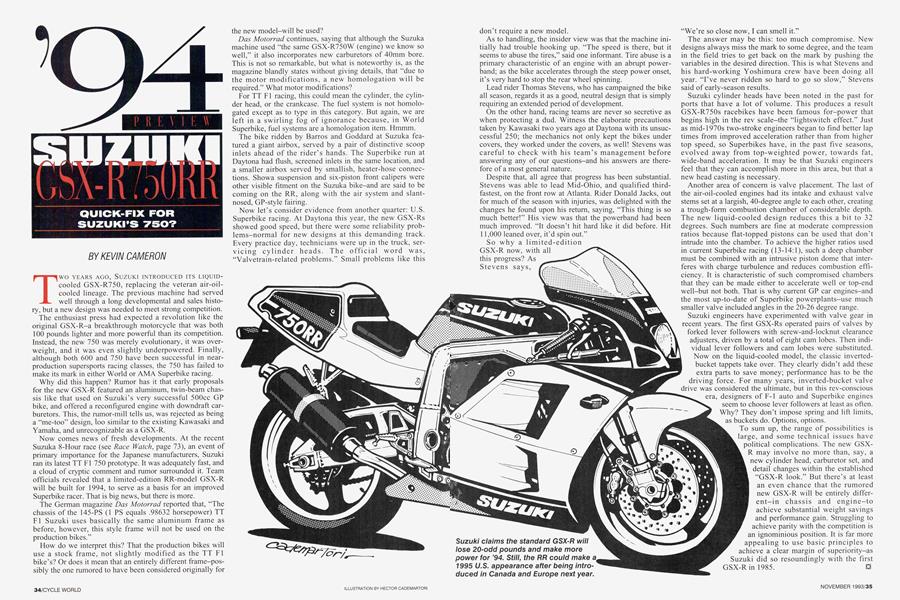

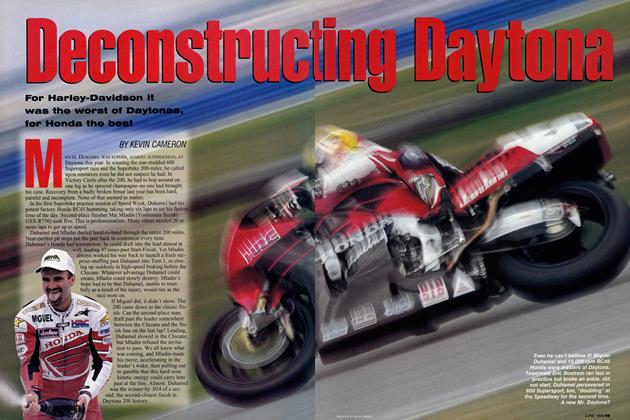

SUZUKI GSX-R750RR

'94 PREVIEW

QUICK-FIX FOR SUZUKI'S 750?

KEVIN CAMERON

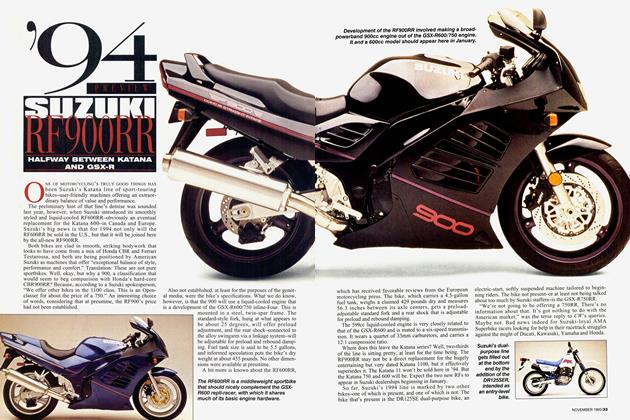

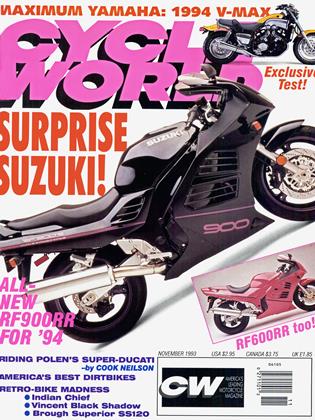

TWO YEARS AGO, SUZUKI INTRODUCED ITS LIQUID-cooled GSX-R750, replacing the veteran air-oil-cooled lineage. The previous machine had served well through a long developmental and sales history, but a new design was needed to meet strong competition.

The enthusiast press had expected a revolution like the original GSX-R-a breakthrough motorcycle that was both 100 pounds lighter and more powerful than its competition. Instead, the new 750 was merely evolutionary, it was overweight, and it was even slightly underpowered. Finally, although both 600 and 750 have been successful in nearproduction supersports racing classes, the 750 has failed to make its mark in either World or AMA Superbike racing.

Why did this happen? Rumor has it that early proposals for the new GSX-R featured an aluminum, twin-beam chassis like that used on Suzuki’s very successful 500cc GP bike, and offered a reconfigured engine with downdraft carburetors. This, the rumor-mill tells us, was rejected as being a “me-too” design, too similar to the existing Kawasaki and Yamaha, and unrecognizable as a GSX-R.

Now comes news of fresh developments. At the recent Suzuka 8-Hour race (see Race Watch, page 73), an event of primary importance for the Japanese manufacturers, Suzuki ran its latest TT FI 750 prototype. It was adequately fast, and a cloud of cryptic comment and rumor surrounded it. Team officials revealed that a limited-edition RR-model GSX-R will be built for 1994, to serve as a basis for an improved Superbike racer. That is big news, but there is more.

The German magazine Das Motorrad reported that, “The chassis of the 145-PS (1 PS equals .98632 horsepower) TT FI Suzuki uses basically the same aluminum frame as before, however, this style frame will not be used on the production bikes.”

How do we interpret this? That the production bikes will use a stock frame, not slightly modified as the TT FI bike’s? Or does it mean that an entirely different frame-possibly the one rumored to have been considered originally for

the new model-will be used?

Das Motorrad continues, saying that although the Suzuka machine used “the same GSX-R750W (engine) we know so well,” it also incorporates new carburetors of 40mm bore. This is not so remarkable, but what is noteworthy is, as the magazine blandly states without giving details, that “due to the motor modifications, a new homologation will be required.” What motor modifications?

For TT FI racing, this could mean the cylinder, the cylinder head, or the crankcase. The fuel system is not homologated except as to type in this category. But again, we are left in a swirling fog of ignorance because, in World Superbike, fuel systems are a homologation item. Hmmm.

The bike ridden by Barros and Goddard at Suzuka featured a giant airbox, served by a pair of distinctive scoop inlets ahead of the rider’s hands. The Superbike run at Daytona had flush, screened inlets in the same location, and a smaller airbox served by smallish, heater-hose connections. Showa suspension and six-piston front calipers were other visible fitment on the Suzuka bike-and are said to be coming on the RR, along with the air system and slantnosed, GP-style fairing.

Now let’s consider evidence from another quarter: U.S. Superbike racing. At Daytona this year, the new GSX-Rs showed good speed, but there were some reliability problems-normal for new designs at this demanding track. Every practice day, technicians were up in the truck, servicing cylinder heads. The official word was, “Valvetrain-related problems.” Small problems like this don’t require a new model.

As to handling, the insider view was that the machine initially had trouble hooking up. “The speed is there, but it seems to abuse the tires,” said one informant. Tire abuse is a primary characteristic of an engine with an abrupt powerband; as the bike accelerates through the steep power onset, it’s very hard to stop the rear wheel spinning.

Lead rider Thomas Stevens, who has campaigned the bike all season, regards it as a good, neutral design that is simply requiring an extended period of development.

On the other hand, racing teams are never so secretive as when protecting a dud. Witness the elaborate precautions taken by Kawasaki two years ago at Daytona with its unsuccessful 250; the mechanics not only kept the bikes under covers, they worked under the covers, as well! Stevens was careful to check with his team’s management before answering any of our questions-and his answers are therefore of a most general nature.

Despite that, all agree that progress has been substantial. Stevens was able to lead Mid-Ohio, and qualified thirdfastest, on the front row at Atlanta. Rider Donald Jacks, out for much of the season with injuries, was delighted with the changes he found upon his return, saying, “This thing is so much better!” His view was that the powerband had been much improved. “It doesn’t hit hard like it did before. Hit 11,000 leaned over, it’d spin out.”

So why a limited-edition GSX-R now, with all this progress? As Stevens says, “We’re so close now, I can smell it.”

The answer may be this: too much compromise. New designs always miss the mark to some degree, and the team in the field tries to get back on the mark by pushing the variables in the desired direction. This is what Stevens and his hard-working Yoshimura crew have been doing all year. “I’ve never ridden so hard to go so slow,” Stevens said of early-season results.

Suzuki cylinder heads have been noted in the past for ports that have a lot of volume. This produces a result GSX-R750s racebikes have been famous for-power that begins high in the rev scale-the “lightswitch effect.” Just as mid-1970s two-stroke engineers began to find better lap times from improved acceleration rather than from higher top speed, so Superbikes have, in the past five seasons, evolved away from top-weighted power, towards fat, wide-band acceleration. It may be that Suzuki engineers feel that they can accomplish more in this area, but that a new head casting is necessary.

Another area of concern is valve placement. The last of the air-oil-cooled engines had its intake and exhaust valve stems set at a largish, 40-degree angle to each other, creating a trough-form combustion chamber of considerable depth. The new liquid-cooled design reduces this a bit to 32 degrees. Such numbers are fine at moderate compression ratios because flat-topped pistons can be used that don’t intrude into the chamber. To achieve the higher ratios used in current Superbike racing (13-14:1), such a deep chamber must be combined with an intrusive piston dome that interferes with charge turbulence and reduces combustion efficiency. It is characteristic of such compromised chambers that they can be made either to accelerate well or top-end well-but not both. That is why current GP car engines-and the most up-to-date of Superbike powerplants-use much smaller valve included angles in the 20-26 degree range.

Suzuki engineers have experimented with valve gear in recent years. The first GSX-Rs operated pairs of valves by forked lever followers with screw-and-locknut clearance adjusters, driven by a total of eight cam lobes. Then individual lever followers and cam lobes were substituted. Now on the liquid-cooled model, the classic invertedbucket tappets take over. They clearly didn’t add these extra parts to save money; performance has to be the driving force. For many years, inverted-bucket valve drive was considered the ultimate, but in this rev-conscious era, designers of F-l auto and Superbike engines seem to choose lever followers at least as often. Why? They don’t impose spring and lift limits, as buckets do. Options, options.

To sum up, the range of possibilities is large, and some technical issues have political complications. The new GSXR may involve no more than, say, a new cylinder head, carburetor set, and detail changes within the established “GSX-R look.” But there’s at least an even chance that the rumored new GSX-R will be entirely different-in chassis and engine-to achieve substantial weight savings and performance gain. Struggling to achieve parity with the competition is an ignominious position. It is far more appealing to use basic principles to achieve a clear margin of superiority-as Suzuki did so resoundingly with the first GSX-R in 1985. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue