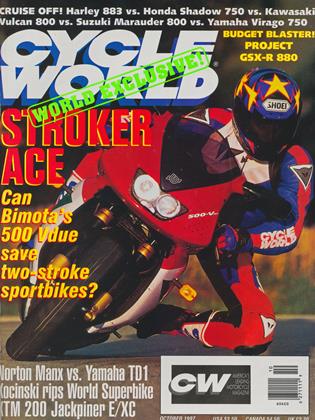

Really nice racebikese

TDC

Kevin Cameron

THE SUZUKA 8-HOUR IS THE MOST IMportant single roadracing event of the year, displaying the sharpest part of the Japanese cutting edge. But in the U.S., the top equipment appears either at Daytona, where the factories break the bank within AMA Superbike rules, or at the Laguna Seca round of World Superbike.

Daytona has come and gone. Laguna brings its special slice of international gossip, and a look at middling-to-high technology. At Daytona, Suzuki’s geardriven cam kit was a rumor. At Laguna, both the Kawasakis and Suzukis were running gears. Kawasaki geardrive makes that gravel-crusher backlash noise at idle, and GSX-R750 cam gears whistle piercingly at speed. Gear drive preserves accurate timing all the way to the end of events, when chains have worn and come slightly out of time.

To give them Ducati-like punch, WSB Hondas like John Kocinski’s have received reshaped powerbands. Some 6-8 horsepower have been added in the middle, and perhaps 4 have been taken from the top. This makes last year’s variable-length intake system unnecessary. A parallel reason for the change is to make the bikes throttle-steer better. Hondas from the RC30 onward have looked short of wheelbase, and tall. To check this, I compared crank height and wheelbase between a Muzzy Kawasaki (noted for its forgiving slow motion when sliding) and a retired Camel Honda. Result? The Kawasaki is a full inch longer, at 55.7 inches, and the crankshaft centerline of its widerlooking inline-Four is actually an inch lower than the Honda V-Four’s crank. Both cause greater braking/acceleration weight shift on the Honda, and that in turn may require stiffer, busier suspension to prevent extreme attitude change during braking and acceleration. One thing leads to another.

To enhance braking power, Honda has its mysterious underseat, solenoid-operated brake device. It applies the rear brake an instant before the front, in a pulse adjustable from Vioo to Vio of a second. Brake torque, applied through the swingarm, lowers the back of the bike. Combined with front brake dive, this lowers the bike’s eg enough to permit usefully more powerful braking. The rider, meanwhile, holds the back end down with a Doohan-type thumb brake.

Kocinski was audibly using the fat

midrange to steer the back of his Honda at the bottom of Laguna’s Corkscrew. When I spoke of this to Rob Muzzy, he replied, “That’s the only way they can steer them.” A short chassis with a tall eg puts precious little weight on the front tire when accelerating!

The Suzukis went up Laguna’s hill well, but their riders were shooting corners like they were on 250s, keeping apex speed high to avoid any unnecessary display of weak midrange acceleration.

Doug Chandler’s Laguna setup was different from most in that it was “loose.” His bike would squat slightly at the upshift off Turn 4, while almost all others were solidly topped. You could also see his rear suspension work at the bottom of the Corkscrew. This is part of his package of developing a lot of rear grip, allowing him hard, early acceleration without having to wait for the machine to come nearly upright. He is a master at this. Unfortunately, he had to run his spare Kawasaki in the second race, and its clutch failed. Nevertheless, he showed again that he can run at the top of WSB.

Ducati was once again the blow-up king, thanks to overworked crankcases and thin cylinder liners. Now there are new crankcases, cylinders and heads, with bigger valves and ports. An unlooked-for result of this is some loss of the famous Ducati acceleration. The added metal is mostly far back in the chassis, which hurts steering, and the bigger intake system probably hurts bottom and middle torque. Dukes are still fast, but WSB isn’t the one-sided contest

it once was. Carl Fogarty has wished for his 1995 bike, but is still, through hard riding of the kind he showed at Laguna, at the top of the points battle.

Colin Edwards didn’t ride (injured wrist), leaving Scott Russell as the only WSB Yamaha rider. Compare his bike, decelerating for Turn 4, with the AMA Superbike Yamaha of Tom Kipp. The WSB bike popped and banged loudly like Chandler’s Muzzy Kawasaki, indicative of longer cam timing and especially overlap. Kipp’s machine, like most of the Suzukis, was almost silent, save for a few little pops. The fuel-injected Hondas and Ducatis, naturally, were completely silent on deceleration because their fuel systems cut off.

In early practice, Russell’s YZF750 was a handful after the bottom of the Corkscrew, where riders must flick over from full-right to full-left turning, under power. The Yamaha shook violently and even popped the front wheel up, but Russell just muscled it and put up with the wiggling. Chandler, on the other hand, paused at the top of the roll to move his butt over, and this quieted the bike down. The WSB ZX7Rs of AkiraYanagawa and Simon Crafar, with their big braced sheetmetal swingarms, rolled right over without complaint.

The Ducatis seemed to have the best all-around mix of qualities, but the mix was weaker this year. The Hondas had horsepower, but as always, quirky handling, partly civilized by clever engineering. Kawasakis had outstanding grip and line-holding ability, but Chandler would like more acceleration. Yamaha’s ascent toward the top runs along lines parallel to Kawasaki’s, but is offset by the handicap of five valves (low combustion speed) and a shorter time in the class. Suzuki is struggling, as its WSB team showed less speed than their American counterparts.

Steve Whitelock, formerly Yvon Duhamel’s mechanic on Kawasaki two-stroke Triples, and now the WSB tech inspector, announced rather expansively that, taken as a whole, “These bikes have become, in the past year, really nice racebikes.”

The AMA’s competition director, Merrill Vanderslice, cautioned that along with this change has come steady loss of WSB entries. Really nice racebikes can be really expensive. □