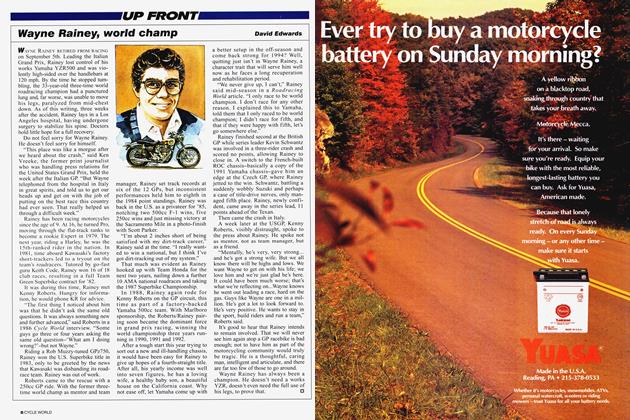

Up FrontWayne Rainey, World Champ

December 1993 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCAnother 100 Years?

December 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki For 1994: Out With the Old, In With the New

December 1993 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupAnother Excellent Oddball From Ktm

December 1993 By Jimmy Lewis -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Gets Racy

December 1993 By Jon F. Thompson