Bonneville

RACE WATCH

The quest for speed between salt and sky

KEVIN CAMERON

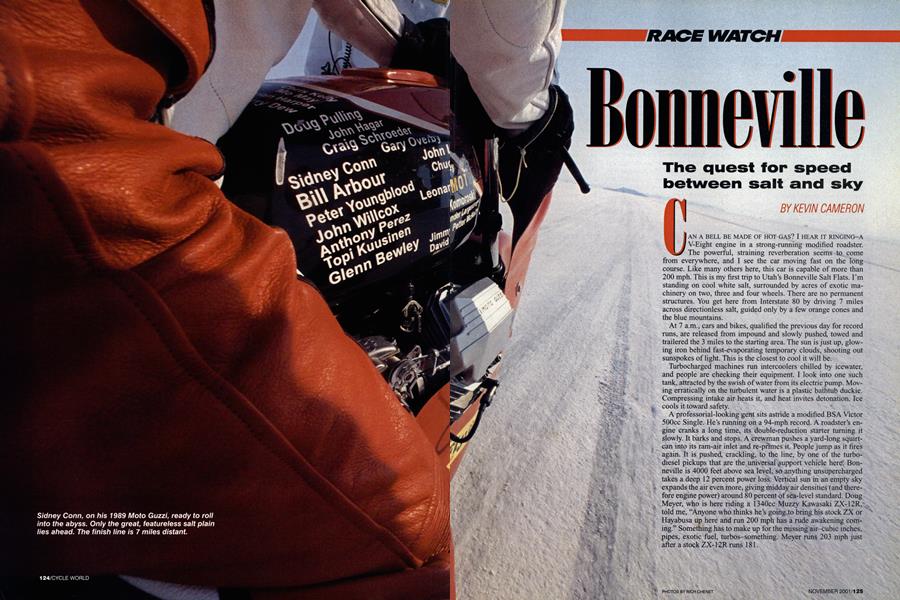

CAN A BELL BE MADE OF HOT GAS? I HEAR IT RINGING-A V-Eight engine in a strong-running modified roadster. The powerful, straining reverberation seems to come from everywhere, and I see the car moving fast on the long course. Like many others here, this car is capable of more than 200 mph. This is my first trip to Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats. I’m standing on cool white salt, surrounded by acres of exotic machinery on two, three and four wheels. There are no permanent structures. You get here from Interstate 80 by driving 7 miles across directionless salt, guided only by a few orange cones and the blue mountains.

At 7 a.m., cars and bikes, qualified the previous day for record runs, are released from impound and slowly pushed, towed and trailered the 3 miles to the starting area. The sun is just up, glowing iron behind fast-evaporating temporary clouds, shooting out sunspokes of light. This is the closest to cool it will be.

Turbocharged machines run intercoolers chilled by icewater, and people are checking their equipment. I look into one such tank, attracted by the swish of water from its electric pump. Mov ing erratically on the turbulent water is a plastic bathtub duckie. Compressing intake air heats it, and heat invites detonation. Ice cools it toward safety.

A professorial-looking gent sits astride a modified BSA Victor 500cc Single. He's running on a 94-mph record. A roadster's en gine cranks a long time, its double-reduction starter turning it slowly. It barks and stops. A crewman pushes a yard-long squirtcan into its ram-air inlet and re-pi~imes it. People jump as it fires again. It is pushed, crackling, to the line, by one of the turbodiesel pickups that are the universal support vehicle here: Bon neville is 4000 feet above sea level, so anything unsupercharged takes a deep 12 percent power loss. Vertical sun in an empty sky expands the air even more, giving midday air densities (and there fore engine power) around 80 percent of sea-level standard. Doug Meyer, who is here riding a 1340cc Muzzy Kawasaki ZX12R, told me, "Anyone who thinks he's going.to brin,g his stock ZX or Hayabusa up here and run 200 mph has a rude awakening com ing." Something has to make up for the missing air-cubic inches, pipes, exotic fuel, turbos-something. Meyer runs 203 mph just afterastockZX-12R runs 181.

The roadster’s engine is idling at 1800 rpm, its stirring sound like military drumming. Looong cam timings are essential to get adequate mixture into twovalve engines-but they pump almost no air below powerband revs. That means “idling” cylinders rhythmically skip cycles to accumulate enough mixture to fire. Continuous-flow fuel-injection threatens to drown the fire, so it’s an art to keep engines clear and running. Pushtrucks get high-geared vehicles up to the bottom of first gear. On the front of each truck is a push-plate. On the back of each car is a horizontal roller. These prevent upset by lateral motion between pusher and pushed. A couple of hundred feet out, the roadster pulls away on its own. It has 2 miles in which to accelerate before hitting the first of three timed miles, after which there are two more miles in which to stop. Unlike brakes, parachutes don’t

get hot and they don’t fade.

Once the engine pulls hard, we know something isn't right. There's an edge to the normal round, bell-like boom. A cou ple of lean cylinders? The car is mostly invisible now behind its white roost of salt. The sound cuts off. A holed piston? The salt is no place for normal high-per formance engines. Thin-crowned pistons from drags or circle-track "overtempera ture" in the heatfiow of five full-throttle miles. Hot pistons provoke detonation to punch through the heat-softened alu minum. Engine oil reaches the hot ex haust valves and pipes, flashing into tell tale white smoke. Tuning for the salt is a delicate balance between what will live and what might set a record.

Harley-Davidson builders are the most desperate. Because their longstroke engines can’t rev like a smallblock Chevy, they make other bets-

monster displacement, suicidally opti mistic supercharging or high-dose nitro or nitrous-oxide. One veteran calls these high-roller engines "exploders." The builders are not discouraged.

I meet a Canadian team whose threeyear plan is to topple the oldest motor cycle records in the book-those set by NSU streamliners in 1956. A Ner-a Car-looking unit is here to develop the powerplant, an alcohol-burning, turbo, intercooled 3 50cc four-cylinder Honda. A streamliner to house it is being tested on airfields back home. If not next year, then the year after!

Wet salt conducts electricity and cor rodes everything. Serious salt vehicles look worn, salt-blasted. People wear 1shirts proclaiming the intimate places into which salt gets. A roadster pilot has his feet brushed to keep the white stuff out of his car. Wiring on well-prepared vehicles is routed separately and labeled, so any fault can be quickly traced. No wire bundles, no tape. One salt racer, frustrated by salt in his connectors and salt in his linkages, burst out, "Where's all this salt coming from?" Fill electrical connectors with insulating grease before assembly. Seal ignition computers into ølastic bags or boxes.

Just being here is work. The risen sun strains the eyes and the brain. People work too hard and dry up-"gotta get that clutch in and get back in line." Dried-out and tired-out, people make mistakes. Drinking water is a discipline. It's sunblock, or bum and hurt. You need shade. Bring a roof and a big hat. Bring generators and fans. Bring water and -4ark glasses.

There's no trash here, and no trash bar rels. All who come take away what they bring. They want the salt to last forever.

The salt agenda is speed, not money and career. Teams are groups of friends. Matching T-shirts are all the uniform you'll see. There are no imagemakers, no art directors. There is mon ey on the salt, but it's all red ink-people are spending it, not to make more, but to enjoy the result. This human purity of purpose is the single most attractive aspect of racing on the salt. All stop to listen respectfully to any very strong, fast run. A Camaro-bodied "altered" passes at an incredible 300 mph, with a big, big sound.

Don Vesco, who has built and driven everything, is here to prepare for next month's international records session. His "Turbinator" is narrow, its right and left wheels only a foot apart. Drive to the front pair is by U-joints and a shaft that runs through a tube at Vesco's left elbow. It's turbine-powered and wheel driven. Al Teague's 400-plus-mph `liner runs up, its exhaust making my eyes sting and nose hurt. That's formalde hyde, a product of partial combustion of alcohol-and likely nitro, too.

John Minonno is riding two turboed, faired Triumphs for Ed Mabry. The sin gle-engine Triple is apart, its turbo spread on a table in front of a technician. Low oil pressure has burned the thrust bearmg, but new parts are here and it will run again in a couple of hours. All the pieces are so tiny, their effect so big.

Turbmator makes clear that there are different goals here. Vesco and Teague just want to go fast. They don't have to look the part-they are the originals. There's braided stainless-steel hose here, but no super-sano Cal custom finish. Other teams want to go fast in beauty and their bikes or cars luxuriate under 20-coats-plus genny gold leaf, with billet everything, color anodized, plated, stainless-steel. That’s their gig. The nomoney runners have cars or bikes older than they are, slowly corroding hot-rod history that’s been through a dozen owners in decades of sporadic reconstruction. A little more power, another tweak, and they might do it again. Retired dragsters are the starting point for many bikes and cars running here because they’re available and close to what you need.

Think Bonneville is nothing but stab ’n’ steer? I asked Doug Meyer about grip. “It’s best early in the morning-the heat of the sun seems to bring more moisture up to the surface later.” Run after run you hear wheelspin-cars and bikes have to feather throttle to get grip. “You have to ride it like it’s a five-mile drag race,” Meyer says. This makes another point: More than one runner notes that too sharp a powerband, or any difficulty in smoothly throttling up after an upshift, and all that carefully cultivated horsepower disappears in white roost. Radical motors equal zero if they don’t hook up.

Traction-finding skill isn’t the only kind. No one has set more motorcycle records here than Scott Guthrie. “See all those 200-mph roadsters on those little tires?” he asked. “Every one of them cuts ruts out there with wheelspin. On a bike, those ruts steer your front and rear wheels-differently.”

Veteran roadracer John Long, trying the salt for the first time, was at first spooked by those wobbles to the tune of several mph. He got the hang of it, but it takes experience to know when to go fast on the salt.

Experience: One motorcycle team came for the first time in 1991 and did the very unlikely-set a record first time out. The next nine times they came, they failed to raise that record. Bonneville is a lot like Daytona-you are never completely, finally ready. The best you can do is raise your learning curve, remembering, anticipating, correcting, so that given infinite time, your curve flattens out and runs almost parallel with (but mostly just below) success. Anyone lacking humility can get help here. Age is no reason to stop running on the salt. What a person may lose in reaction time is more than made up in experience gained. You can do this racing forever.

When streamliners run, you see them sink slowly into the salt as they pass over the horizon. That’s right-you can see the curvature of the earth here.

Tradition is roadsters, Hillbom injection, S&S or Holley carbs, and reading plugs like holy writ. The new way is systems, sensors and software. A Japanese team with a turbo Toyota Supra played the new game, their instrumented 3 liters reportedly making 1400 bhp. They came to the line cold, fired and went 239 mph. Ken Hardman, a young Chrysler engineer who with friends built his own car around a Yamaha FZR1000 engine, engineering its injection and turbo system themselves, coaxed it to 209 mph. Sensors and software don’t solve every problem, but the laptop people are here.

The classic problems are alive and well. Take unequal fuel distributionsome rich cylinders and some lean ones. In aircraft, lean backfires used to blow whole intake systems off of engines. Here, it still does. One team’s shattered supercharger lay in pieces near their car. Richen up? Okay, but that trades away speed for survival.

Pushing air is the big problem. “Air crushers” are classes whose blunt shapes are fixed by rules. This includes roadsters and unstreamlined motorcycles. Pile on power and hope for traction. Top streamliners like Vesco’s have four-wheel drive to translate all their weight into grip. Lots of cars and bikes carry lead or iron. For slenderness and mechanical convenience, some cars have staggered front wheels, one ahead of and slightly offset from the other. The fastest cars are so narrow now that they are almost motorcycles-low frontal area is a key to running over 400 mph on a single engine. The great streamliners of> the past, like John Cobb’s 394-mph monster, were of normal widths and so needed aircraft engines to go fast. Today’s tiny ’liners can go faster because a de-tuned dragster engine makes 1800 bhp with a whiff of reliability. Behind tiny frontal area, that’s enough.

Dynamic pressure is what results if the airflow’s kinetic energy is completely converted to pressure on the front of your machine. At 200 mph, that’s 100 pounds per square foot of frontal area. At 350 mph, it’s 315 pounds per square foot. A streamlined shape cuts this loss by diverting the airflow smoothly around you instead of stopping it cold. Its success in doing this is measured by the coefficient of drag-the smaller, the better. For pro duction cars, this lies in the range of .32 to .45. For bikes, it's higher because they are short, unable to close their airflow be hind. Aero drag is dynamic pressure times drag coefficient times frontal area. Make it slick. Make it small.

Classic streamlined bodies-fish and birds-are largest near the front, using most of their length to taper back to the smallest possible base area. This puts the airflow back together with the least loss. Despite this, do-it-yourself engi neering still builds many Bonneville runners as wedges, sharp and slender in front, wider toward the rear. As Ken Hardman remarked, "A bunch of these cars would go faster backward."

Why do people come here? Some call it "the great white dyno' but numbers on a time slip aren't everything. I think Bon neville's elemental otherness is perverse ly attractive-the lifeless lunar mountains, the shimmerrng heat, the empty salt as scary as complete freedom. It's a perfect setting for purity of purpose.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAfter the Fall

November 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFirst Bikes

November 2001 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupSneak Peek! 2003 Ducati Multistrada

November 2001 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

November 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupOld Pro, New Suspension

November 2001 By Allan Girdler