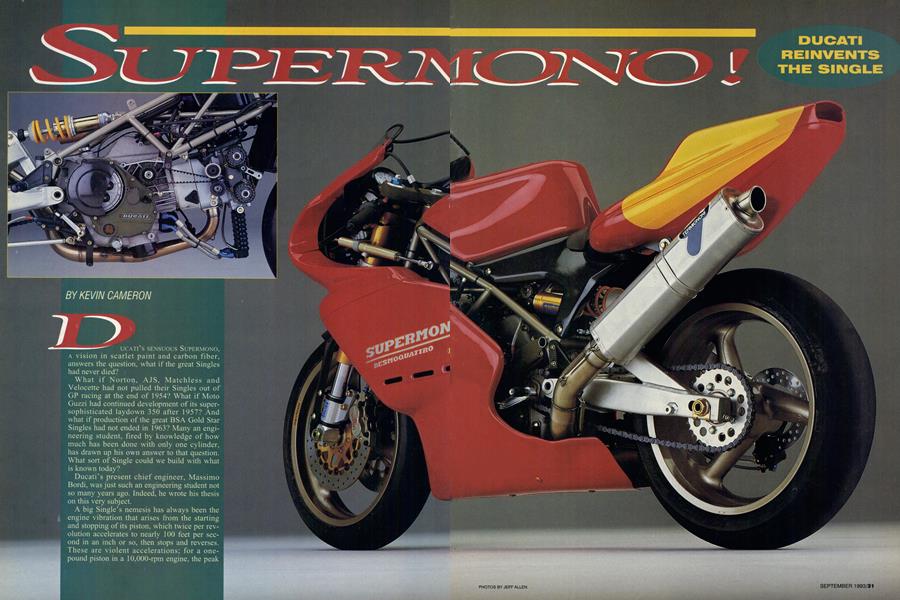

SUPERMONO!

KEVIN CAMERON

DUCATI'S SENSUOUS SUPERMONO, A vision in scarlet paint and carbon fiber, answers the question, what if the great Singles had never died?

What if Norton, AJS, Matchless and Velocette had not pulled their Singles out of GP racing at the end of 1954? What if Moto Guzzi had continued development of its supersophisticated laydown 350 after 1957? And what if production of the great BSA Gold Star Singles had not ended in 1963? Many an engineering student, fired by knowledge of how much has been done with only one cylinder, has drawn up his own answer to that question. What sort of Single could we build with what is known today?

Ducati’s present chief engineer, Massimo Bordi, was just such an engineering student not so many years ago. Indeed, he wrote his thesis on this very subject.

A big Single’s nemesis has always been the engine vibration that arises from the starting and stopping of its piston, which twice per revolution accelerates to nearly 100 feet per second in an inch or so, then stops and reverses. These are violent accelerations; for a one-

pound piston in a 10,000-rpm engine, the peak forces considerably exceed one ton.

DUCATI REINVENTS THE SINGLE

These forces react on the engine, kicking it back and forth. The piston and the engine vibrate back and forth around their common center of mass-the piston through its stroke, the engine as a whole through a smaller but significant distance called the “vibratory excursion” (its length determined by the ratio of piston mass to engine mass). This vibration of the engine is transmitted to the chassis and, ultimately, to the rider. It prompts bolts to loosen, fuel to froth in carburetor float bowls, and causes both metal and the rider to fatigue. Vibration is a great nuisance.

Because piston motion takes place in a straight line, it cannot be completely canceled by placing counterweights on the revolving crankshaft. Only an opposite, straight-line force can do that. The best we can do with crank counterweights is to put on enough to completely balance the rotating parts (the big end of the rod, its bearing and crankpin) and to balance about 50 percent of the purely reciprocating parts (the piston, rings, wristpin and small end of the rod). As we add counterweight to balance the reciprocating parts, vibration along the cylinder axis does decrease-but at right angles to it a new imbalance appears, created by the whirling counterweight. What have we gained? To reduce one imbalance, we have created another.

This is one reason Singles fell from favor and multi-cylinder designs came to the fore. Engineers found it was much easier to use the imbalance of one piston to cancel that of another-for example, in the case of BMW’s classic Boxer (opposed-piston) Twin. With more cylinders, the problem becomes easier, for two reasons. First, by setting the crankpins at the proper angles, one imbalance cancels another, and second, the smaller pistons of engines with many cylinders weigh less, so whatever imbalance they cause cannot kick the engine around as much as can one massive piston.

There are other schemes using rotating counterweights that can improve single-cylinder balance, but they are complicated, based on the idea that a pair of counter-rotating shafts turning at crank speed, each carrying a balance weight, can generate a straight-line shaking that will largely cancel the shaking of a piston. This works because the side-to-side components of the two counterweights’ imbalance cancel out, leaving only an up-and-down component. For a Single, whose major attraction is simplicity, this seems excessive.

A single balance shaft can be paired with the counterweight already on the crank to achieve a similar effect, but since the balance shaft has to be off to one side, the resulting forces can’t act along the cylinder centerline, leaving a so-called “rocking couple,” which is a rhythmic twisting of the whole engine.

Ingegnere Bordi surely considered and rejected these ideas as too complex, too crude or simply ineffective. He wanted to tum his notional Single to rpm levels that would have shaken a Manx Norton engine right out of its mounts, so the vibration had to go.

A lot has changed since the days of the great Singles. They had long strokes approximately equal to their bores, and all that piston motion limited their rpm. Right at the end of the classic period, development engines were tested with shorter strokes and bigger bores, but the work went nowhere. The Singles of the 1950s had two valves, set at a wide angle of 60 degrees or more, requiring a tall, intrusive piston dome for high compression. Combustion was slowed by the folding of the chamber over the piston. For his Supermono, Bordi would instead adopt the modern style of large bore, short stroke, with plenty of valve area from four valves set into a nearly flat cylinder head that achieves high compression with a featureless, almost-flat piston top.

All well and good, but how to deal with the vibration?

Bordi’s answer was to make a Single mimic a Twin. It is well-known that a 90-degree V-Twin has excellent balance.

The crank counterweights are set at 100 percent of rotating weight and 100 percent of reciprocating weight. In a Single, this would simply redirect the shaking from the cylinder axis to the axis at right angles to it. But on a Twin, there is already shaking at right angles-caused by the presence of the other cylinder. These two shaking forces cancel, leaving the engine smooth. Neat. Bordi would build his Single with two connecting rods, one connected to the power piston, the other to a dummy piston, operating at right angles to the power cylinder, with the sole purpose of providing balance. This would actually work better than balance shafts, for it would balance both primary (arising from the simple rise and fall of the piston) and secondary (a second-order, double-time motion caused by the effective “shortening” of the rod’s height as it swings from side to side) imbalances.

Once there was enough in Ducati’s lean research budget to fond the work, a 487cc, 95.6 x 68mm prototype was built, based upon an 851 V-Twin’s crankcase with only the horizontal cylinder and head producing power. This employed the largest practical bore, plus an available production stroke. With desmo valvetrain and electronic fuel injection and ignition, it was effectively half of Ducati’s World Superbike title-winning Twin. Although it gave 53 horsepower on its first dyno run, Bordi was disappointed. The factory Nortons of 1937-54 gave close to 50 horsepower; Bordi wanted more progress than that from 40 years of technology. The 57 horsepower that resulted from refinement was still disappointing. The natural habitat of the Supermono was the new Sound of Singles racing class, and it would take more than 57 bhp to compete with the likes of race-tuned 800cc Suzuki DRs or super-modified Yamaha SRXs.

The problem? Friction and crankcase-pressure effects were eating into Bordi’s hoped-for power. Formula One carengine designers now carefully avoid having adjacent pistons entering the case together because of the pressure and wasteful high-speed internal airflows it generates. Bordi’s dummy piston, even with rattling, loose clearance, was still shearing a large cylinder-wall oil film, loaded by the large inertia forces of the piston and con-rod. Bordi’s prototype was a Single, carrying a Twin’s friction burden.

Yet the idea was right, for the engine was smooth. Now Bordi would get rid of most of the friction by eliminating the dummy piston. In its place he put a lever, joined to the small-end of the balance con-rod, and at right angles to it. The far end of the lever pivoted on a pin fixed in the crankcase. The weight of the small-end of the rod, plus the oscillating mass of the lever, added up to the previous reciprocating mass. Balance was preserved, but pumping and oilfilm losses were cut. The engine also became more compact; gone were the dummy cylinder and the extra height of its piston. The only external evidence of the balance scheme was a slight bulge in the top of the crankcase.

This is elegance of a high order. First, this doppia bielletta (double con-rod) balance system is as unique as Ducati’s desmodromic valve gear. Second, it is economical to build.

desmodromic valve gear. Second, it is economical to build.

As Ing. Bordi has said, “If it costs 100,000 lire to build two counterbalance shafts, then a single balance shaft costs 50,000 lire, the “blind piston” balancer 40,000 lire. But the doppia bielletta costs only 25,000 lire.” Further, the resulting crankcase can be machined on the same tooling as Ducati’s production-line Twins-an important economy for a small company.

With the new system, the little 487cc engine, spinning at 10,500 rpm, gave 62.5 horsepower at the engine sprocket. Subsequently, using a special larger cylinder and modified cylinder-stud pattern to permit a stout 100mm bore, plus a crank with 2mm of extra stroke, the developing Supermono has grown to 549cc and a claimed 75 horsepower at 10,000 rpm. Bordi predicts more; the Twin’s tuning is compromised for smooth power delivery, while the Single needs every scrap of power it can be given. Once the Supermono is specifically tuned for its own needs, more power will appear.

There is one aspect of a Single’s motion that can never be balanced: The large torque pulses twist the engine around its own crank. There is a torsional shock absorber to smooth this, but there is charm in being able to feel a Single’s quantized delivery of power-part of the character that makes a Single attractive in our era of electric-motor-like Fours.

And there is utility for the Supermono beyond Sound of Singles racing, beyond even the contemplated MonoSport production machines that are in the pipeline. The Single is a convenient mule for Bordi’s development of the 851/888/916 Twin. Recall that the current V-Twin Ducati carries its crank in four rolling-element main bearings-two major bearings plus outriggers to oppose crank bending. The Supermono’s simple pair of plain bearings is an attractive alternative to this-probably lighter, certainly stronger, and quieter-an important concern as the new European Economic Community prepares to impose new noise standards.

How does this remarkable engine integrate into a motorcycle? First comes the value of balance. By not emitting frame-shattering vibration, the Supermono engine can be bolted solidly into its 851-like multi-tube steel spaceframe, supplementing rigidity and saving considerable weight. Remember that a conventional tooth-loosening Single must either be rubber-mounted, or everything within range of its hideous motion must be made extra-thick and robust just to survive. Whatever extra weight a balancing scheme may cost is more than repaid in lighter structure weight, extended parts lifetimes and reduced rider fatigue. Next, the low height of the Supermono engine has inspired the low and slinky Pierre Terblanche-designed styling of the motorcycle as a whole: There is nothing lower than a horizontal Single. In the days of Ing. Giulio Carcano’s 250/350 Guzzis, it was the superior direction-changing agility of his horizontal engine, far more than mere power, that gave the design its long success. It will be interesting to see his concept return to action, competing as before against tall, vertical engines.

Ducati’s new Supermono is a beautiful creation, full of individual character, elegant in concept, a pleasure to behold. And it’s red.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

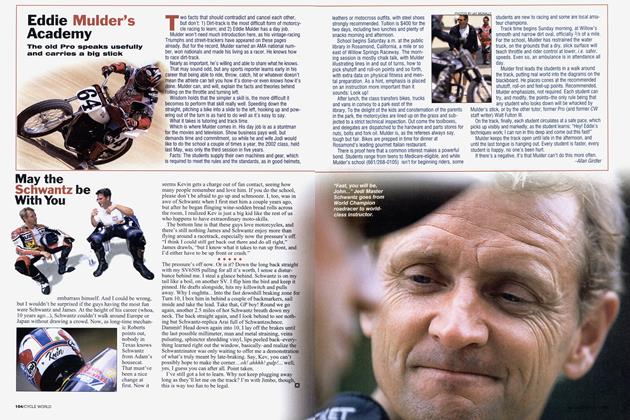

Up FrontTomb of the Unknown Harleys

September 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsDo Loud Pipes Save Lives?

September 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCVicious Cycles

September 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupBmw Sings A Song of Singles

September 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupPick A Pair of Yamaha 600s

September 1993