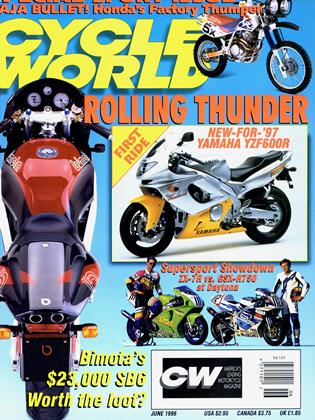

MIGUEL AGAIN!

RACE WATCH

After a week’s rain delay and 200 miles of racing, Daytona was won by a wheel-length

KEVIN CAMERON

I KNOW MY FRONT WHEEL WAS FIRST across the line, but I’ll bet his rear wheel crossed it before mine.” Thus Miguel Duhamel described winning the rain-delayed 55th running of the Daytona 200 over threetime winner Scott Russell. “Mr. Daytona” was just .010 second behind-less than two revolutions of the crankshaft.

Russell, who vows he’ll be back for a crack at his fourth victory, said of Duhamel, “He won this race. He deserves it.”

In practice, all eyes were on Troy Corser, qualifying a towering second and a half above the rest of the field on his Promotor Ducati 955, the bike that does everything well. Suzuki, with its all-new GSX-R750 to demonstrate to the world, brought three teams: the U.S. Yoshimura Suzuki squad, the justformed World Superbike team and a special, Lucky Strike-sponsored group supporting Russell. Asked about the Russell team, manager Garry Taylor replied, “I asked for, and I got, the Suzuka 8-Hour crew.” Heavy hitters.

Duhamel, the reigning U.S. Superbike Champion, attracted little attention during Speed Week, qualifying a modest > eighth. But, as Honda team boss Gary Mathers later noted, when Duhamel won the 200 in 1991, he had qualified 11th. There is more to winning this race than just being fast.

Despite this, Corser’s dominance of qualifying was stunning. This hardfaced and experienced young man showed his virtuosity by wheelying out onto the West Banking and clear around the west wall in the final practice. But qualifying is an exciting abstraction; a major ingredient is short-lived qualifying rubber-tires designed to sacrifice themselves in three to five laps of hard running, to produce unreal, temporary grip. Another is qualifying engines-built with more violent cams, less durable valves and other parts, to make extra power for a short time. Crucial was Corser himself, and his determination to make that brilliant lap in high, gusting wind.

Two abilities score especially high at Daytona. One is to know what the winning pace will be, and to sustain it without loss of concentration. The other is the ability to switch plans instantly. Experienced men take adversity in stride, tame ill handling, baby fading tires, recalculate and press on regardless. All teams planned two pit stops for fuel and tires, and all were elaborately equipped with jacks, air wrenches and special wheels with quick-release everything.

The early leaders were, unsurprisingly, Corser, Colin Edwards (Belgarda World Superbike Team Yamaha), Anthony Gobert (WSB Muzzy Kawasaki), and Russell, with Yosh Suzuki men Aaron Yates and Pascal Picotte heading a second group behind.

Gobert pitted early-standard Muzzy practice-again on lap 16 for consultation, then in for good on lap 22 with an engine that wouldn’t rev out. On the ninth lap, Edwards was in for tires; one had begun to vibrate. Riders know this indicates blistering or chunking. Volatile components in the rubber, when overheated, foam the rubber up. Pieces are flung off, causing the imbalance. In general, the faster the tire, the shorter its life, so the drive to build a winning tire forces all makers close to the edge.

On lap 29, a Turn 1 crash threatened to become a pile-up, bringing out the pace car. Russell led from Duhamel, who was himself forced to pit three laps early with tire vibration. The small Smokin’ Joe’s Honda crew wasn’t quite ready, but saved the situation. Behind them, the Yosh Suzuki riders, Picotte and Yates, cruised competently.

Corser dominated half the race, but his temp gauge was climbing and his downshifts were becoming sluggish. During the pace-car laps, he came in for good with his engine making dreadful noises. Promotor Ducati teammate and rookie sensation of the 1995 U.S. Superbike season, Mike Hale, qualified second for this race, only to crash on oil after five laps. The Ducati threat crumbled.

Racing resumed, but Russell slowed abruptly into Turn 2, then headed in with a puncture. Edwards, who had overcome the handicap of his unscheduled tire stop, now took the lead, outbraking Duhamel into the Chicane. Interest swung away from Russell as this new lead group swapped places. Duhamel’s corner exits had weakened. Was his rear rubber fading under his long, smooth, tire-spinning exits from Turn 6, the transition from infield to banking? Handling specialist Dale Rathwell had suggested that tire spin may be the only way the Honda RC45 can finish a turn. With its Vee-engine putting more weight on the rear, less on the front, hard acceleration can make the front tire push, and the bike run wide. >

Meanwhile, Russell was calculating. With his forced, lap-34 stop for fresh rubber, he had naturally taken on fuel-and now he realized he had enough to race to the finish, 23 laps without another stop.

“I don’t care if they tell me to gas,” Russell recalls thinking, “I’m not stopping.”

He pushed on with this in mind-far from the lead. But the upcoming fuel stops would cancel the leaders’ apparent advantage. On lap 42, Duhamel pitted, leaving the Edwards/Picotte/ Yates trio up front, but when all the stops were finally complete on lap 46, Russell and Duhamel again held joint custody of the race.

It would come down to a last-lap dash from chicane to finish line. Would Russell succeed with a classic, drafting-from-second-place pass? Would either man try for a decisive advantage before that? Would Russell’s rear tire, or his fuel, go the distance? As the laps unwound, we could see the two measure each other, on brakes, on acceleration, on top speed. It looked equal. By lap 55, Russell was positioned in Duhamel’s draft. On the final lap, the two plunged into the Chicane. Duhamel knew Russell needed his draft for the acceleration to pass, and now he was determined to break that draft. As he exited the Chicane, he ran his bike right up to the wall, then snatched it left again, breaking loose the back tire at a frightening speed, in a frightening place.

“When I pulled it in, the back end broke away,” Duhamel recounted.

It worked. Russell was forced to follow or lose the draft. Accelerate he did, but tracking Duhamel’s violent move took time he didn’t have. Tenthousandths of a second.

The finish order was Duhamel, Russell, Edwards, Picotte and Kawasaki’s Doug Chandler-four brands in the top five. It was a triumph for Duhamel and his team, and a great achievement for Russell and Suzuki’s brand-new GSX-R.

New-tech for this year might have been variable-intake-length systems for carburetors, but when AMA staff saw notice of Honda’s device in the British press, it was banned the next day. Variable intake length can cancel dips in the power curve that occur with a fixed length. The system used >

by Honda and Kawasaki is very simple, reportedly, just sliding an extension bellmouth away from each carb on a linear track when the shorter length is desired. This two-state system neatly eliminated a torque dip at 12,200 rpm on the Honda, but the ban forced the team back to a less satisfactory compromise. VIL systems tested by Ducati and Yamaha may be continuously variable. All teams will use them in World Superbike this season.

The War of the Radiators rages, and Suzuki leads. The new GSX-R’s rad fills the entire fairing cross-section from under the headstock right down to the bellypan-and Yosh reportedly added more core thickness during practice week! By contrast, the Ducati rad measures only 14 inches wide by 7 inches high-about half the area. It’s obvious from track performance that power isn’t proportional to radiator area, so what gives? Suzuki’s GP tech manager Stu Shenton said, “It’s really more of a watertank than a radiatorcooling air can hardly get through most of it.” He noted that the Suzuki rad is actually bigger than that on a 700-horsepower Formula 1 car-but on an F-l car, there is room for intake and exit ducting. “It’s one of the compromises,” he summed up.

How do the Ducatis manage? Well, Corser’s didn’t, but one effect that helps a Twin is its reduced ratio of displacement-to-cylinder surface area: More of a Twin’s combustion gas is located far from a cylinder wall, where it can’t reject heat to coolant. Another is that, on a narrow V-Twin, there’s a clearer airflow path out the back of the radiator. Was the small Ducati rad part of Corser’s problem? Stay tuned; if the 955s come with big-

ger rads next year, we’ll know.

About the new Kawasaki ZX-7RR motor, Rob Muzzy said, paradoxically, “Our engine has the highest redline, but the strongest midrange.” Thus far, he said, there’s been no horsepower increase from the shortened stroke (was 46mm, now 44.7) and revised valve mechanism (was finger-type, now inverted bucket). He continued, “If you look carefully at the new castings, you’ll see lumps and bumps where there’s nothing inside. That’s to make room for the gear (cam) drive that’s coming in the (race) kit.”

Honda manager Gary Mathers explained Kawasaki’s interest in gear drive: Chain stretch changes timing and >

causes horsepower loss in long races.

Talk of the garages was chassis stiffness, and how to avoid having too much. The problem is that, when leaned over, a bike’s suspension is at 60 degrees to the action of the bumps-so it becomes almost useless. Letting the steering-head twist a bit, and the swingarm flex laterally, can deal with in-corner bumps better, but only up to a point. Beyond that, the flexing frame is just a spring without a damper, an oscillator potentially out of control. Just as, a decade ago,

everyone was suddenly measuring mass properties (moments of inertia around the three axes), today, everyone is analyzing chassis stiffness in terms of individual components. One visible proof was the reinforcing plates welded to the top of the Yamaha headstock and chassis beams. Stock chassis have nothing here, but the racebikes had plates 12 inches long. To prevent this from making the bike too stiff when leaned over in turns, a more-flexible, 42mm fork is used.

Another technique is to actually use a falling-rate suspension link, to make suspension softer when “hunkered down” in corners. Yamaha, in desperation, used this on its super-stiff GP bike in 1993. The need for a separate, lateral suspension is again a hot concept-an idea of great interest to the late John Britten.

Dunlop basked in hot rays of publicity over its “dual-compound” tire, a >

concept that has been discussed for at least 25 years that I know of. Now we learn that everyone’s doing it, but only Dunlop is talking. The trick is to find two compounds-one soft enough to work on the cooler, right-hand side of the tire, the other durable enough to survive high-speed running on the banking-that can be cured with chemically compatible systems. Dunlop’s tire has a visible line, located about 20mm to the left of center, where the two compounds join, but it disappears once the tire is scrubbed.

This year’s wide distribution of the new Dunlop had its effect; riders were clearly faster through Turn 2 (a right-hander) than in previous years.

Racing is expensive, and it will get worse as Superbike morphs into four-stroke GP racing. The parts in the new GSX-R race kit total more than $100,000-and those are just the parts that are for sale. The only Hondas in the 200 were factory machines, reportedly leased from Japan at $300,000 each, and I saw no RC45 streetbikes in the parking lot. Jim France, son of Speedway and NASCAR founder Bill France, expressed the fear that motorcycle racing may grow only until it bursts. Today is a golden age, with all major factories on the start grids, and close competition. No single team can quit without appearing to do so from weakness. But all can agree to quit to-

gether, once all are thoroughly broke. Are the AMA and FIM strong enough to hold racing to a “sustainable level” of expense? Or will the teams be allowed to raise the stakes until they have to fold?

While that interesting question is being decided, at least we can enjoy the show. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue