ON THE TRAIL OF THE PHANTOM DUCK

From the Barstow Barrens, To the Lights of Vegas, This land belongs to you and me.*

Allan Girdler

*Thanks, Woody, we needed that.

WHEN THIS ADVENTURE began, the true identity of the Phantom Duck of the Desert was a mystery. So it remained through the Phantom Duck unorganized Barstow-to-Vegas Memorial Trail Ride, and so it is now.

Desert guys say the Duck has been around for years. He does exist, therefore, and tracking down the man behind the pseudonym should be easy for a keen investigative reporter. The investigation has not taken place. Nor will it. Years ago an older hand came through with the exact bit of advice needed for this situation.

There’s such a thing, he said, as researching a story too far.

The history of the actual ride is well known. In 1968 one of the desert racing clubs organized a point-to-point race. Barstow, California, to Las Vegas, Nevada. The terrain between those two cities is what Californians call the High Desert. It contains granite crags, dry lakes of soda, mud and talcum, alkali flats, mountain passes, cactus, ravines, sand washes and every hazard known to outdoors man. Great place for a race. Better, bisecting this area and connecting the two cities is a string-straight Interstate highway, ideal for gas stops, checkpoints and hiking to after the bike falls apart.

Barstow-to-Vegas became the prime event for off-road riders. Hundreds, then thousands of racers showed up every year.

Concurrent with this there developed a social issue. In every society, a group of people exists whose self-appointed task it is to find out what the common folks are doing . . . and make them stop.

When leisure and travel and outdoor recreation were the province of the few, there was no problem. But when prosperity freed great numbers of people to roam this great country at their own whim, we suddenly learned there wasn't enough wilderness to go around. All those folks were clogging the highways, jamming the parks and tearing up the desert.

The few who believe the many should know their place and stay there, are not stupid. They play the media better than Earl Scruggs plays the banjo. They know government procedure better than Billie Jean King knows tennis. So it came to pass that using the publicly owned desert became a crime against nature. Putting on a race became a matter of filling out forms and having meetings and in general trying to find the combination while the other side changed the locks.

In every society, a group of people exists whose selfappointed task it is to find out what the common folks are doing . . . and make them stop.

(Does this sound too strong? Weeks before this non-event, a desert race in Arizona was canceled because there had been no environmental impact report filed for the land in question. The land in question is an Air Force bombing range. The prosecution rests.)

In any event, the 1974 Barstow-to-Vegas drew 3000 riders. In 1975 the Bureau of Land Management denied permission to have the race, or any race at all.

The opposition was delighted. The racers were disheartened. The only choice seemed to be lay low and race elsewhere. Make a fuss and we’ll get landed on all the harder, i.e. let the little psycho have Poland and he won’t invade France.

Comes now the Phantom Duck. The area in question was in no sense a wilderness. The Spanish Army used to have a trail through the place. The land is crossed and criss-crossed with powerline roads, pipeline service roads, farm roads, mine roads and mines for turquoise, talcum and various exotic minerals.

The BLM doesn’t object to roads and trails. It’s people they can’t stand. Further, the area was already designated for offroad use on the trails. The objections and restrictions applied to organized and sanctioned events.

A key point. Letters appeared in the enthusiast press. Operating, as he said, out of a post office box “in a city not my own” the Phantom Duck announced that on the anniversary of the Barstow-to-Vegas Race, he planned to ride from—Yes!—Barstow to Vegas. He would use only designated open dirt roads and trails. He had arranged for permission to cross private land when needed. He would leave the approximate location of the old race starting line at 8 a.m. on that particular Saturday and intended to ride, completely within the law, to the approximate finish line. His ETA was before dark, there were various places along the way which would make fine gas stops if anybody was so inclined. The announcement was explicitly made that this event was not an event, was not and would not be orgánized. Still, the implication was that the Duck would not mind some company.

The BLM doesn't object to roads and trails. It's people they can't stand.

Call it a Memorial, call it a Political Protest, call it almost anything, the reaction on my part was that this was a man worthy of admiration. This was the sort of man one could follow to, well, to Las Vegas. It is, of course, possible that the Phantom Duck is in actuality a real estate man, whose secret desire is to lure the gullible past Windswept Estates. He could be western sales rep for a thermal underwear factory. He could even be an undercover BLM agent, a lackey of the running dog preservationists, plotting to lure us trusting bikers into committing indiscretions while the TV cameras recorded all.

Better we not know. Better not research the story too far. Instead, there arose the gleeful hope that after years of watching political protests, yr. biased reporter might for once get to be in one. Actually take part in our democratic process, so to speak.

Validation of a political protest requires a manifesto, a declaration of some sort.

To wit. Painting with the broadest brush, it’s my opinion that off-road riding and off-road racing, indeed any form of vehicular recreation on public lands, is getting the pointed end of the stick.

There are people who don’t like motorcycles. There are people who don’t like the public. There are people willing to do anything required to land on the trendy side of any given issue. These people have found the perfect target—us. An exquisite selection of words and phrases are drummed at the public from every quarter. We are told about the rape of the land and soon any modification to Mother Earth is a despoilation unequaled since the library at Alexandria was burned by whoever it was that burned it.

The thing boils down to values. The new Civic Center Complex is hailed as the rebirth of downtown, never mind that to my eye governmental buildings are sterile> wastelands. A tire track on the desert becomes (shudder) a Scar. If you truly love nature, dammit, even the Golden Gate Bridge is a scar.

They have taken the issue away from us. More precisely, the actual issue hasn’t been discussed. All public debate on the subject of land use has begun from the position that preservation is always a virtue. Total preservation is impossible, but nobody gets to talk about that.

If you truly love nature, dammit, even the Golden Gate Bridge is a scar.

If the debate begins with the tacit assumption that we must preserve everything, which it has to date, then we are backed into a choice of two poor stands. Either we play what I’d term Uncle TwoStroke, waiting at the kitchen door of the power structure for scraps of permission, or we blindly deny the obvious, namely that when you ride motorcycles across dirt you’re gonna leave marks.

Off-road motorcycling will be more effective as a political force only when we take our own side, fight our own war.

Anyway, (he wrote as he began to get red in the face, wave his arms about and coin slogans like “Power to the Pentons!”) it struck me it was time to come out of the motorcycle park. We who ride the desert are part of the public too, and we expect to have some share in the public land. Give us fair guidelines and we’ll abide by them.

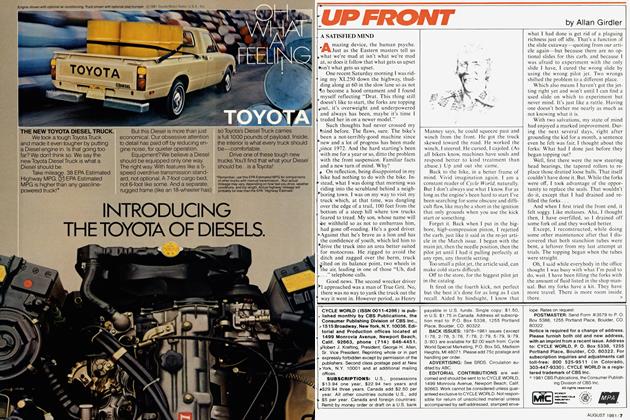

We went prepared, we being myself, retired desert racer Chuck Johnson, van driver/caterer Henry Manney and photographer Lynn Girdler. Because we recognized the possibility of official scrutiny, that is, BLM or rangers prepared to be sure we were legally equipped, we took a Honda XL250 and an ex-ISDT Triumph 500, both with full road equipment right down to rear-view mirrors, drivers’ licenses and insurance cards.

Make that almost prepared. The night before the start, the high desert was hit by a Blue Norther, 50-mph winds and below freezing temperatures. The route lead roughly north, so naturally the wind was out of the north, for a chill factor of about zero degrees. We had an ice chest filled with refreshments. My woolies were at home in the closet.

Arriving at the starting line 15 minutes before the Duck was scheduled to leave, we learned the ride was in fact not organized. Some people had left already, the Duck among them. Some people were just pulling in.

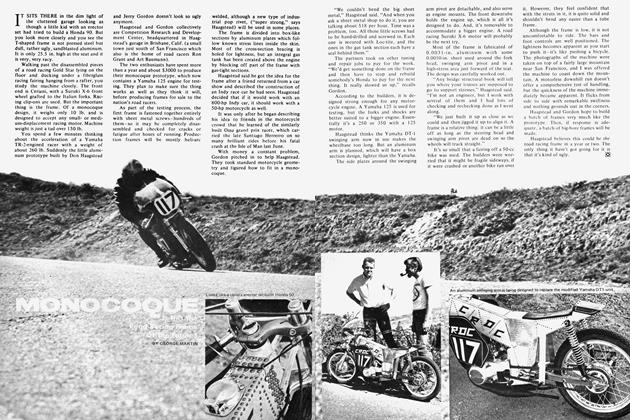

The riders were an assortment. Old and young, male and female, towering fullrace desert bikes, another ISDT Triumph, couple new Thumpers and flocks of old Ossas, Yamaha, Huskies, early DTs with license plates, even a mini-cycle or two. This w'as not a race.

Numbers? Hard to say. We never saw more than 20 bikes at one time, which led Henry to estimate 50 total. One of the newspaper guys said later he figured there were 150 people actually riding. That may be, as riders were still pulling in after we left. More showed up to start riding at the first gas stop and on the way home many hours later we saw lone lights hobbling across the desert.

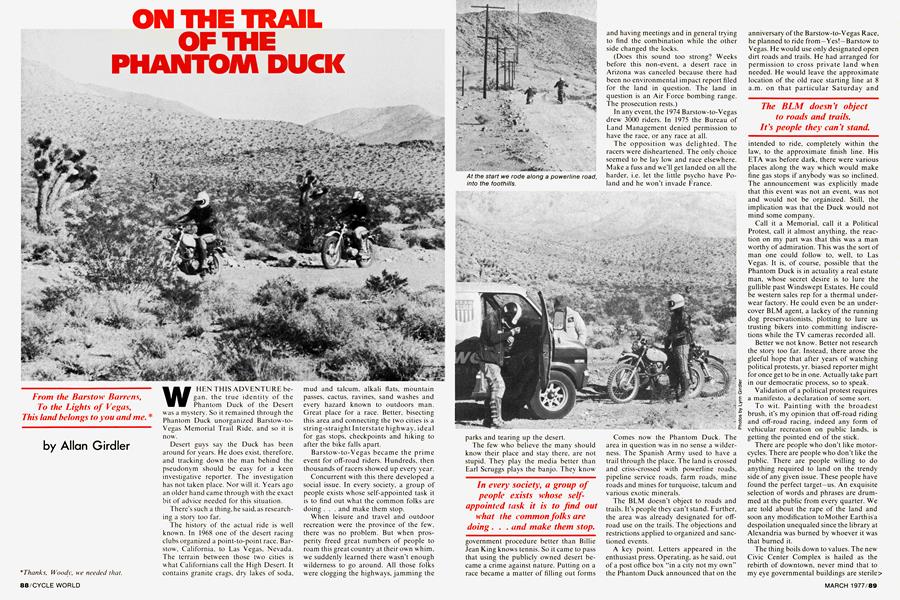

There being no ceremony. Chuck and I raided the suitcases for every stitch of clothing we could pull on, fired up and headed north along a powerline road punctuated by square cross-grain ditches.

A turn-by-turn description of somebody else’s trail ride is pretty much like hearing your mother-in-law replay the previous evening’s bridge game, so the day will be compressed.

li e who ride the desert are part of the public too, and we expect to have some share in the public land. Give us fair guidelines and we 'll abide by them.

We began at 8 a.m. and rode until 4 p.m. for an odometer reading of 140 miles. We danced all day. We did the Hardrock Hop, the Whoop-De Watusi, the Sand Wash Shuffle and the Flat Lake Flyer. We rode on mining roads. Jeep trails, in ravines, across dry lakes and over one mountain range.

The dam has busted and the crazies have escaped!

Several incidents stand out.

The trail followed a sand wash beneath the Interstate. I wish I could have seen the looks on the faces of those poor wretches droning across the pavement in their little boxes when 25 dirt bikes caroomed from under the highway and went leaping and jumping over the gullies and onto the dry lake. The dam has busted and the crazies have escaped!

On our way to the mountain pass. Chuck remarked that during the actual races the course led down a dry waterfall. Chuck was wrong. It wasn’t dry.

It was frozen.

At the top of the pass there’s a spring, the water from which has eroded a narrow gorge down the mountain. Five feet wide, 20 feet below the rest of the ground. The gorge was littered with parts torn from four-wheel vehicles foolish enough to tackle it. You’d pick a gap between two boulders, drop two feet and land on the ice. Wow.

When we left the biggest mountain, we rode onto a dry lake comprised of talcum powder. Right, the stuff you put on babies. Raw talcum is as soft as the finished product, as smooth and as absorbent. Only difference visible is that the raw' talcum is brown.

Uncanny. The lake was perfectly flat, perfectly smooth. The powder absorbs all vibrations and most of the noise. Because the lake is five miles or so wide, there are no close reference points.

My inner ear knew' I was moving while eyes and fingertips had the impression of standing still. Like a dream, literally, a sensation of floating suspended, of riding across an endless bowl of butterscotch pudding.

As the sun sank in the west, we became very lost. We were 15 miles past the last lime marking and cruising along with the Interstate in sight when Chuck flashed on a hill. That, he said, is w'here the finish line used to be. So we veered over there, and there it was.

In the political sense, we lost. Where 3000 motorcycles once rode, there were 150. In terms of protest, nobody knew we were there.

But oh, what a beautiful day it was. On the way home somebody said something about next year and I, whose feet were still numb said, “No Way!” I spent the w'hole day being cold, scared or both. Once is enough.

“In a week.” Lynn said, “you’ll have forgotten the bad parts.”

And I have. Thanks, Phantom Duck, whoever you are.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue