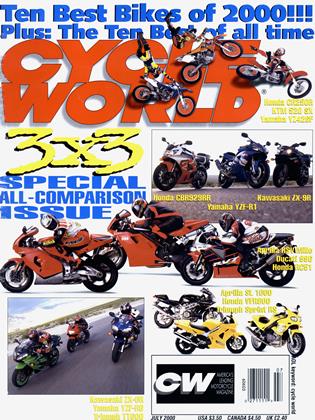

TEN BEST MILLENNIUM

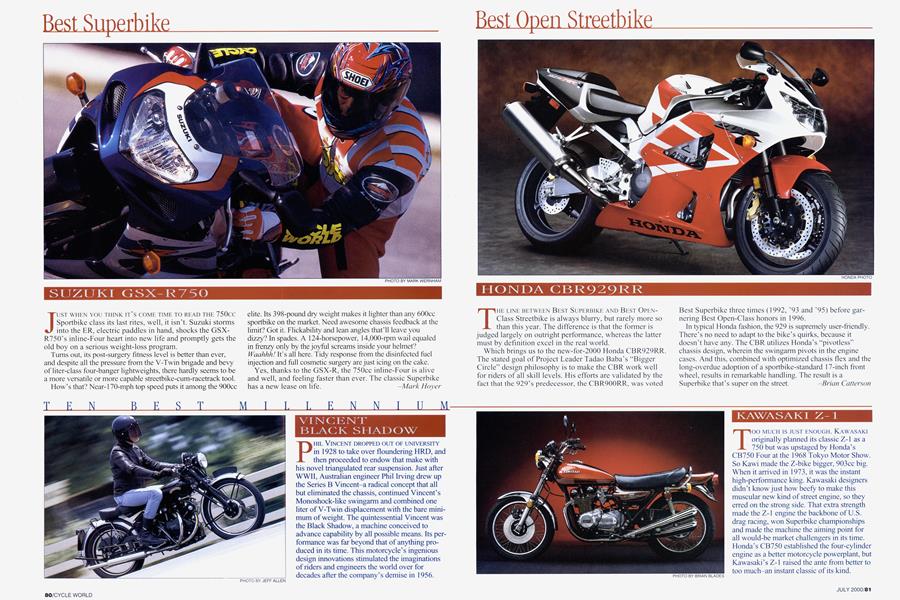

VINCENT BLACK SHADOW

PHIL VINCENT DROPPED OUT OF UNIVERSITY in 1928 to take over floundering HRD, and then proceeded to endow that make with his novel triangulated rear suspension. Just after WWII, Australian engineer Phil Irving drew up the Series B Vincent—a radical concept that all but eliminated the chassis, continued Vincent’s Monoshock-like swingarm and combined one liter of V-Twin displacement with the bare minimum of weight. The quintessential Vincent was the Black Shadow, a machine conceived to advance capability by all possible means. Its performance was far beyond that of anything produced in its time. This motorcycle’s ingenious design innovations stimulated the imaginations of riders and engineers the world over for decades after the company’s demise in 1956.

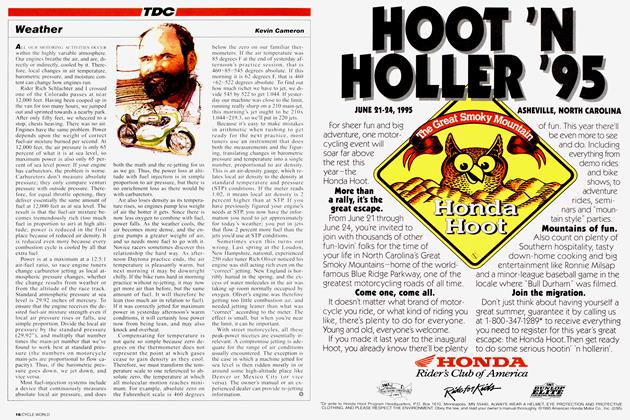

KAWASAKI Z-1

TOO MUCH IS JUST ENOUGH. KAWASAKI originally planned its classic Z-l as a 750 but was upstaged by Honda's CB750 Four at the 1968 Tokyo Motor Show. So Kawi made the Z-bike bigger, 903cc big. When it arrived in 1973, it was the instant high-performance king. Kawasaki designers didn’t know just how beefy to make this muscular new kind of street engine, so they erred on the strong side. That extra strength made the Z-l engine the backbone of U.S. drag racing, won Superbike championships and made the machine the aiming point for all would-be market challengers in its time. Honda’s CB750 established the four-cylinder engine as a better motorcycle powerplant, but Kawasaki’s Z-l raised the ante from better to too much-an instant classic of its kind.

BSA GOLD STAR

WHY AREN'T WE PICKING A HOT LATEmodel 600 here? Because BSA's legendary Gold Star was the univer sal motorcycle, a machine that excelled on the road, on flat-tracks, in roadracing, scrambles and observed trials. It was all things to all riders-a quality that today’s offerings have all but ignored. Robust power from a 500cc single-cylinder four-stroke engine was adaptable without being expensive. Moderate weight, factory options backed by a strong aftermarket and rugged cycle parts contributed to its versatile performance. Yesterday’s universal motorcycle has now been refracted by the prism of the marketplace into many separate, specialized identities. The Gold Star personifies the original white light from which this refraction began.

BMW R69S

BMW's POSTWAR MACHINES WERE STAID but reliable. They would run on any gas, accept nonexistent maintenance, plod on forever. When auto production resumed after 1950, European bike sales fell, and the motorcycle had to seek new identities. Since the war, it had been basic transportation. What came next? A few people wanted highquality motorcycles for touring, BMW’s traditional role. Sporting qualities were selling a comparative flood of English motorcycles.

Could sport and touring be combined? In 1960, BMW made the connection in its R69S, a 600cc sport-touring version of its venerable flat-Twin. Uprated with more power, it reached a maximum speed of more than 100 mph while losing none of the gentlemanly virtues for which BMW s were known.

HARLEY-DAVIDSON ELECTRA GLIDE

THE LARGE AMERICAN MOTORCYCLE WAS AT first not a touring machine at all, but a heavy, Jeep-like runabout whose rigid frame and big, slow-turning engine had evolved to handle the rough roads of prewar America. After the war, its evolution progressed in step with improvements to the nation’s highways. First came the soft, long-stroke Hydra-Glide telescopic front end in 1949. Then the DuoGlide of 1958 added swingarm rear suspension with telescopic struts, providing all-around automobile-like comfort. The final civilizing element was electric starting, arriving with the 1965 Electra Glide. On this big, comfortable motorcycle, equipped at the rider’s option with luggage and weather protection, you no longer had to be a hardy pioneer to cross the nation.

CROCKER V-TWIN

AL CROCKER WAS A Los ANGELES INDIAN dealer in the years just before WWII, who saw no reason why he couldn’t produce as good a motorcycle as any factory. His first were single-cylinder speedway bikes, but in 1935 he planned an ohv 61-cubic-inch Twin. Crocker knew what his customers wanted and he knew the kinds of modifications they liked to make. Why not produce that bike? In those days, West Coast customizers were building “bobbers’-machines pared to functional essentials, with shortened fenders, tiny seats and hot engines. Crocker built just that. With more power and less weight than contemporary Indians and Harleys, the Crocker was guaranteed to outperform both. Al Crocker’s concept of the factory-produced custom was decades ahead of its time.

HONDA CB750

TIRADITIONAL BRITISH MAKERS OWNED THE large-displacement field in the 1960s. They studied and rejected the possibility of building smoother, more powerful four-cylinder bikes. Too complex and expensive. Soichiro Honda did not agree. His engineers knew that modem production methods could deliver exotic features like overhead cams, multi-speed gearboxes, electric-starting and disc brakes at marketable prices. The four-cylinder, sohc, fivespeed CB750 Honda was the result, a pioneering design that used liberal doses of automotive technology to simplify the engine’s complexity-and put countless thousands of riders on Honda Lours. The CB750 established the four-cylinder engine as the right powerplant for a new kind of motorcycle, combining high performance with refinement and convenience.

YAMAHA DT1

IN ITS EARLY DAYS IN THE U.S., OFF-ROAD motorcycling was practiced by only a small number of knowledgeable, experienced people on Triumph, Matchless or even NSU motorcycles modified for the purpose. The coming of Japanese “street scramblers” did nothing to change this-one magazine review of the time called them “overweight streetbikes with high pipes, bash plates and warty tires.” The Japanese were willing to take advice if it led to success. Yamaha’s DT-1 was the first bike designed by a U.S.-side team, specifically for American conditions. It combined 250cc of two-stroke power with manageable weight to deliver credible on/offroad versatility. Available from any Yamaha dealer, its reliability and low price triggered an off-road explosion here.

PENTON 175 JACKP INER

JOHN PENTON WAS AN ENDURO RIDER IN SEARCH of a bike, but in the early 1960s found no motorcycle made for what he wanted to do: off-road enduros. Existing bikes were burdened with brazed lug-and-tube chassis and heavy four-stroke engines. Penton wanted something light and handy that wouldn’t tire its rider out. He pitched European makers but found little interest. Then KTM, an Austrian moped maker, signed on. Early models featured peaky Sachs 125 two-strokes in light welded tubular chassis. Production bikes arrived in the U.S. in 1968, but the definitive Penton was the Jackpiner of 1971, powered by a KTM-designed 175cc twostroke. This machine was light at 251 pounds, powerful without being as demanding as the 125, and changed enduro riding forever.

BULTACO PURSANG

THE FIRST EUROPEAN MOTOCROSSERS WERE heavy four-strokes. When the two-stroke Husqvama, CZ and Greeves machines arrived, their modest performance still matched boggy European conditions. It was humorously suggested that the toughest riders could carry their machines faster than their machines could carry them. Spanish bikes evolved in drier terrain similar to U.S. conditions, particularly those in Southern California. Bultaco’s idea was to put 30 horsepower into a 200-pound machine and see what happened. The yellowtanked prototypes had Rickman Metisse chassis, but blood-red production bikes wore the Pursang name, with fine Spanish water-pipe replica frames. To get revolutionary Pursang performance, riders here were happy to weld up a few frame cracks.

Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest, 2000

July 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Perfect Baja Bike

July 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

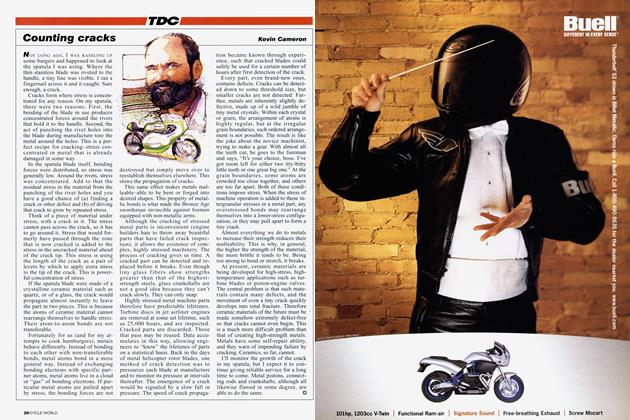

TDCCounting Cracks

July 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupFriedel Münch Strikes Again

July 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Buys Moto Guzzi

July 2000 By Bruno De Prato