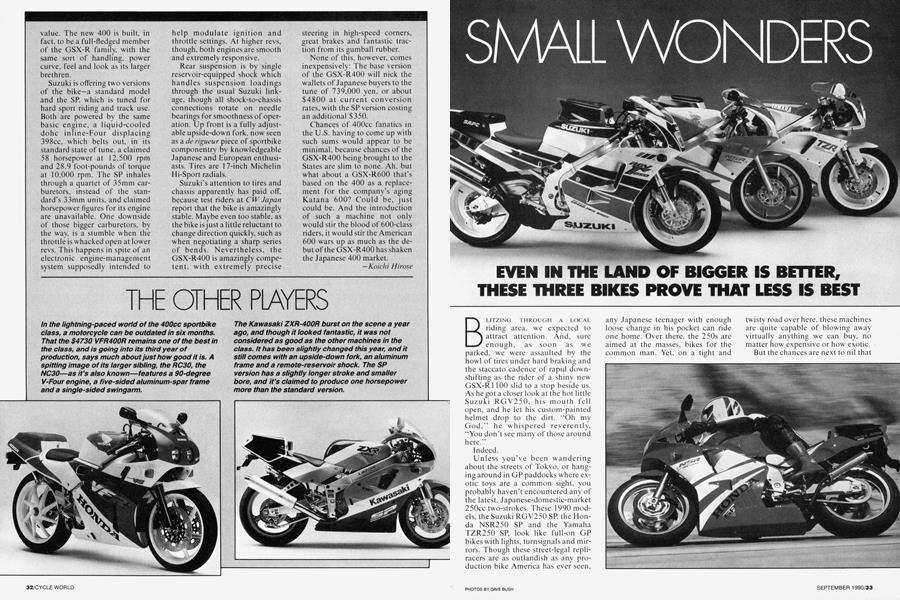

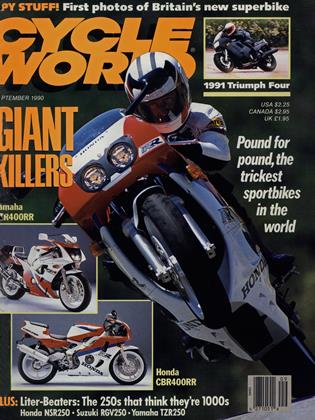

SMALL WONDERS

EVEN IN THE LAND OF BIGGER IS BETTER, THESE THREE BIKES PROVE THAT LESS IS BEST

BLITZING THROUGH A LOCAL riding area, we expected to attract attention. And, sure enough, as soon as we parked, we were assaulted by the howl of tires under hard braking and the staccato cadence of rapid downshifting as the rider of a shiny new GSX-R 1 100 slid to a stop beside us. As he got a closer look at the hot little Suzuki RGV250, his mouth fell open, and he let his custom-painted helmet drop to the dirt. “Oh my God,” he whispered reverently, “You don’t see many of those around here.’’

Indeed.

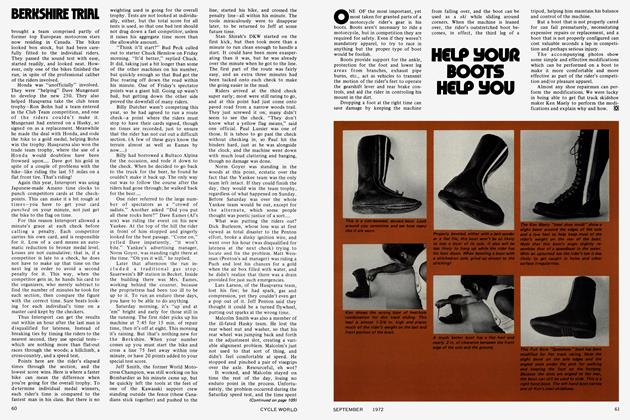

Unless you’ve been wandering about the streets of Tokyo, or hanging around in GP paddocks where exotic toys are a common sight, you probably haven’t encountered any of the latest, Japanese-domestic-market 250cc two-strokes. These 1990 models, the Suzuki RGV250 SP, the Honda NSR250 SP and the Yamaha TZR250 SP, look like full-on GP bikes with lights, turnsignals and mirrors. Though these street-legal repliracers are as outlandish as any production bike America has ever seen. any Japanese teenager with enough loose change in his pocket can ride one home. Over there, the 250s are aimed at the masses, bikes for the common man. Yet, on a tight and

twisty road over here, these machines are quite capable of blowing away virtually anything we can buy, no matter how expensive or how exotic.

But the chances are next to nil that Zwe will ever see any of these 250s for sale in America. First of all, there are the EPA problems in homologating a two-stroke for the street. Then, in terms of dollar-per-cubic-centimeter, they’re too expensive for American tastes. Most riders here still believe in the dictum that horsepower rules, that nothing can beat cubic inches. And that's their loss. Believe us, we have nothing at all against gobs of horsepower, it’s just that these 250s have a lot to offer. Their performance levels are exciting, and they are as agile as hummingbirds on diet pills, helped by weights between 322 and 343 pounds. Also, time spent on one is excellent training for riders who want to improve their riding technique, because riding a 250 fast stresses finesse over brute force. But broad generalizations about these 250s tend to be unfair, because few classes offer so much diversity, so much individuality, among the key players. The Suzuki and the Honda, for example, each use liquid-cooled, V-Twin engines, while the TZR’s liquid-cooled parallel-Twin has its cylinders mounted backwards, with the carbs in front and the exhaust pipes pointing straight back, exiting from under the seat and poking out through the tail section. All three are screamers, but they scream at different pitches. The Yamaha and the Suzuki rev to 1 1,500 rpm, and the Honda goes up to 12,000. You need every one of those revs to make these machines work, too. The Yamaha has a tall first gear and the most peaky of the engines, with nothing much happening below 8000 rpm. The Suzuki has a bit wider powerband, picking up momentum around 6000 rpm. But it’s the Honda with the broadest power delivery of all, smoothly pulling from as low as 5000 rpm. All three use dry clutches and six-speed transmissions.

But the frames and suspensions on the 250s are the most interesting. Each frame is crafted from aluminum, no steel allowed, and each is a testament to the latest technology borrowed from the racetrack. The Yamaha starts with an upside-down fork, mated to a Deltabox frame. Deceptively simple in design, the largebeam frame is strong and light, though its braced swingarm appears delicate compared to the sizable units on the other two machines.

The Suzuki’s swingarm looks like it was stolen from Kevin Schwantz’s RGV500 GP bike. The right side has a large banana bend to give the twin exhaust pipes enough clearance so that both can exit on the right. The left side of the arm is more conventional in appearance. The rest of the frame looks similar to the Yamaha’s except that the Suzuki uses two bolton lower frame rails that cradle the engine. The RGV250 also uses an upside-down fork.

Like the Suzuki, the Honda uses a “bent” swingarm, though it routes its pipes to both sides of the machine. Overall, the Honda has clean, crisp styling, and is a joy to look at whether from afar or up close.

If you’re wondering if all this trickery and expensive engineering is worth the effort and cost, the answer is yes. Lighter than the 400s, and with chassis every bit as competent, the 250s corner with the kind of pinpoint precision that larger motor-cycles just can't approach, though straights of any length relegate the little bikes to the back of the pack.

Getting through corners quickly on a 250 takes a lot more skill than on a larger four-stroke machine, but once a rider becomes familiar with the demands of a 250, the bike rewards him with outrageous cornering speeds. Every move the rider makes translates into machine movement, so body position is crucial before entering the corner. Also, before diving into a turn, the rider must have the engine spinning near redline in order to get a good drive coming out. These bikes have a 45-horsepower limit, with most of that power above 10,000 rpm. so they are easy to bog, and lose momentum quickly.

Certainly, these 250s are not motorcycles that every American rider will lust after. But for the enthusiast who wants the ultimate sportbike, these are viable alternatives to the machines we currently have. Is, for example, an RGV250 SP a better sportbike than, say, a GSX-R1 100? In many ways it is, especially if you measure performance in terms of the whole ride and not just in terms of acceleration between corners. And someday, if American riders begin to evaluate a motorcycle on its overall performance instead of on its displacement, we just may begin to see these kinds of motorcycles stateside. Until then, though, not many of us will be able to take a ride on one of the super 250s. And, as we’ll testify, it’s an experience worth looking forward to. —Camron E. Bussard

Honda NSR250

$4959

Suzuki RGV250

$4614

Yamaha TZR250

$4959

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontFathers, Sons And Motorcycles

SEPTEMBER 1990 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeOut In the Midday Sun

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Discriminating Cheapskate

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersDinin' Dressers

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupConquest Goes Polish

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Euro-News: Diesels And Better Beemers

SEPTEMBER 1990