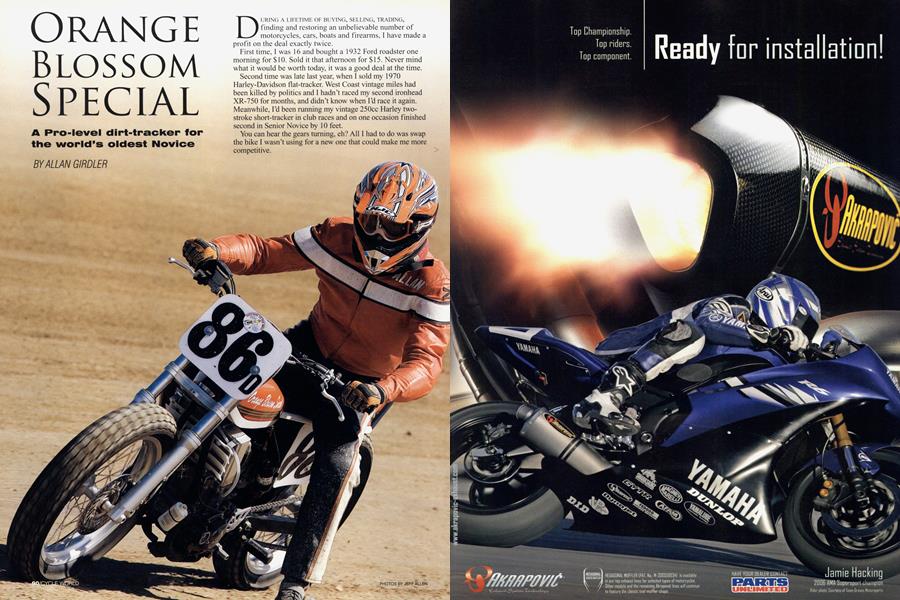

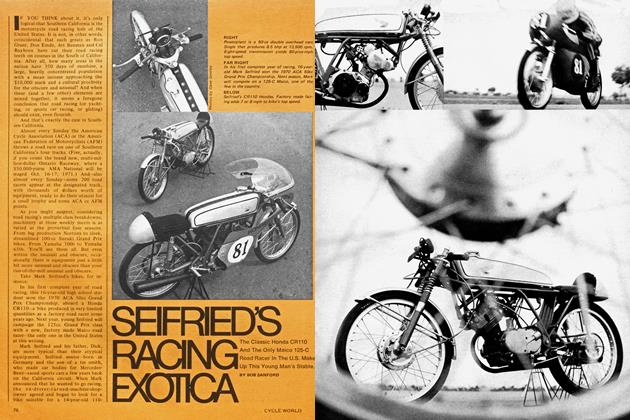

ORANGE BLOSSOM SPECIAL

A Pro-level dirt-tracker for the world's oldest Novice

ALLAN GIRDLER

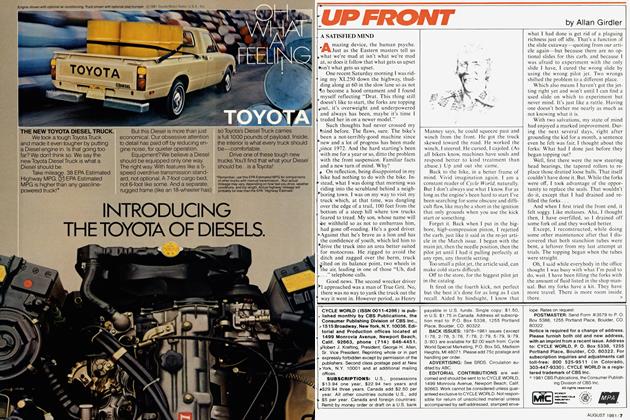

DURING A LIFETIME OF BUYING, SELLING, TRADING, finding and restoring an unbelievable number of motorcycles, cars, boats and firearms, I have made a profit on the deal exactly twice. First time, I was 16 and bought a 1932 Ford roadster one morning for $10. Sold it that afternoon for S15. Never mind what it would be worth today, it was a good deal at the time. Second time was late last year, when I sold my 1970 Harley-Davidson flat-tracker. West Coast vintage miles had been killed by politics and I hadn't raced my second ironhead XR-750 for months, and didn't know when I'd race it again. Meanwhile, I'd been running my vintage 250cc Harley twostroke short-tracker in club races and on one occasion finished second in Senior Novice by 10 feet. You can hear the gears turning, eh? All I had to do was swap the bike 1 wasn't using for a new one that could make me more competitive.

Here begins the math. My race XR came out of a burning barn, literally. I bought it for parts, paid $3500, but it was so good beneath the soot and grime 1 restored it instead. Most of the missing parts were already in my spares collection so the finished product cost $5000 total. 1 raced it for 10 years with no major repairs.

Nostalgia is better than ever these days. I checked the classifieds and set the sale price at $15,000, which I got from the first prospect, in cash-and yes, that means I left money on the table. But as with the classic '32 Ford, a tre-

mendous profit for no work or risk was enough for me. I mean, 10 years of free racing followed by triple the investment.

Flush with capital, it was time for a new bike. Which one? For professional help, I turned to Richard Pollack, a.k.a. Mule Motorcycles (www.nwleniotorcycles.net), whose work is often seen on these pages. Given my talent and our local tracks, I asked, what would be the best machine for me to do my best on?

Honda CRF450R, he said.

How about a Honda CR250R two-stroke?, I countered, same power and less weight.

Too hard to ride, he said.

What about a CRF250R, then? Four-stroke power but less weight than the 450 and it’s gotta be easier to ride.

It’s easier to learn to use the power you have, he said, than to need the power you don't have.

Fair enough. I went to the cheerful Honda store, a couple miles past the Honda store that grabs you by the lapels, and got them to roll out an ’05 CRF450R. This was just before the electric-start X model and I wanted to be sure I could start the 450 pedal ly. I could, so I bought it.

Next, some history.

When the AMA laid out the original rules for the current Grand National Championship, way back in 1934, the races were for stock bikes, as sold to the public. Then, as always happens in racing, they allowed modifications, then options and then full-on race machines, provided they could be bought in stores, and of course Indian and Harley-Davidson and Triumph and BSA and Norton and Matchless et al were

happy to sell you a racebike.

And then racing became so specialized, and the big makers so willing and able to swamp the little guys, that the engine became the motorcycle-you got a motor from the dealership and it came with a list of frame, suspension, bodywork, etc. suppliers and you built the thing yourself, or had someone do it for you.

Put more bluntly, starting 30-odd years ago, you couldn’t buy a dirt-track bike. You could get a motocrosser straight from the showroom, a production roadracer needed a couple of hours taking things off and taping things over, but dirt-trackers required special skill and knowledge...and the original, all-American form of racing has been in decline ever since (see sidebar, page 98). To the AMA’s credit, the race department created a semi-stock class. Take

a stock MXer, swap for 19-inch wheels and non-knob tires, lower the suspension and disable the front brake, and you have a DTX, legal for most amateur, club and even Pro dirttrack classes.

Sounded like the plan to me. My son John and I removed the CRF’s wheels and unlaced the rims from the hubs. The tires and rims went to the local dirtbike store, to be sold on consignment, and the hubs, via Mule Motorcycles, went to Buchanan Spoke & Rim, where they got stainless-steel spokes and 19-inch rims, over which went a set of Maxxis dirt-track tires.

We pulled the fork and rear shock and Mule had them shortened and revalved. With numbers attached, my DTX Honda was ready for action.

Well, almost. I couldn’t resist riding the bike up to where the post office leaves my mail and OMYGOSH what power! And so sudden. The light-switch analogy doesn't work here; try grabbing an electrode in each hand!

When I mentioned this to the fast guys in the club, they said motocross needs instant response but dirt-track prefers momentum, and there is a solution, a heavier flywheel from A&A Racing (www.aaracing.com), to me the best source for dirt-track stuff.

I got one, along with excellent instructions as to where to grind clearance for the larger rim and how to bevel the ignition wires so they won’t rub, and as predicted the new flywheel smoothes and soothes the power delivery.

Oh, and while I was on the phone with A&A, 1 got a set of folding rubber footpegs that swapped instantly with the steeltoothed motocross pegs, banned in dirt-track for good reason; ask me about putting one through my boot sometime.

At this point, I had paid $6500 for the CRF, plus off-road registration, plus $1100 for the modifications and parts, offset by the sale of the stock rims and tires. Call it $7500 for a club-legal machine, ready for short-track, TT. half-mile or even mile racing if 1 got the chance.

And at this point II, our club suspended operations, mostly because the one man willing to do all the work at

the races retired. At this point III, I realized that while the DTX'd CRF was viable and practical and eli gible and competitive, it wasn't what I really deep-down wanted. Plus I still had money in the bank, and what fun is that?

We live (thank goodness) in a free-market society, so while there has been a modest but steady demand for dirt-track frames, there has been a competitive number of suppliers.

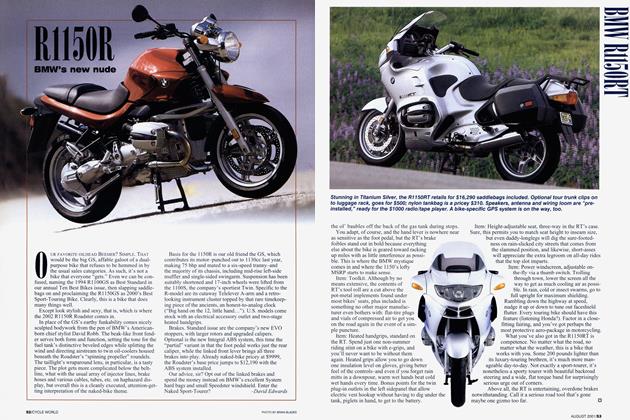

The one I know best is Ron Wood Racing, a couple blocks from CWs shops. Ron Wood the company is U.S. headquarters for Rotax, and Ron Wood the man is best known in history for building Nortons that sometimes outran the Harleys back when Norton was in business.

Wood cares more for the present. He designed a competitive frame and rear suspension for the Rotax Singles, and when the big guys got into the four-stroke single-cylinder act, Wood came out with kits for the Yamaha and Honda

450s. You provide the engine and he supplies a frame, swingarm, shock, seat, tank, rear fender, radiator, engine mounts and hardware to fit the engine to the new parts, all for a few dollars less than $5000.

But wait, there’s more.

Wood and C&J and J&M (the other major frame-makers

and sorry if anyone’s left out) assume that when you build a “framer,” as the racers say, rather than a “motocrosser,” inside talk for a DTX’d bike, you will use aftermarket wheels and quick-change hubs and brakes and bars and so forth.

All that equipment is extra, and expensive. Luckily, most of it I already had. There was no way, though, I could use the Honda shock or the leading-axle fork. Instead, I sold the reworked suspension components, for only a bit less than I’d paid to have them reworked, and I sold or swapped the stock Honda radiators, shrouds, frame and swingarm and airbox, all the stuff I couldn’t use.

Here’s the professional help. I got a set of Yamaha R6 fork tubes, with much softer springs. Southland Racing has the triple-clamps to go between the Wood steering head and Yamaha tubes, which as you may notice have had the unneeded bosses removed and the sliders smoothed out and polished.

Pollack’s day job is building the bits that rocket scientists shoot into space, no kidding. He says he’s a fabricator, that any part can be attached to any other part and that his job is to make the part that goes between the other two parts.

Which he did witness the sculptured block between the Yamaha fork leg and the Honda brake carrier, and the block

between the Wood swingarm and the Honda rear brake, and the little tabs for the Honda master cylinder on the Wood frame, and the hanger for the high Honda pipe, and the spacers to use the Wood axle and blocks with the Honda hub.

Lots of work and time and talent and yup, money. But I had three of the four and Pollack has the talent, and I kept the Honda handlebars and throttle and cables and grips and carb and wiring and black box, while Roy the bodyshop guy knew someone who could swivel the radiator pipe to clear the exhaust header. Building a motorcycle like this is a fine way to appreciate how much work and thought goes into the stock bike.

The other precaution was, when I got the Wood kit, I primed the steel parts and put the engine into the fame, bolted on the swingarm, left the assembly with Pollock for the machine work and fabrication, then put the entire bike together and ran it for a few laps, just to be sure everything went together before we did the paint and polish.

Yes, we did need to make some adjustments, meaning the rehearsal paid off.

Everything was taken apart again, and powdercoated or painted and then put back together.

The paint job?

When I was a little kid, my folks would go into town from the family orange grove on Florida’s east coast, and if I was lucky we’d be there in time to admire the crack passenger trains-this was back when trains were the only way to travel. My favorite was (you guessed) the Orange Blossom Special, an admiration shared by bluegrass stars Flatt & Scruggs, witness their song by that title.

That family grove disappeared beneath the wheels of progress two generations ago, but now we live on our grove in California, and my wife went online and found a postcard illustrating that train. I took that and the bike to Uptown Cycle Design in San Diego and they did the Art Deco scheme seen here. Sharp, eh? Almost too good to ride.

But that won’t stop me. The project, as seen here, weighs 221 pounds with water and oil, but no gas, 9 pounds lighter than the DTX version and 8 pounds less than a stock CRF. Seat height is 31 inches, 6 inches lower than the motocrosser’s. Total cost? A good S15K, give or take.

The club is re-forming at this writing and soon as possible we’ll see if money will make up for lack of talent.

My bet is, I may never be fast but I will be faster. □