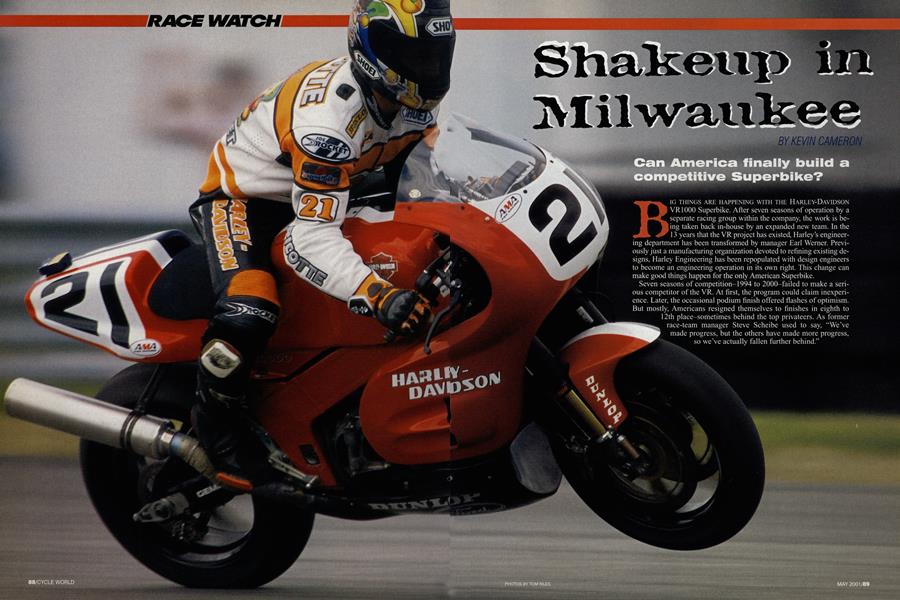

RACE WATCH

Shakeup in Milwaukee

Can America finally build a competitive Superbike?

KEVIN CAMERON

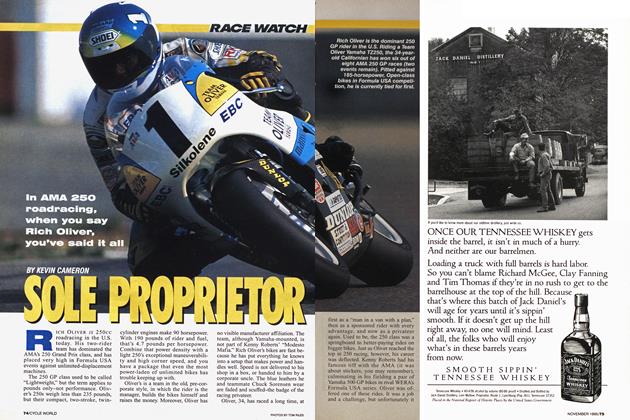

BIG THINGS ARE HAPPENING WITH THE HARLEY-DAVIDSON VR1000 Superbike. After seven seasons of operation by a separate racing group within the company, the work is being taken back in-house by an expanded new team. In the 13 years that the VR project has existed, Harley's engineering department has been transformed by manager Earl Werner. Previously just a manufacturing organization devoted to refining existing designs, Harley Engineering has been repopulated with design engineers to become an engineering operation in its own right. This change can make good things happen for the only American Superbike. Seven seasons of competition-1994 to 2000-failed to make a serious competitor of the VR. At first, the program could claim inexperience. Later, the occasional podium finish offered flashes of optimism. But mostly, Americans resigned themselves to finishes in eighth to 12th place-sometimes behind the top privateers. As former race-team manager Steve Scheibe used to say, “We’ve made progress, but the others have made more progress, so we’ve actually fallen further behind.”

I've stuck with Harley on this be cause I hoped one day to see it proved that your name doesn't have to be Horikoshi or Bordi to design a top racebike. Mechanical engineers of all nations learn the same subjects, after all. Even so, in the last two seasons I gave up hope, retaining only a grudg ing admiration for The Motor Compa ny's ability to hang in there and take the derision of the enthusiast press. Harley management came to feel the same way, and last summer decided to bypass channels and get their own facts. They loaded up the corporate jet with engineers, speed guns, stopwatch es and laptop computers, and flew them to the Laguna Seca Superbike races to find out what was missing.

The VR program came into being in the late 1 980s. Although Erik Buell and perhaps others designed chassis for it, it was Englishman Mike Etough's de sign that was built. The engine from the head gasket down was the province of Harley staff engineers, but the crucial cylinder head was farmed out to Jack Roush's organization. A Roush employ ee, Scheibe was later hired by Harley to head the VR program.

The resulting design had merit. Etough's twin-aluminum-beam chassis carried the compact 60-degree V-Twin engine well forward. Marelli fuel-injec tion fitted into the Vee while the fivespeed gearbox nestled under the rear cylinder. Four valves in each cylinder were driven by a combination of gears and chains. Called to comment on the new engine, legendary former race chief Dick O'Brien said in his usual salty manner that he believed the intakes were "too goddamned big" and the flywheel mass "too goddamned small."

The resulting engine had no powerband, no "hit." It also had lots of prob lems-both large and small. At an early test session I attended, most of the time was occupied with changing electronic parts and batteries. These problems would remain with the team for two more years. In practice for its first event, the 1994 Daytona 200, one of the bikes exploded its engine and spread oil past start-finish. The pri mary balance shaft had "dephased," which means that it had smashed into the crankshaft after its drive sheared. I never saw more cell phones in simulta neous use in one garage. Clutch bas kets fractured. Electric fuel pumps that went 100,000 miles in cars lasted 20 minutes in the yR. Later, connecting rods broke, the fuel system vapor locked and piston crowns caved in. A newly designed six-speed gearbox ini tially rounded off its engagement dogs.

All of this happened right out in public-not under wraps as other teams do it. It was depressingly like the early days of NASA, when in a blaze of media attention the Vanguard rocket rose 4 feet off its launch pad, settled back and exploded.

To further compound the mystery, two years ago at Daytona hard-working factory VR rider Pascal Picotte cracked off a front-row qualifying lap of 1:49.235 When I asked Scheibe and other team members what had happened, no one had any idea.

The lap time was never repeated, but there it stoodincredible proof that some favorable combination of VR parts could go really fast.

What did the planeload of Harley fact-finders find? So far, there has been no "Deep Throat" to leak revealing documents to Cycle World (Harley's security service is more effec tive than anything in Washington), but the result was a rumble that could be felt far from Milwaukee. Insiders couldn't say much except that ______ everything was up for review. They found, of course, what all people in racing knew all along-that there was no research and development effort to swiftly bring the VR, or a possible suc cessor, to maturity as there is with Aprilia's RSV 1000 or Honda's RC5 1.

When the race team loaded up to go to the races, the last man to leave the shop turned off the lights. As Scheibe him self said last March, "We're not doing any R&D. We're just looking for the

best combination among the hardware options open to us." This is like young bachelors looking in the dirty-clothes hamper for the least stinky underwear to put on. Harley is a cash-rich company,

but there was no evidence of rows of dyno cells running around the clock, no separate test team backing up newfound power with the handling to get that pow er to the ground.

Change was manda tory. A great deal of money has been spent on the YR in ` years past, but the program ignored the vast wealth of racing talent here in the U.S., preferring to rely on paid advice and oth erwise to keep to itself To outsiders, it looked a lot like planned failure. No one could ex plain it.

My worst fear in the fall of 2000 was that change would change nothing. The forces in play, long stalemated, had thus far failed to validate the VR program. The “change,” if it came at all, might simply re-adjust these forces into a fresh, more comfortable stalemate. After a flurry of press releases vibrant with evangelistic business buzzwords, Harley Racing could return to its old ways with all the same faces. I hoped not. Therefore I called up people I knew at Harley and challenged them: “Say it ain’t so, Joe.”

They immediately offered me a choice: Either fly to Carolina Motorsports Park for the first session of the new test team, or come to Milwaukee to meet the new racing manager, John Baker. I picked the Milwaukee option because at this point, the important story is software, not hardware. I wanted to hear about change.

Communications Manager Paul James (himself an active amateur roadracer) took me to a small conference room in

the company’s hallowed Juneau Ave. brick building. The lights clicked on automatically. Moments later, Baker entered. He is a substantial young man with an intelligent, watchful face. He spoke the language of management, but with substance, and it

was clear that he understood the history and predicament of the Harley racing effort. He was entirely straight about the problems. Baker impressed me as being a man of action with authority behind him. Previously, he was platform manager for the Buell Blast, and was involved in VR production in 1994.

As Baker spoke, I realized what has happened at Harley since the VR program began. I knew that top man Werner had originally come to Harley Engineering from being Chevrolet’s head of Corvette. Werner had quit and moved to Harley rather than be promoted to manage a major GM auto division. Moving from Corvette to bread-and-butter sedans didn’t interest him. The special problems of motorcycles did. In a conversation shortly

thereafter, Werner revealed that he had big, long-range plans for motorcycles.

“People tell me,” he said, “that to pass EPA we have to get rid of air cooling and rolling bearings. That’s not true. If we apply engineering to air cooling and rolling bearings, we can get the results we need without destroying the character of our product. The job of engineering is to give us what we want-not just what engineering wants.”

Later, at the Nashua, New Hampshire, introduction of the new counterbalanced Twin Cam 88 engine, Werner described to me tests they had devised to solve some of the problems of oil control, heat distortion and noise. I was introduced to the designer of the Big Twin’s thoroughly modern new shifting mechanism. I could see Harley had changed under Werner.

In the past, the company had devoted itself to propping up outdated solutions and preserving traditions. When I interviewed for a job at Juneau Ave. in 1966,

I sat across from a man whose background was 20 years at Allis-Chalmers tractors. He told me Harley was suspicious of college graduates who always tried to change things. They preferred to train their own people, straight out of high school drafting courses.

The tides of history have carried that world away. Werner’s engineers are modern professionals who, like Werner himself, have chosen motorcycles over automobiles as a career.

Maybe at the time when Scheibe worked so hard to separate the racing department from engineering, he was right to do so. But not only has Harley Engineering changed, so has the attitude of engineering toward racing. In

the past, racing versus engi neering was truly a tissue-re jection situation. Racing was about instant soiutions, and officiai en gineering was about the annual styling change. Mixing the two would damage both. Today, instant engineering is the lifeblood of the vehicle biz, with the constant need to anticipate federal reg ulators, stay ahead of the market and develop products and refinements that will keep the brand competitive. Mod ern automotive technology has been changed by racing, so contact with rac ing is now seen as extremely valuable. The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) holds its Motorsports Engineer ing Conferences to deliberately bring the two sides together. Engineering managers know that the excitement of motorsports motivates young engineers-a useful antidote to un relieved corporate life. Companies like Aprilia use racing as a tonic for the whole company. Rotating engineers through racing on a regular basis keeps them sharp and interested, much as Swissair keeps its pilots sharp by regularly assigning them to mountain rescue flying. Racing is more than just advertising. It is also an internal business tool.

I asked Baker, “How will you make the VR competitive?”

“Two things,” he replied evenly. “We’ll develop good ideas in our group of bright, motivated people. And we’ll iterate fast.” Continuing, he explained that there would be both a formal R&D department with dynos running and machine tools humming, and a track test team-separate from race operations. No more turning the lights out when the team transporter rolls. As I am writing this, the new test team is running its first familiarization session with the VR at Carolina Motorsports Park.

In addition, the relationship with Ford and Cosworth Engineering is moving to a higher level of engagement-and spending. Some ideas > have already emerged from this. Ford believes it can contribute to VR aero dynamics, and you may have read about the lighter crankshaft evaluated at the off-season Laguna Seca test. Twelve new people have been hired onto the race team-most of them from within Harley. More experienced rac ing people are being sought.

Iterate fast? That means make it, test it `til it breaks, redesign it and test it again until it works the way you want it to. It means trying new ideas now, not just wondering if they'd work. It means tracking down powerband trends to dig out all their potential, using all existing test and analytical tools. No~ more of the old wartime outlook If we had some ham, we could have ham and eggs-if we had some eggs.” Ideas and testing are the ham and eggs.

Twice during his remarks, Baker made the point that Harley believes racing has always been a part of its identity-and must remain part of it. “We’re in this activity to stay,” he said.

Baker returned to his work and I went to lunch with Erik Buell. How many people know that Buell was himself a privateer roadracer, a veteran of the Yamaha TZ750 wars of the late 1970s? Throughout the VR era, Buell has been the heckler in the back row, like Richard Feynman at Los Alamos, constantly raising his hand, objecting, making unsolicited suggestions. I wanted to hear his views on the changes in the VR program, and see his face. Erik’s not much use at concealing his true feelings.

"I have plenty to do (at Buell Motor Co.) without thrusting myself into af fairs over there (at the new race opera tion), but I think it looks good," he said. In my past conversations with Buell, he always seemed deeply frustrated and almost speechless when the VR came up. I saw none of that now. Scheibe is gone, but there is respect for his work in establishing the VR program and in keeping it alive through many knife's-edge annual re views. Equally important in the VR's survival has been the doggedness of Pascal Picotte. He has always pushed

through the combinations in practice to find something he could race. Then he has ridden it hard to some kind of real result.

I hope to return to Harley soon to see the new Racing Development Center and its work. Success, if it comes, will take time. Improvement can be immediate.