Working all night

TDC

Kevin Cameron

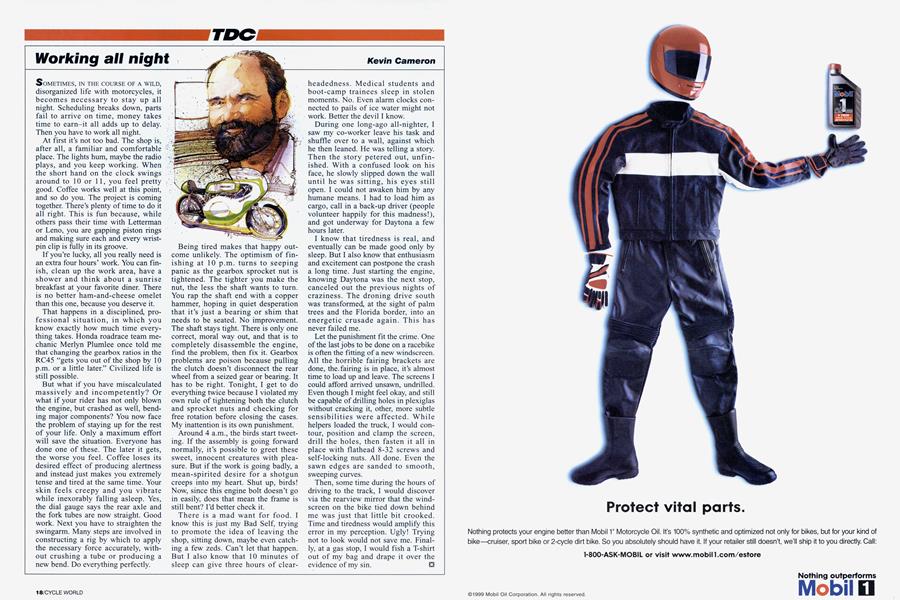

SOMETIMES, IN THE COURSE OF A WILD, disorganized life with motorcycles, it becomes necessary to stay up all night. Scheduling breaks down, parts fail to arrive on time, money takes time to earn-it all adds up to delay. Then you have to work all night.

At first it’s not too bad. The shop is, after all, a familiar and comfortable place. The lights hum, maybe the radio plays, and you keep working. When the short hand on the clock swings around to 10 or 11, you feel pretty good. Coffee works well at this point, and so do you. The project is coming together. There’s plenty of time to do it all right. This is fun because, while others pass their time with Letterman or Leno, you are gapping piston rings and making sure each and every wristpin clip is fully in its groove.

If you’re lucky, all you really need is an extra four hours’ work. You can finish, clean up the work area, have a shower and think about a sunrise breakfast at your favorite diner. There is no better ham-and-cheese omelet than this one, because you deserve it.

That happens in a disciplined, professional situation, in which you know exactly how much time everything takes. Honda roadrace team mechanic Merlyn Plumlee once told me that changing the gearbox ratios in the RC45 “gets you out of the shop by 10 p.m. or a little later.” Civilized life is still possible.

But what if you have miscalculated massively and incompetently? Or what if your rider has not only blown the engine, but crashed as well, bending major components? You now face the problem of staying up for the rest of your life. Only a maximum effort will save the situation. Everyone has done one of these. The later it gets, the worse you feel. Coffee loses its desired effect of producing alertness and instead just makes you extremely tense and tired at the same time. Your skin feels creepy and you vibrate while inexorably falling asleep. Yes, the dial gauge says the rear axle and the fork tubes are now straight. Good work. Next you have to straighten the swingarm. Many steps are involved in constructing a rig by which to apply the necessary force accurately, without crushing a tube or producing a new bend. Do everything perfectly.

Being tired makes that happy outcome unlikely. The optimism of finishing at 10 p.m. turns to seeping panic as the gearbox sprocket nut is tightened. The tighter you make the nut, the less the shaft wants to turn. You rap the shaft end with a copper hammer, hoping in quiet desperation that it’s just a bearing or shim that needs to be seated. No improvement. The shaft stays tight. There is only one correct, moral way out, and that is to completely disassemble the engine, find the problem, then fix it. Gearbox problems are poison because pulling the clutch doesn’t disconnect the rear wheel from a seized gear or bearing. It has to be right. Tonight, I get to do everything twice because I violated my own rule of tightening both the clutch and sprocket nuts and checking for free rotation before closing the cases. My inattention is its own punishment.

Around 4 a.m., the birds start tweeting. If the assembly is going forward normally, it’s possible to greet these sweet, innocent creatures with pleasure. But if the work is going badly, a mean-spirited desire for a shotgun creeps into my heart. Shut up, birds! Now, since this engine bolt doesn’t go in easily, does that mean the frame is still bent? I’d better check it.

There is a mad want for food. I know this is just my Bad Self, trying to promote the idea of leaving the shop, sitting down, maybe even catching a few zeds. Can’t let that happen. But I also know that 10 minutes of sleep can give three hours of clear-

headedness. Medical students and boot-camp trainees sleep in stolen moments. No. Even alarm clocks connected to pails of ice water might not work. Better the devil I know.

During one long-ago all-nighter, I saw my co-worker leave his task and shuffle over to a wall, against which he then leaned. He was telling a story. Then the story petered out, unfinished. With a confused look on his face, he slowly slipped down the wall until he was sitting, his eyes still open. I could not awaken him by any humane means. I had to load him as cargo, call in a back-up driver (people volunteer happily for this madness!), and got underway for Daytona a few hours later.

I know that tiredness is real, and eventually can be made good only by sleep. But I also know that enthusiasm and excitement can postpone the crash a long time. Just starting the engine, knowing Daytona was the next stop, canceled out the previous nights of craziness. The droning drive south was transformed, at the sight of palm trees and the Florida border, into an energetic crusade again. This has never failed me.

Let the punishment fit the crime. One of the last jobs to be done on a racebike is often the fitting of a new windscreen. All the horrible fairing brackets are done, the.fairing is in place, it’s almost time to load up and leave. The screens I could afford arrived unsawn, undrilled. Even though I might feel okay, and still be capable of drilling holes in plexiglas without cracking it, other, more subtle sensibilities were affected. While helpers loaded the truck, I would contour, position and clamp the screen, drill the holes, then fasten it all in place with flathead 8-32 screws and self-locking nuts. All done. Even the sawn edges are sanded to smooth, sweeping curves.

Then, some time during the hours of driving to the track, I would discover via the rearview mirror that the windscreen on the bike tied down behind me was just that little bit crooked. Time and tiredness would amplify this error in my perception. Ugly! Trying not to look would not save me. Finally, at a gas stop, I would fish a T-shirt out of my bag and drape it over the evidence of my sin. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue