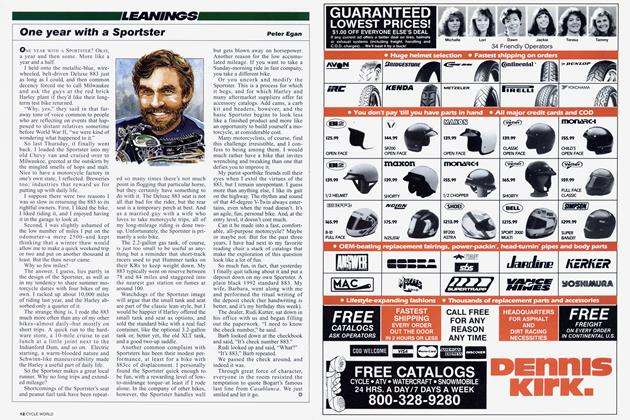

Parking lot at Assen

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

JUST GOT BACK FROM EUROPE ABOUT 1 a.m., after 10 days on the Cycle World Dutch GP Tour (extensive, carefully punctuated story to come). We rode from Munich to Assen, Holland, and back to Munich, then spent 27 hours in six airports getting home to Wisconsin, where our survival on the cab ride home from the Madison airport proved that my wife Barbara and I lead a charmed life and caimot be killed by normal bad luck.

Our cab driver may have been the most inept pilot of a self-propelled machine I have ever seen. Cold beads of terror-sweat rolled down my back like ball bearings, and when we finally lurched into the driveway I gave the driver a large tip, mostly as an offering to the gods for having spared our lives. Good to be home.

But it was good to be at Assen and riding in Europe again, too.

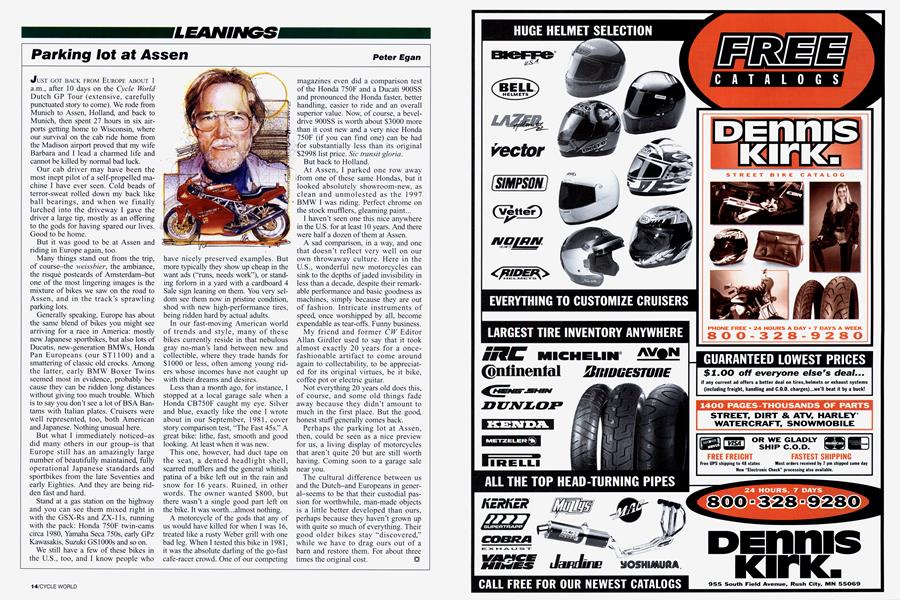

Many things stand out from the trip, of course-the weissbier, the ambiance, the risqué postcards of Amsterdam-but one of the most lingering images is the mixture of bikes we saw on the road to Assen, and in the track’s sprawling parking lots.

Generally speaking, Europe has about the same blend of bikes you might see arriving for a race in America: mostly new Japanese sportbikes, but also lots of Ducatis, new-generation BMWs, Honda Pan Europeans (our ST1100) and a smattering of classic old crocks. Among the latter, early BMW Boxer Twins seemed most in evidence, probably because they can be ridden long distances without giving too much trouble. Which is to say you don’t see a lot of BSA Bantams with Italian plates. Cruisers were well represented, too, both American and Japanese. Nothing unusual here.

But what I immediately noticed-as did many others in our group-is that Europe still has an amazingly large number of beautifully maintained, fully operational Japanese standards and sportbikes from the late Seventies and early Eighties. And they are being ridden fast and hard.

Stand at a gas station on the highway and you can see them mixed right in with the GSX-Rs and ZX-1 Is, running with the pack: Honda 750F twin-cams circa 1980, Yamaha Seca 750s, early GPz Kawasakis, Suzuki GS 1000s and so on.

We still have a few of these bikes in the U.S., too, and I know people who

have nicely preserved examples. But more typically they show up cheap in the want ads (“runs, needs work”), or standing forlorn in a yard with a cardboard 4 Sale sign leaning on them. You very seldom see them now in pristine condition, shod with new high-performance tires, being ridden hard by actual adults.

In our fast-moving American world of trends and style, many of these bikes currently reside in that nebulous gray no-man’s land between new and collectible, where they trade hands for $1000 or less, often among young riders whose incomes have not caught up with their dreams and desires.

Less than a month ago, for instance, I stopped at a local garage sale when a Honda CB750F caught my eye. Silver and blue, exactly like the one I wrote about in our September, 1981, cover story comparison test, “The Fast 45s.” A great bike: lithe, fast, smooth and good looking. At least when it was new.

This one, however, had duct tape on the seat, a dented headlight shell, scarred mufflers and the general whitish patina of a bike left out in the rain and snow for 16 years. Ruined, in other words. The owner wanted $800, but there wasn’t a single good part left on the bike. It was worth...almost nothing.

A motorcycle of the gods that any of us would have killed for when I was 16, treated like a rusty Weber grill with one bad leg. When I tested this bike in 1981, it was the absolute darling of the go-fast cafe-racer crowd. One of our competing

magazines even did a comparison test of the Honda 750F and a Ducati 900SS and pronounced the Honda faster, better handling, easier to ride and an overall superior value. Now, of course, a beveldrive 900SS is worth about $3000 more than it cost new and a very nice Honda 750F (if you can find one) can be had for substantially less than its original $2998 list price. Sic transit gloria.

But back to Holland.

At Assen, I parked one row away jfrom one of these same Hondas, but it looked absolutely showroom-new, as clean and unmolested as the 1997 BMW I was riding. Perfect chrome on the stock mufflers, gleaming paint...

I haven’t seen one this nice anywhere in the U.S. for at least 10 years. And there were half a dozen of them at Assen.

A sad comparison, in a way, and one that doesn’t reflect very well on our own throwaway culture. Here in the U.S., wonderful new motorcycles can sink to the depths of jaded invisibility in less than a decade, despite their remarkable performance and basic goodness as machines, simply because they are out of fashion. Intricate instruments of speed, once worshipped by all, become expendable as tear-offs. Funny business.

My friend and former CW Editor Allan Girdler used to say that it took almost exactly 20 years for a oncefashionable artifact to come around again to collectability, to be appreciated for its original virtues, be it bike, coffee pot or electric guitar.

Not everything 20 years old does this, of course, and some old things fade away because they didn’t amount to much in the first place. But the good, honest stuff generally comes back.

Perhaps the parking lot at Assen, then, could be seen as a nice preview for us, a living display of motorcycles that aren’t quite 20 but are still worth having. Coming soon to a garage sale near you.

The cultural difference between us and the Dutch-and Europeans in general-seems to be that their custodial passion for worthwhile, man-made objects is a little better developed than ours, perhaps because they haven’t grown up with quite so much of everything. Their good older bikes stay “discovered,” while we have to drag ours out of a barn and restore them. For about three times the original cost. □